What’s happening to Japan’s economy?

Stay up to date:

ASEAN

Japanese GDP contracted at an annualized rate of 1.6% in the second quarter, providing another strong hint that all might not be going smoothly for Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s plan to revive the country’s sluggish economy.

What happened in the second quarter?

The data suggests that this latest bout of weakness has been driven by a slump in private-sector demand and net trade.

That’s bad news, as it suggests two of the channels through which Abenomics – the Japanese government’s ambitious growth plan that includes the “three arrows” (fiscal stimulus, monetary stimulus and structural reforms) – is supposed to feed into the real economy. That is, the large-scale asset purchases by the Bank of Japan has weakened the yen, which should have provided a boost to exports while fiscal stimulus and reforms should have helped boost Japanese workers’ wages.

So what’s holding the economy back?

Firstly, the slowdown in China is taking its toll on its neighbour’s economic prospects.

As one of the key drivers of global demand in recent years, China’s slowdown is having spillover effects on the global economy, with Japan’s export sector far from immune. The worsening outlook also appears to have affected business investment, which disappointed again in the second quarter.

Perhaps more worrying, however, is that despite strong encouragement from the government, real wage growth (the growth in incomes adjusted for the rate of inflation) has failed to see a sustained pick-up. In fact, earlier promising signs of growth appear to have reversed, with real wages falling 2.9% year-on-year in June, the fastest pace of decline in seven months.

Moreover, falling unemployment in the country has so far been insufficient to offset drops in the total number of people in work, as Japan’s worsening demographics mean that there is a growing number of retirees as a share of the total population. That is holding back the impact that real wage growth is likely to have on consumer spending.

These factors, along with the increase in sales tax last April, are helping to restrain household demand despite significant pushes by the authorities to get companies to increase wages. In fact, there are growing voices within Japan calling for the government to intervene once again in this year’s pay negotiations in order to prompt firms to push pay growth higher.

So what can Abenomics’ “third arrow” do to support Japan’s growth prospects?

One of the big factors that Japan will have to face is the inexorable decline of its workforce. Under the IMF’s “negative” scenario, the labour force is expected to decline from 66.3 million in 2010 to 56.8 million in 2030.

Although the problem is a significant one, there are a number of reform options open to Japanese policy-makers in order to offset its effects.

- Increasing labour-force participation – especially among women.

Japan has a relatively low level of female labour-force participation compared with its developed-market peers. This means that there are lots of potentially highly productive workers being kept out of employment at a time when the total number of workers is already in decline.

The authorities are already seeking to address this issue by increasing the provision of childcare, but a recent IMF working paper suggested that they could also look at removing distortions in the tax system that prevent women from joining the labour force on a full-time basis.

- Lower barriers to entry for migrants.

One of Japan’s most acute problems is an inability to find workers to fill current vacancies. Although increasing the participation rate will go some way towards addressing this issue, it is already struggling to offset long-term declines in the total workforce, as illustrated above.

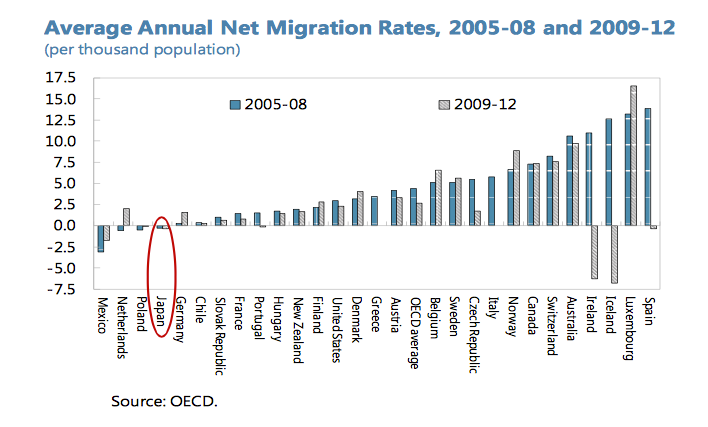

Higher immigration could provide an answer to this problem. Unfortunately, Japan currently has the second-lowest immigration rate of OECD countries:

While the authorities have brought in measures to allow higher numbers of skilled migrants into the country, this is unlikely to be sufficient to plug the widening labour gap. The IMF paper suggests that to fill the country’s sector-specific vacancy gaps they could introduce guest-worker programmes, and loosen entry requirements in sectors with labour shortages.

- Increase investment in capital-intensive technologies and machinery.

With the fiscal space being provided by the Bank of Japan’s massive asset-purchase programme, the government could launch an ambitious investment drive into cutting-edge technology in order to boost productivity.

In effect, the government would be shifting away from the helicopter-style fiscal stimulus (effectively pumping money through existing channels to increase demand) towards a more targeted model that aims to boost the output of its workers. If successful, it could allow the workforce to maintain or even increase levels of production, even as the total number of working people falls.

Have you read?

How will Japan shape Asia’s future?

How can we improve gender equality in Japan?

Can Abenomics revive Japan’s economy?

Author: Tomas Hirst is editorial director and co-founder of Pieria magazine and was previously commissioning editor, digital content at the World Economic Forum.

Image: Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe attends a news conference at his official residence in Tokyo November 18, 2014. REUTERS/Toru Hanai

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Dave Neiswander

April 28, 2025

Alem Tedeneke

April 25, 2025

Michael Eisenberg and Francesco Starace

April 25, 2025

John Letzing

April 25, 2025

Luis Antonio Ramirez Garcia

April 24, 2025

Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas

April 23, 2025