Will some countries be 100% renewable by 2030?

Stay up to date:

Sustainable Development

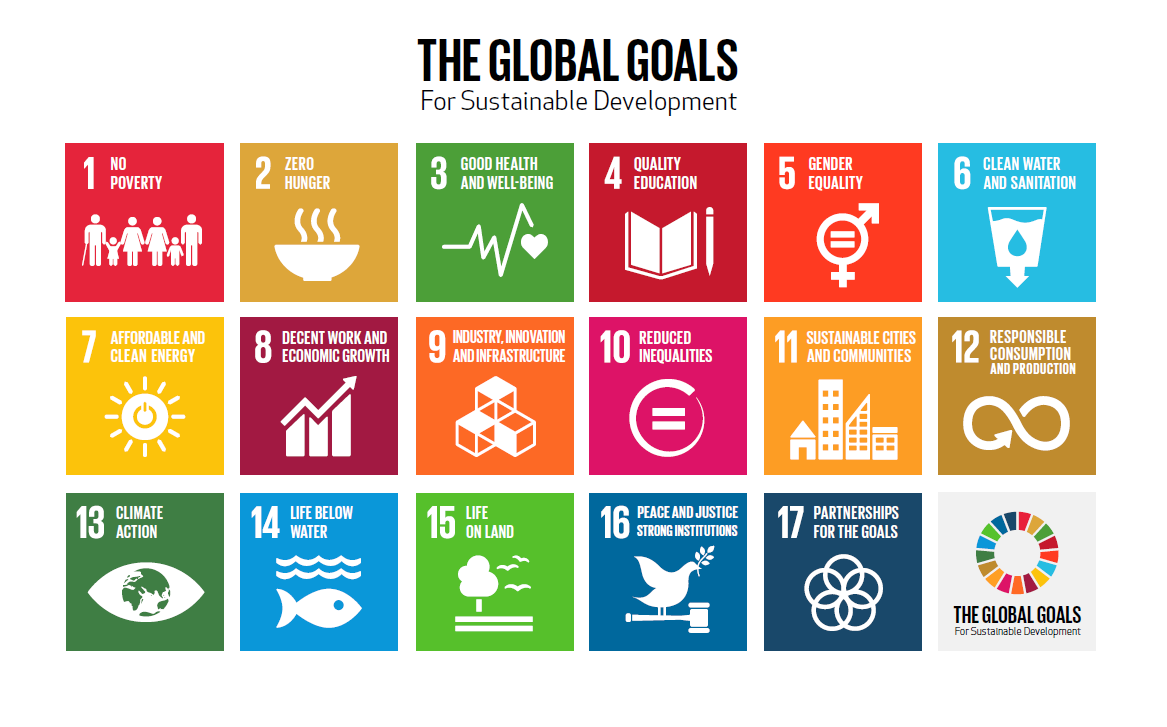

This is part of a series on the Global Goals for Sustainable Development, in collaboration with the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Size now matters: in a single human lifetime we have become a big world on a small planet.

This simple fact is as profound as Copernicus’s conclusion that the Earth revolves around the sun or Darwin’s evolution by natural selection. A crucial difference though, is that the need to act on this information – as global citizens and as world leaders – has become critical.

Moreover, this fact means our economic schools of thought, from Marxism to neoliberalism and everything in between, are obsolete. Given this knowledge, perhaps future economists will view their followers as no wiser than the medieval academics who counted angels on pinheads. We have built our global economic logic on the assumption that our planet is endless and can deliver natural capital for free and take abuse – such as abrupt climate change and mass-extinction of species – without sending any invoices back to the economy. A reasonable assumption until two decades ago. Not any longer. Now we have ample scientific evidence that we are hitting the ceiling of our planet’s capacity to support world development, without triggering extreme shocks, such as droughts, floods and heatwaves.

Source: Jakob Trollbäck

Source: Jakob Trollbäck

The evidence is so overwhelming, the political narrative is shifting. World leaders meet in New York this weekend at the United Nations summit to agree Global Goals for sustainable development, including to eradicate poverty and plan for long-term prosperity within planetary boundaries. The goals apply universally to all nations. This final awakening comes as the invoices start rolling in: the Californian drought and the Indian heat waves, to take two examples.

Better late than never.

The UN resolution could not be clearer: “The survival of many societies, and of the biological support systems of the planet, is at risk.”

The goals replace the Millennium Development Goals, launched in 2000, with the laudable target of ending extreme poverty. Extreme poverty has halved In the same year, and with less fanfare, the Nobel laureate Paul Crutzen proposed there was now ample evidence to say Earth has switched to a new state – a new geological epoch dominated by humanity, the Anthropocene.

