Should new EU countries join the banking union before the Euro?

John Bluedorn

Senior Economist in the European department, IMF

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

European Union

All European Union members, except Denmark and the United Kingdom, are expected under EU treaties to eventually adopt the euro. Six Central and Eastern EU members – Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania – are yet to do so.

In the meantime, these countries have a decision to make: Should they opt in to the Banking Union before adopting the euro? Such a move may offer greater insurance against shocks, but at a certain cost to policy flexibility. In a recent study, we explore some of the trade-offs that countries need to weigh.

Banking Union origins

Rationale: The recent crisis led to the realization that a common currency area needed centralized bank supervision and resolution to overcome financial fragmentation and break the link between bank and sovereign stress.

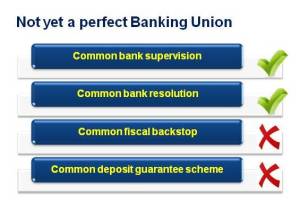

Elements: The two main arms of the Banking Union are the Single Supervisory Mechanism and the Single Resolution Mechanism. The first aims to raise the credibility and quality of bank supervision by removing the distinction between home and host supervisors. The second aims to sever the links between bank and sovereign stress by unifying the bank resolution and restructuring frameworks across countries and providing a common, industry-funded backstop. The other two elements – a common fiscal backstop and common deposit insurance – are also essential to complete the Banking Union.

Benefits: Once the Banking Union is complete, it is expected to raise the quality of supervision, lower bank compliance costs, remove existing barriers to cross-border banking activity, lower resolution costs, and ultimately, lower bank funding costs.

Missing pieces

Not all key elements of the Banking Union are yet in place. With the SSM and SRM now operational, an effective common fiscal backstop is still needed to break the sovereign-bank links. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is currently acting asde facto common fiscal backstop for euro area banks, but its powers are limited and the threshold for access is high. The industry-financed Single Resolution Fund (SRF) will be fully funded and mutualized only by 2024. Finally, there is still no pan-European deposit guarantee scheme.

Different rules

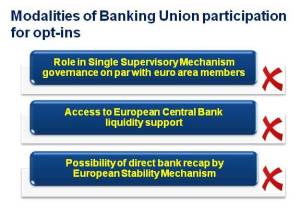

Non-euro area members of the Banking Union would not be treated in the same way as the euro area members. Non-euro area countries are not members of the European Central Bank’s (ECB) Governing Council, which is charged with adopting decisions drafted by the SSM. Further, non-euro area opt-ins will not be eligible for direct bank recapitalization by the ESM and would not have direct access to the ECB liquidity facilities.

Trade-offs

The calculus of the Banking Union opt-in decision for non-euro area members is complex and there are many moving parts. One way to look at it is whether the support they would get from the Banking Union makes it worthwhile to shift decision powers from the national level:

- LESS national policy flexibility vs. COMMON insurance. At present, local supervisors have significant flexibility to impose macro- and micro-prudential requirements and use early intervention powers to mitigate shocks affecting financial stability and credit provision. Upon joining the Banking Union, some of this flexibility could be lost. This loss could be mitigated by having access to common insurance – fiscal, industry-funded, and deposit insurance backstops. However, some of these are not yet in place or not available to non-euro area BU members.

- LESS national control over cross-border flows vs. COMMON liquidity backstop. Banking Union membership would limit the local authorities’ ability to ring-fence the euro area banks’ subsidiaries. This is important for the new EU member states, whose banking systems are dominated by the euro-area owned banks which are systemically important in the host countries but account for a small part of the parent bank balance sheets (see Figure). Having less control over cross border flows in times of stress could be compensated by having access to common liquidity backstop. The latter, however, is not available to the Banking Union opt-ins.

- LESS national control over bank resolution vs. COMMON resolution fund.Upon joining the Banking Union, decisions on whether or not to resolve a bank would be taken at the Banking Union level. Having less control over resolution decisions could be compensated by having access to a common backstop. However, until the SRF is fully mutualized, financing of the resolution process will remain largely a responsibility of individual countries.

Decisive factors

The cost-benefit analysis could lead to different conclusions for different countries, depending on their fundamentals. It may be the case for some countries that an immediate boost to the quality and credibility of bank supervision and eventually having access to larger backstops would outweigh all other considerations. For others, the attractiveness of early opt-in will likely hinge on the Banking Union’s ability to establish a fully equivalent treatment of euro area and non-euro area members, as well as its credibility and operational excellence.

This article is published in collaboration with IMFDirect. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: John Bluedorn is a Senior Economist in the European department, where he is part of the euro area team. Anna Ilyina is currently an Advisor in the European Department (EUR) at the International Monetary Fund, where she heads the Emerging Economies Regional Studies Division. Plamen Iossifov is a Senior Economist in the IMF’s European Department.

Image: The headquarters of the European Central Bank (ECB) are pictured in Frankfurt. REUTERS/Ralph Orlowski

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Geographies in DepthSee all

David Elliott

July 19, 2024

Tariq Malik and Prerna Saxena

July 12, 2024

Ange Chitate

July 10, 2024

Ratnesh Bedi, Asheesh Sastry and Toong-Yuen Chong

July 3, 2024

Why Asia’s time is now: what's fueling Asian growth and what does it mean for the rest of the world?

Neeraj Aggarwal and Aparna Bharadwaj

June 24, 2024