What happens when labour markets are deregulated?

Stay up to date:

Competitiveness Framework

Global imbalances and labour market deregulation trends

The late 20th century age of globalisation witnessed growing current account imbalances, financial market development within and across countries, and deregulation of national labour markets following the OECD (1994) guidelines. In Bertola and Lo Prete (2015) we analyse the implications of labour market reforms for international imbalances. In theory, labour market deregulation has two effects on an open economy’s current account balances. To the extent that it fosters future growth, it decreases current savings by consumption-smoothing households that anticipate an increase in their future income, and tends to make the current account more negative. But by making labour income flows more uncertain, labour market deregulation also induces stronger precautionary savings, and may have the opposite effect on external balances. As we discuss in the paper, the first effect should predominate when financial markets make it possible to prevent labour income risk from influencing consumption patterns. In reality, however, financial markets are far from being perfect and complete. Empirically, we find that labour market deregulation was on average positively related to current account surpluses between the 1980s and up to the mid-2000s in a panel of OECD country-level data, and that the relationship between reforms and external balances was shaped by households’ access to credit. Indeed, reforms were negatively associated with current account imbalances in the less regulated and more market-friendly Anglo-Saxon countries and, within Europe, in countries where financial markets were or became more developed.

Causes and effects of labour market deregulation

At the turn of the millennium, labour market rigidities were thought to be harmful in the face of international competition, and financial market development was seen to be the appropriate way to reconcile economic and social objectives. The 2008–2009 financial turmoil casted doubts on the benefits of financial market development and excited calls for some re-regulation of labour and credit markets, making it all the more important to derive insights about the redistribution role of national policies and their impact at the country level. Our analysis of pre-Crisis data indicates that structural labour market reforms that improve productivity growth tend to bring current accounts towards surplus positions in initially highly regulated countries, and that the strength of this effect depends on country-specific indicators of borrowing constrains. Within each country, labour market deregulation exposes consumption to more risk – when reforms have a negative effect on country-level consumption, their welfare effect is negative on average, and particularly negative for low-wealth individuals.

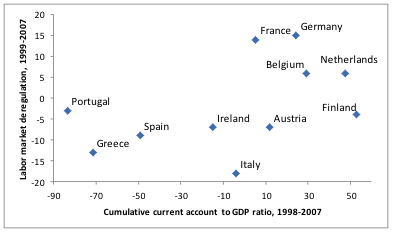

A related pattern is observed in the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). Figure 1 shows that flexibility-oriented reforms (represented in cumulative terms on the vertical axis) were associated with more positive current account positions in the period between adoption of the single currency and the Crisis. The EMU experience illustrates not only the implications, but also the sources of variation of labour market rigidity. The evidence is consistent with a causal relationship running from reforms to trade balances, where countries gain or lose competitiveness by increasing or reducing labour market flexibility. At a deeper level, however, the uneven cross-country pattern of labour reforms can be explained by simple politico-economic mechanisms as in Bertola (2014). Capital mobility across the boundaries of countries with independent labour policies changes the pros and cons of labour market regulation in ways that, like international financial flows, depend on countries’ relative capital intensities. If the politically decisive individual in (say) Germany is capital-poor relative to the German average, but less capital-poor relative to the newly integrated financial market, the politico-economic equilibrium in Germany should swing towards deregulation more strongly than in (say) Spain, where the politically decisive individual becomes even more capital-poor and the labour market reform implications of economic integration are smaller and ambiguous in sign. The pattern of labour market reforms that in Figure 1 was associated with EMU capital flows left indebted countries in a position of relative labour market rigidity at the time of the crisis, and made it necessary for them to accept more labour market flexibility.

Figure 1. Pre-Crisis labour market reforms and cumulative current accounts

Notes: Reform trends are proxied by the cumulative count of measures deemed to be increasing flexibility, net of those deemed to decrease it, in the European Commission Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs and Economic Policy Committee LABREF database (Turrini et al.2014). Current account and GDP data are from Eurostat.

Rethinking regulation

These arguments provide interesting insights for post-Crisis developments, especially in Europe. In a world where labour market deregulation is associated with more positive current account positions, reforms may contribute to reduce current account imbalances if deficit countries make their labour markets more flexible, and surplus countries reintroduce some labour market rigidities. Rebalancing trade patterns through competitiveness takes time and requires credibility – despite post-crisis reforms, current account deficits in the EMU have been reduced mostly by internal demand compression. Policy measures that increase labour market regulation in surplus countries, such as the introduction of a minimum wage in Germany, may contribute to reducing international financial imbalances. Theory and evidence suggest that this might occur also and perhaps especially by reducing labour income uncertainty, and encouraging consumption by working households, in countries where economic integration triggered capital outflows that, while supporting capital incomes, made workers suffer lower wages and more unstable employment.

This article is published in collaboration with VoxEU. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Giuseppe Bertola is a Professor of Economics, EDHEC Business School; CEPR Research Fellow. Anna Lo Prete is a Research Fellow, Department of Economics “Cognetti de Martiis”, Università di Torino.

Image: Workers on the assembly line replace the back covers of 32-inch television sets at Element Electronics in Winnsboro, South Carolina. REUTERS/Chris Keane

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Alejo Czerwonko

May 20, 2025

Matthew Wilson and Ratnakar Adhikari

May 20, 2025

Aengus Collins

May 14, 2025

Rya G. Kuewor

May 13, 2025

Tea Trumbic and Dhivya O’Connor

May 13, 2025

Navi Radjou

May 8, 2025