4 key challenges for the global economy this autumn

Summer is over. Geopolitical risks will be the dominant theme this autumn. Image: REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

European Union

Summer will soon be over; autumn is coming. The global economy and financial markets will have to face some of the gathering political storm clouds.

While the global economy is weak, the macroeconomic risk assessment is more balanced than it has been for some time. At the same time, however, political risks have become more pronounced.

In America, Donald Trump has stirred angry voters in a bitter presidential election; in Europe, rising populism, increased security risks and the ongoing refugee crisis is setting the tone; in Ukraine, there is a risk that Putin will escalate conflict ahead of Russia’s parliamentary election in September; in China, a difficult political situation could pose long-term uncertainty for Asia; globally, turbulent oil prices are returning to centre stage. Political risks will dominate the autumn and the winter is getting closer: it is time to get ready.

US: Presidential elections changing the tone of politics

The US political system will not be the same after the presidential election in November. Even if Hillary Clinton becomes the next president, Donald Trump will have changed the tone of the political debate and the anger among the voters that have pushed Trump to the frontline will not dissipate if he loses the election.

Market reactions to the political uncertainty in the USA have, so far, been muted. The most likely outcome is a Clinton administration (market research seems to be in the neighbourhood of 60% probability for Clinton and 40% for Trump) that would continue with the basic policies from the previous Obama administration.

You could even argue that a Clinton administration potentially could be an improvement in terms of economic policy. If Hillary Clinton chose to echo the policies of Bill Clinton’s administration rather than those of Barack Obama, the US government might be somewhat more pragmatic in economic terms; that is to say, more fiscally conservative and less prone to regulatory interference in the business sector. Obviously, there is a risk that Bernie Sanders supporters will push the Democrats further to the Left, but on the other hand, the temptation to gain voters from former Republicans who shunned Trump could nudge Democrats towards the centre ground.

Even if Clinton holds a comfortable lead at the moment, the election campaign could still change its course. A major potential game-changer is the televised debates between the candidates, that will start on September 26th and continue in October, on the 9th and 19th. The Republican Party primary showed that Trump was able to use TV debates very efficiently. It is very difficult to meet a challenger who is as careless with facts as Trump. The Democrats seems to think that Clinton can meet Trump with a cool, calm attitude and avoid appealing to the lowest common denominator. However, for a candidate with negative ratings like Clinton, this is difficult. There is a clear risk that she will come across as an arrogant and cold establishment politician in a confrontation with Trump. It is always difficult to foresee the dynamic between two candidates before they have actually crossed swords. TV debates are potential game changers and it will be difficult to call the election results before we know how well Clinton can handle Trump.

Trump is arguing for large tax cuts that would increase the deficit in the short term. According to the Congressional Budget Office, Trump’s tax plan implies that the federal government’s deficit would increase from 75% of GDP in 2016 to 125% of GDP in 2026. A more expansionary fiscal policy would increase demand in the short term, which would imply higher inflation expectation, rising bond rates and a stronger dollar. On the other hand, a victory for Trump would also reduce migration, increase trade barriers and increase the risk of escalating trade wars. This would undermine the competitiveness and long-term growth of the US economy, which would imply a weaker dollar.

The most likely outcome is that Trump would create a great deal of media attention, but achieve very little in terms of concrete policy. The parallel that comes to mind is Silvio Berlusconi. This suggests that the US political system would remain in the same political gridlock that we have seen over the last decade.

Given that the fiscal position in the US has improved, and that a recovery phase is less demanding in terms of the need for political leadership, financial markets seem to be largely ignoring the presidential election in the US. The market risk from an increased probability for a Trump victory is likely to be a somewhat higher interest rate, wider credit spreads and somewhat stronger stock market and dollar appreciation. For global markets, Trump is negative for equities and bonds, because of the increased geopolitical uncertainty, and is strongly negative for Emerging Market Countries’ assets, and in particular for Latin America.

