How 3D printing will disrupt manufacturing

Hard to believe that digitalisation might affect manufacturing to the same extent it has affected and changed media. Record shops did not survive the digital reproduction of music: the last Virgin Megastore in the US closed five years ago, following the earlier demise of many thousands of smaller retailers. Newspapers had to rethink their content and delivery systems—the New York Times recently started to deliver summarised news directly to smartphones. What if 3D printing, also called “additive manufacturing”, goes mainstream and allows each one of us to reproduce tangible goods remotely?

Conventional models of production rely on large, interlinked manufacturing facilities and the vast complex of supply and delivery relations that revolve around them.

Digitalisation has potential to disrupt this system. It is already disrupting business-as-usual in certain niche industries, prosthetics and medical implants among them, because 3D printing makes customisation easier and design processes faster. MIT’s Dr Hugh Herr prints plastic prosthetic sockets that once were made almost artisanally. Now, the part comes out already perfectly adjusted to individual requirements. If not, it can be remodelled and reprinted in no time. “Rigorous quantitative processes of developing unique elements of a prosthesis reduce discomfort of the patients and drive down the price,” he explains.

For standardised items, the cost advantage of additive manufacturing may be less significant since the technology does not yet allow high-volume production, while mass manufacturing decreases the average cost. It can still be of use, however. For example, 3D printing can help reduce tooling costs by up to 30% because the piece can be printed in its final form rather than carved from a larger piece of material—saving time and reducing waste. Marco Annunziata, GE’s chief economist, agrees: “We project that by 2020 over 100,000 parts will be additively manufactured by GE Aviation, which could reduce the weight of a single aircraft by 1,000 pounds, resulting in reduced fuel consumption.”

One of the future scenarios in an Industrial Research Institute study imagined a collapse of mass manufacturing under the strain of 3D printing. A recent McKinsey report predicts that more companies will adopt the technology by 2025 and change the way they add value to products, altering their focus to personalisation. 3D printing could also reduce the entry costs into markets, allowing niche businesses to spring up closer to points of consumption. Over time, the source of competitive advantage will shift towards such areas of the value chain as design or even the ownership of customer networks. In such a situation, world economies reliant on scale manufacturing at low cost, like China, would appear to be the losers.

Chris Caplice, MIT’s executive director of the Center for Transportation and Logistics, believes that 3D printing fits into the general trend of decentralisation of manufacturing and scale reduction, joining robotics, automation and other technologies. But the real impacts, he told Look Ahead, can be discerned only in a long-term perspective.

Parcel delivery companies will be under the most pressure. However, they are also not waiting to be cannibalised. Same as the engineering giants (Airbus, Boeing, GE, Ford, Siemens), they have already started to hybridise additive and conventional manufacturing. UPS, FedEx and other firms have launched pilot projects to explore the technology and leverage their decentralised facilities. “They can become, for example, local hubs for 3D printing of small parts,“ Dr Caplice says.

Logistically, the technology could also change the distribution and the nature of goods: more raw materials for 3D printers than end products would be pushed towards decentralised areas. Because of fewer long hauls, lower volume would also be coming in through ports.

The changes, Dr Caplice concludes, will take decades. “We will have driverless cars way before we have that level of sophistication.”

This article is published in collaboration with GE Look Ahead. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with Forum:Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Julia Taranova writes for GE Look Ahead

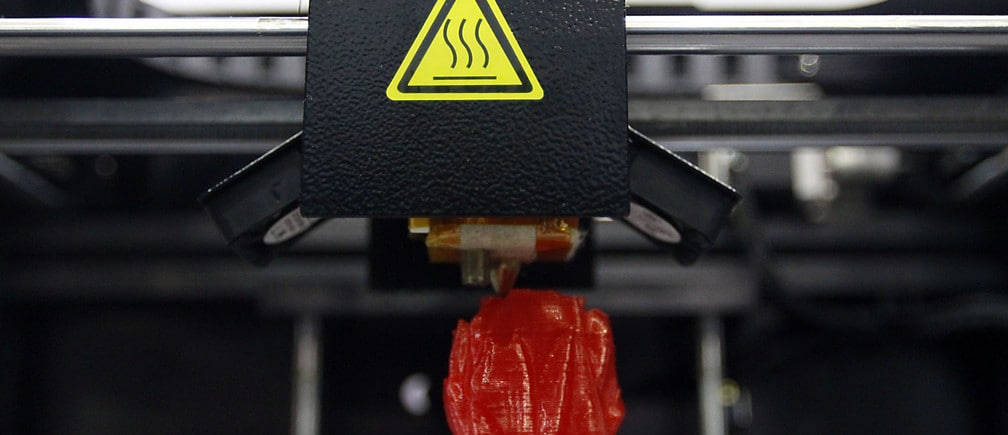

Image: A figurine is printed by Aurora’s 3D printer. REUTERS/Pichi Chuang

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Emerging Technologies

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Emerging TechnologiesSee all

Dr Gideon Lapidoth and Madeleine North

November 17, 2025