Why talent is key to unlocking Africa’s competitiveness

Stay up to date:

Competitiveness Framework

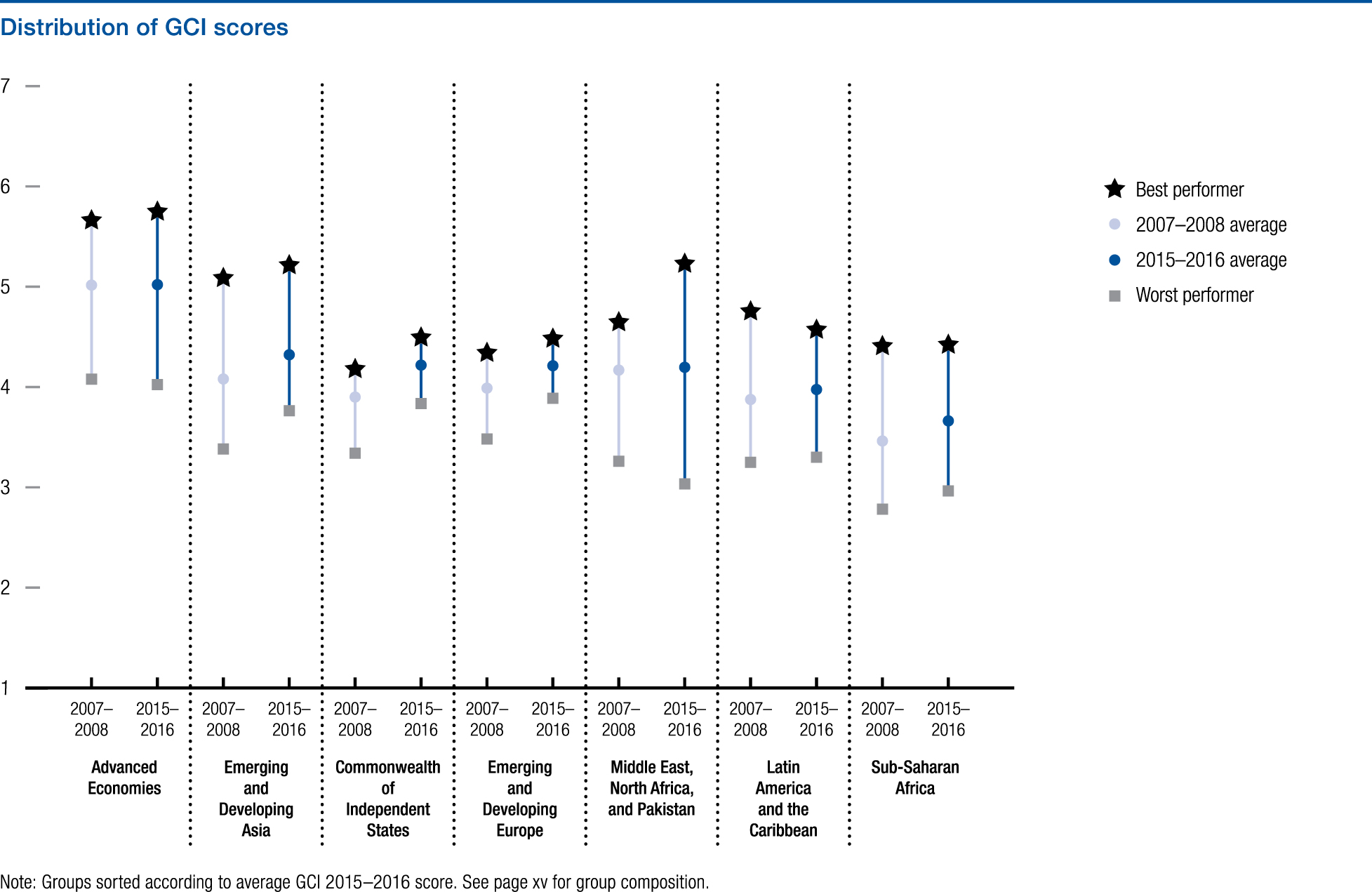

Sub-Saharan Africa continues its solid performance, set to grow at 4.4% in 2014, second to emerging and developing Asia, bearing witness to the region’s economic potential. However, Africa’s levels of productivity and competitiveness remain low, largely held down by the more basic drivers of competitiveness, such as weak institutions, poor infrastructure and insufficient health and education sectors.