Europe: Terrorism, refugees and a changed political landscape

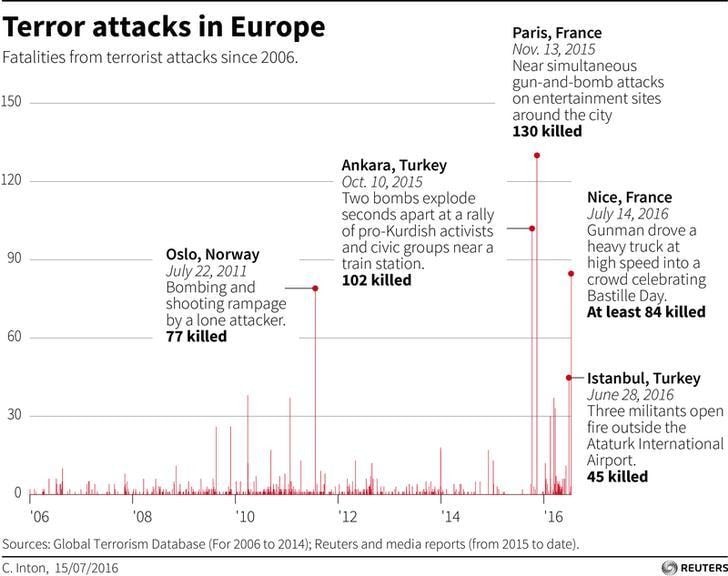

The security situation in Europe has become more problematic over the summer. The government in Iraq has made progress against ISIS, in cooperation with Kurdish forces and with strong international support. It seems that the fight against ISIS is now conducted along the same strategy that defeated the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001-2002 and removed Al-Qaida from Iraq in 2007-2008. This success involved local military and militia supported by imbedded US Special Forces, with heavy support from air strikes. The problem is that even if ISIS is pushed out of Mosul and Raqqa, the ideology will not have been defeated and ISIS will still be able to perpetrate large-scale terror attacks in Iraq and elsewhere.

The core difficulty is that the same set of circumstances that created ISIS will remain in place in the Middle East and North Africa for the foreseeable future. The kleptocratic and authoritarian governments of the region lay the foundations for weak state structures that are ill-equipped for modernisation. The legacy of violence from previous conflicts, in combination with populations divided along ethnic and religious lines, creates societies with a very low trust level.

There is little hope of reform for the region’s crony capitalist system, based on privileges for the few close to the authoritarian leader, and barriers to trade for normal entrepreneurs. This is a legacy stemming from both the Ottoman Empire and the post-colonial socialistic ambitions of the 1960s and 1970s. Therefore, economic prospects for the 500 million citizens in the Middle East and North Africa will remain lacklustre. A young population - in most of the region 60-70% of the population is below the age of 25 - adds to the dynamic. Without rapid job creation, the number of unemployed will increase.

The radicalisation of Islam, with a mixed origin from the Muslim brotherhood, Wahhabi ambitions to win proselytes, and the heritage from Al-Qaida, will not go away even if ISIS is pushed back.

It is likely that the organisation will concentrate on destabilising Iraq via sectarian violence, and continuing to fuel conflicts in North Africa. The security situation in Europe will remain very problematic. According to intelligence sources in Europe, ISIS might have as many as 200-300 potential terrorists in Europe. In addition, there is a risk that other unstable individuals will gain inspiration to commit acts of terror. The threat level in Europe and other advanced economies will not improve in the near future and a military defeat of ISIS and Iraq and Syria could even lead to an increased risk level in other regions.

The combination of the increased security threats and the migration crisis is rewriting the political manuscript of Europe.

A side-effect of the conflict in Syria and Iraq has been a rapid increase of migration to Europe. UN estimates indicate that over one million people have entered Europe with the intention of claiming asylum during 2015. The number of refugees coming to Europe is most likely going to be lower in 2016, but will remain much higher than the long-term average both this year and next. It should be pointed out that some four million refugees from the conflict in Syria and Iraq remain in the neighbouring countries (in Turkey 2.2 million, in Lebanon 1.1 million and in Jordan 650,000 people).