This conclusion is beyond arcane geological nomenclature. The stable climate and biosphere over the last 12,000 years has provided the foundation for the human civilization as we know it. But this stability can no longer be taken for granted. Earth is now slipping beyond Holocene boundaries. We are participating in an uncontrolled experiment. As physicist Richard Feynman once remarked, we are tickling the tail of a dragon. We are in the midst of a sixth mass extinction of species on Earth, we are observing grand changes in the chemistry of the oceans and the atmosphere and we are receiving early signs that parts of the polar regions may be destabilizing.

When British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan was asked what was the most difficult thing about his job, he famously responded, “Events, dear boy. Events.” We can trace the crisis in Syria to a complex combination of environmental and socio-economic drivers. Food price hikes caused by crop failures in Russia and Australia contributed to sparking the Arab Spring in Egypt and Tunisia mobilizing activists in Syria. A four-year drought in the country, linked to climate change, drove farmers to cities, leading to political instability, interacting with the social uprising to ignite a bloody civil war leading to a disastrous refugee crisis.

While politicians lurch from crisis to crisis, researchers studying resilience and complex systems are attempting to understand the Anthropocene and the rapid global feedbacks between our economic and political world and Earth’s biosphere.

Alarm is growing. Recently my colleagues and I published research identifying nine planetary boundaries we must remain within or risk crossing potentially irreversible tipping points and exiting the Holocene with a sharp shock. We estimate we have already crossed four boundaries relating to climate, biodiversity, deforestation and fertilizer use, placing us in a danger zone. Parts of the biosphere – the oceans, ice sheets, waterways and land – are reaching breaking point.

But, while size matters, population is not the problem, as is so often assumed. We have already reached peak child; population is on track to stabilize. With careful management of our natural resource base and reduction of waste, there will be enough food for all.

The culprit is resource use on a planetary scale. The world needs a new school of economic thought that acknowledges the reality of the Anthropocene.

Take fish. Global trade provides fish in the store at the same price year round. Fish stock collapses in a region pushes fishermen further afield but fish prices stay constant. Consumers only receive the price signal when vast marine ecosystems are on the verge of collapse. But when stocks collapse, like the cod stocks did off Newfoundland in the 1990s, that’s it. They don’t easily recover. Transnational fishing corporations should have credit ratings that reflect their sustainability.

Or, the fool’s errand that is the race for oil in the Arctic. The world must become fossil free. This is not a value judgment. This is for the stability of the Earth’s living system. We are drilling holes in our lifeboat. The only question seems to be, how many?

But the great irony is it is possible to have prosperity and wellbeing and end poverty without global environmental degradation. Many analysts indicate we are on the verge of a new revolution, from digital highways to nanotechnology, biotechnology, clean energy systems and sustainable farming systems. Uncontrolled, however, this new era of grand innovations is at risk of propelling the world even faster towards the Holocene precipice. The Global Goals provide the necessary compass point. And we have the economic tools to succeed. A transition to a circular economy that values natural capital and uses policy instruments to place planetary boundaries on “no go” terrain, such as developing within a 2°C global carbon budget, are real, operational, frameworks that can generate growth within the planet’s limits.

A recent analysis concluded that the goals were not a utopian ideal. Rather, some countries, notably the Nordics, were well on their way to achieving them. Indeed, emissions in over 40 countries have been falling for over a decade and the Danish capital Copenhagen has committed to be carbon free by 2025.

This leads to an intriguing possibility. I predict within a year the first countries will announce they will be fossil-fuel free by 2030-2040. This will send an unmistakable signal to the world’s economy and mark the start of a new economic school for the Anthropocene.

Have you read?

How can we eradicate poverty by 2030?

10 facts about the Sustainable Development Goals

Author: Johan Rockström, Director, Stockholm Resilience Centre

Guest editor of this series is Owen Gaffney, Director, International Media and Strategy, Stockholm Resilience Centre and Future Earth

Image: A general view shows solar panels to produce renewable energy at the photovoltaic park in Les Mees, in the department of Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, southern France March 31, 2015. REUTERS/Jean-Paul Pelissier

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Sustainable DevelopmentSee all

Katerina Hoskova

August 26, 2025

Thomas Brostrøm and Sandeep Kashyap

August 26, 2025

Ridwan Sorunke and Alyse Schrecongost

August 25, 2025

Thom Townsend

August 20, 2025

Charles Bourgault and Sarah Moin

August 19, 2025

Yufang Jia and William Jernigan

August 18, 2025