In addition, wide regional disparities persist. While the region’s most competitive economies – Mauritius (46), South Africa (49) and Rwanda (58) – feature in the top half of this year’s Global Competitiveness Index, an assessment of 140 economies, 15 of the bottom 20 economies are sub-Saharan with Guinea closing the list at 140.

Low levels of competitiveness are a point of concern both in the short and long term. In the long term, they cast doubt on the region’s ability to embark on a sustainable path of development towards increased prosperity. In the short term, they limit its ability to weather important downside risks, such as the recent fall in resource prices and increased investor scrutiny of emerging market risks. In this aspect, a trend analysis in this year’s Global Competitiveness Report shows evidence that more competitive economies are also those that are more resilient, providing a strong rationale for sub-Saharan stakeholders to jointly advance in efforts to enhance the region’s competitiveness.

This year’s Global Competitiveness Report identifies talent at the heart of a competitive and, therefore, resilient economy. Countries that educate, train and reward people appropriately, and ensure that workers have the skills to attain productive employment, are also those that are most competitive. This holds true both for advanced and developing economies and is an important message for sub-Saharan Africa in view of its growing labour force that is projected to exceed that of the rest of the world by 2035.

Increasing levels and quality of education in sub-Saharan Africa are an important determinant for advancements across all sectors of the economy: in the agriculture sector through enhancing skills in biotechnology as one way to increase the sector’s low productivity; in the manufacturing sector to help increase the attractiveness of African producers and enable technology and knowledge transfers for the region’s participation in global value chains; and in the services sector, where especially tertiary enrolment has been shown to be important in developing countries, primarily via skills and entrepreneurial activity. Indeed, a highly educated workforce is needed to develop high-value-added service exports such as finance, communications and business services. Yet, despite the importance of higher education, even the levels of health and basic education of the workforce remain low in the region despite notable improvements in primary enrolment, and only a handful of small-open economies deliver somewhat on both fronts.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s need to leverage its unprecedented pool of potential talent is further complicated by the twin challenge of nurturing talent and also ensuring employment creation in the first place. While the Global Competitiveness Report discusses labour market rigidities, higher education and female participation as the primary bottleneck in advanced economies, the challenges are somewhat flipped in sub-Saharan Africa where the framework conditions of a relative flexible labour market and record levels of female participation now need to be met with adequate employment creation. Efforts across sub-Saharan African economies to improve market efficiencies generally and competition in domestic markets bear evidence to the region’s reform capacity, as is the case, for example, in this year’s rise of Côte d’Ivoire (91) and Ethiopia (109).

However, the ease of entry and exit from low-wage, low-productivity jobs and an improving business environment alone will not lead to improved competitiveness. These need to be critically complemented by competitiveness-enhancing reforms in basic requirement, such as improving institutions and bridging the infrastructure and human capital gap. This can only be done through cooperation among all African stakeholders, such as governments, business and civil society. In view of the considerable time lag for reforms in these areas to materialize, the time is now for African leaders to leverage the continent’s dormant talent and make it the centre of the region’s future competitiveness.

The Global Competitiveness Report 2015-2016 is available here.

Have you read?

The world’s top 10 most competitive economies

The top 10 most competitive economies in Europe

Author: Caroline Galvan, Economist, Global Competitiveness and Risks, World Economic Forum

Image: Students laugh and share a joke outside their classroom at the Sudan University of Science and Technology in Khartoum, Sudan, May 14, 2015.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Jill Klindt and Mandi McReynolds

May 30, 2025

Sergio Navajas and Jimena Sotelo

May 29, 2025

John Letzing

May 29, 2025

Naala Oleynikova

May 28, 2025