Germany, Sweden, Hungary, Austria and Italy have been the most affected countries in Europe (Hungary and Sweden with the highest per capita numbers, and Germany with the highest number in absolute terms). The inflows have decreased, at least partly due to the fact that the European Union has made a broader political agreement with Turkey and the Balkan route has been closed.

Nevertheless, the refugee crisis has altered the political landscape. Support for Right-wing populist groups has increased in many countries, not least in Germany and France, where terrible terror attacks in spring and summer reinforced this sentiment. After Paris, Brussels, Nice and Munich, it is also clear that, even with a radical increase in the efforts from the security forces, ISIS is still capable of operating in Europe. In most European countries, at least according to the EU Commission’s value surveys, migration is now a dominant political issue.

The rise of both Right-wing and Left-wing populism means that economic policy will be more complicated. The traditional social democratic parties that have historically dominated many European countries are going through a deep crisis, while populist Left-wing movements have seen increased support. In the UK, Jeremy Corbyn’s takeover of the Labour party reflects this trend.

The struggles of centre-Left governments in Italy and France to make moderate improvements to labour market flexibility indicate the consequences. Recent political developments have sapped the appetite for reform and cemented the political and economic stagnation that we have seen in Europe over the last decade. The problem is that Europe could get stuck in a negative circle whereby the lack of structural reforms leads to low growth, weak real wage increases and high unemployment, which in turn fuels discontent, giving even more energy to populism.

Russia’s power paradox

Russia and the Euro-Asian region have been strongly impacted by the reduction of energy and commodity prices. The conflict in Ukraine, and Russia’s aggressive stance against some of its neighbours, have also hit economic confidence hard. Economic activity contracted by almost 4% in 2015, and GDP will fall with another 1% during 2016. There are, however, signs that the economy might have passed through the worst period. The stock market has rebounded and the Rouble is trading somewhat above 60 against the dollar. Inflation peaked at 15% in 2015 and is now close to 7%.

Fiscal policy is not a major problem for Russia. The deficit will increase to 4% of GDP in 2016, but will then return towards balance going forward. The Russian government has already implemented fiscal measures and has a credible medium-term framework. The low level of debt, below 20% of GDP, is adding credibility. The current account is heading towards a surplus 5% of GDP during 2016. The labour market is flexible and unemployment has remained stable at around 6% during the crisis. The economic policy framework has been a source of credibility.

Russia could be heading towards stabilisation, but there is a major obstacle. The conflict in Ukraine could take centre stage and derail the recovery. Vladimir Putin’s priorities are complicated. If Putin’s goal is to build a strong Russia, he should reduce trade barriers, deregulate domestic oligopolistic markets and strengthen the rule of law. This would boost the country’s growth rate. The problem for Putin is that such reforms would undermine the crony capitalism that is inherent in a system where power is based on being able to deliver economic advantages and privileges to important partners and interest groups. The power paradox, that you can build economic power without letting go of control, is obvious in Russia.

Putin’s popularity has been built by portraying Russia as a country under siege. In this mentality, Russia represents a different culture, a stronger, more conservative and more robust society than the declining and arrogant USA and the weak and divided Europe. According to this line of thinking, Russia’s unique culture, formed by its history, orthodox religion and location, is continuously being undermined by the western world. Russia has to be on its guard and will have to be strong when it deals with other countries. The outside world is threatening to Russia and it takes a strong leader to stand up for Russia.

When Putin has confronted Russia’s perceived enemies, whether it’s in Chechnya, Georgia, Ukraine or Syria, his popularity has increased, and in September, a parliamentary election is upcoming. There is a risk that a slow recovery in the Russian economy will motivate Putin to escalate the conflict in Ukraine once more. Recent comments from Russia about terrorism in Crimea being supported by the Ukrainian government are very worrying. It’s possible that Putin wants to take advantage of the power vacuum in the US during the Presidential election.

The resignation of Sergei Ivanov, Chief of Staff and former Minister of Defence, has been interpreted as a move by Putin to strengthen his own control even further, which could be a preparation for escalating the conflict. If this happens, sanctions will remain for a longer time period and could also potentially be reinforced.

A sustained recovery in Russia has to come on the back of a recovery in energy and commodity prices and a de-escalation process and re-engagement with Europe. Russia is a European country and can only prosper as a European Country, but this will not happen before the government in Moscow accepts this fact.

China: rebalancing, stability – and nationalism

China is slowing down, but the near-term outlook has improved somewhat and growth is likely to remain above 6% in 2016 and 2017. Credit growth is a source of concern, but the main scenario is that the authorities will manage to avoid a credit crisis. The reform process in China has been too slow to truly alter the situation of somewhat slower growth. The rebalancing towards growth based on domestic consumption and services, switching from the old model of export and manufacturing investment, is ongoing and well on track. It remains challenging to put SOEs (State Owned Enterprises) under increased market discipline, strengthen financial governance and constrain rapid credit growth, without reducing growth and undermining political stability.

The robustness of the Chinese economy is reinforced by an economic policy that focuses on stability. The fiscal deficit will be about 3% of GDP 2016, and then will gradually move down towards 2%, while the gross debt of the public sector is slightly above 40%. The current account has been in surplus for a long time and is expected to be stable at around 2.5% of GDP for the coming years.

From a political point of view, it is important to note that a growth driven by consumption and the service sector will have a bigger impact on citizens’ living standard and produce more jobs, even if it means a slightly lower overall growth rate from the previous model. This is important to the political support for the rebalancing.

The political narrative in Beijing is focused on domestic stability. Growth and employment are key factors for support for the CCCP. To keep China together and to safeguard the power of the CCCP are tasks that give the leadership a bigger assignment than they could reasonably ask for. The support for independence in Tibet and Xinjiang, underpinned by raising Islamic tendencies among the Uyghurs, is strong. Inequality, social insecurity, a rapidly ageing population and pollution are all headaches without simple solutions.

China’s economic development is more dependent on the global economic order than any other rising power in history. Some 70-80% of high-tech exports are based on Foreign Direct Investment. China is far more dependent on foreign trade than the US or Europe. Therefore, China has a strong self-interest in global stability. China has access to natural resources from Africa and Latin America, while oil imports from the Middle East are increasing. China has shown that it can safeguard its interests without using force. The 19th century race to Africa by the colonial powers will not be repeated and is unlikely to cause tension between China and the US, as it once did between Great Britain, Germany and France. Nationalistic feelings have, and will be, exploited to strengthen the popularity of the CCCP, but it is unlikely that Xi Jinping would follow in the footsteps of Vladimir Putin.

There is strong nationalistic sentiment in China, even if it has been contained so far. The historical presumption has been that nations become more moderate when they modernise and transform into middle income countries. Lately that truth has been challenged by the fact that a number of middle income countries have experienced a shift in more conservative, more religious and more nationalistic direction.

Poland (US$26,000 per capita), Russia (US$25.000) and Turkey (US$20.000) are three examples which prove that increased economic welfare doesn't necessary mean changing values. China is getting richer and more powerful. For its neighbours, a successful China is preferable. Economic stagnation in China is likely to increase social tensions and political uncertainty, but success does not come with any guaranties for modernisation and is no reliable vaccine against nationalism and populism.

The RMB appreciated some 10% during 2015, but has fallen back almost 5% in 2016. It is close to its fundamental value, according to the IMF (an interesting observation, given that Trump keeps reiterating that China is manipulating its currency). The large capital outflows have been moderated and reserve levels remain strong. If growth were slowing down further, it would be logical to push monetary policy in a more expansionary direction. Inflation dipped below 1.5% last year and picked up to 2% this year, which is very low for an emerging market country. More expansionary monetary policy would imply that the RMB would depreciate further during 2016. If this can happen in a gradual manner, then it is not a major issue, but it will put pressure on some of the other EMCs, particularly Brazil, and other countries with a strong dependency on oil and commodities.

Oil returns to the centre stage

Oil prices are likely to continue to increase, but the setback over the summer has had an impact on sentiment for emerging markets. The balance between supply and demand is pointing towards somewhat higher prices, but the dynamic between producer countries is difficult to predict.

After the collapse of the oil prices, the oil industry has hit a floor. The number of oil rigs in the USA has gone from close to 1,650 rigs to down to around 300. The rig count has, however, bottomed out during the summer months and is now increasing slowly at the Permian Basin, and some 80 rigs have been added since May (Eagleford and Williston are going sideways). The International Energy Agency, IEA, has predicted that shale oil production in the USA could be heading towards 15 million barrels per day (bpd). The US was producing some 8 million bpd in May, down from almost 10 million in early 2015 (Saudi Arabia increased production from 9.5 to close to 11 million bpd, and Russia from 10.5 to 11 million during the same time period, while Iran is getting to a production level slightly below 4 million bpd).

All the major oil companies have reduced their capital spending. The oil service sector is now in cost-cutting mode. This has also meant that the potential supply has adjusted and the ongoing depletion of existing fields is reducing production (at a rate of 5-10% per year). The cost reduction in the production, both in conventional, shale and offshore, has been much faster and bigger than expected. Inventories are now appearing to be better balanced. We have also seen temporary supply disruptions in Canada, Nigeria, Northern Iraq and Venezuela during 2016. The refinery capacity in Europe has been reduced and is flat in the US.

A more constructive tone from the new Saudi Arabian Energy Minister, Khalid Al-Falih, might be seen as an indication that OPEC and Russia are getting closer to some coordination. However, I remain sceptical about OPEC coordination. OPEC and Russia cannot control production levels in the US, where the biggest potential for increased production exists going forward. The conflict between Sunni Saudi, Kuwait and the UAE and Shia Iran is undermining the logic of OPEC. If you are willing to engage in pseudo-military conflicts in Syria, Iraq and Yemen, it seems difficult to conduct price coordination. The fiscal problems in Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Nigeria and Russia also mean that production restrictions are difficult to implement.

Historically, OPEC coordination has meant that Saudi Arabia is restricting production while most other producers are continuing without reductions, which is unacceptable for Saudis today. The fact that Saudi Arabia has launched a program of broad-based structural reforms also has an impact. The Saudi economy is completely dominated by the oil industry, and oil subsidises government projects (the private sector accounts for less than 15% of GDP). The leading policy maker, Mohammad bin Salman, Deputy Crown Prince, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defence, has set the goal of becoming independent of oil. This will be very difficult to achieve under any circumstances and, without oil revenues, it is difficult to see how it will happen.

The overall budget deficit reached above 16% of GDP 2015 and the gross debt has gone from 1% of GDP 2014 to 30% of GDP in 2018. The current trajectory is unsustainable and there has to be a substantial fiscal restructuring program going forward of a magnitude equal to what has been seen in Greece and Ireland.

To perform broad-based structural reforms and cut back the government deficit at the same time is difficult. To do it in a country that has been dependent on government subsidies for decades and where the private sector is very weak is even more complicated. In addition, the government does not have the legitimacy of a democratic mandate and the young generation is becoming more and more supportive of Sunni Wahhabi radicals; two thirds of the population is below the age of 25. The reform process in Saudi Arabia is going to be difficult enough; implementing it without getting the highest possible oil revenues appears potentially dangerous.

A recovery of the oil prices has to happen on the back of a recovery in Asia. China has been the main driver of energy demand over the last decade. A more stable level of growth in China is an important factor. If India, Indonesia and the rest of Asia can accelerate growth going forward, this will also be important. In a global recovery, oil prices should continue to increase, maybe reaching US$55 per barrel during 2016 and above US$60 during 2017, and this would reduce the risk level in the global economy.

The conclusion is clear. The global economy and the financial markets will be captured by political risks and geo-political uncertainty. The macroeconomic situation might have improved, but the political situation has deteriorated. The summer vacation is over. The autumn is almost here, winter is coming. As the old Viking proverb goes, it could be a winter of the wolves.

Have you read

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on European UnionSee all

Kimberley Botwright and Spencer Feingold

March 27, 2024

Simon Torkington

February 8, 2024

Mirek Dušek and Andrew Caruana Galizia

January 17, 2024