How the human cloud is transforming the way we work

Nestled in his “man cave”, a room crammed with cardboard boxes and fishing lures in his Rhode Island home, Set Sar is earning money by letting a company track the tiniest movements of his eyeballs through his computer’s webcam.

About 10,000 miles away, Adi Nagara is hiding from the heat in his air-conditioned bedroom in Jakarta, researching an Indonesian industry for a consultancy firm. Though they are doing different tasks for wildly different sums on different sides of the world, the two men are connected. They are both members of the “human cloud”.

Employers are starting to see the human cloud as a new way to get work done. White-collar jobs are chopped into hundreds of discrete projects or tasks, then scattered into a virtual “cloud” of willing workers who could be anywhere in the world, so long as they have an internet connection.

Some of these tasks are as simple as looking up phone numbers on the web, typing data into a spreadsheet or watching a video while a webcam tracks your eye movements. Others are as complex as writing a piece of code or completing a short-term consultancy project.

The uniting factor is that these are not jobs but tasks or projects, performed remotely and on-demand by people who are not employees but independent workers. Much of it is, in effect, white-collar piecework. Employers spent between $2.8bn and $3.7bn globally last year on payments to workers and the online platforms that act as intermediaries in the human cloud, according to a recent Staffing Industry Analysts report.

To its champions — the people who run platforms and others who believe we are on the threshold of a flexible work revolution — the human cloud promises to eliminate skill shortages, ease unemployment black spots and create a global meritocracy where workers are rewarded solely for their output, regardless of their location, education, gender or race. Some even say it could return us to the age of the cottage industry, before we crammed into factories or offices and lost control over our work.

“What we see today is people taking ownership again of the means of production, because you just need a computer, your brain and a wifi connection to work,” says Denis Pennel, managing director of Ciett, the international lobbying organisation for private employment agencies. “So actually, Marx should be very happy!”

Critics turn to history for their analogies too, but they talk of dead-eyed operatives on production lines, not happy artisans. In the human cloud they see a wild west of unregulated virtual sweatshops, breaking down service sector work into its constituent parts, making people compete in a worldwide race to the bottom. “It makes Adam Smith’s famous division of labour in pin-making look modest,” says Guy Standing, an academic and author of several books about the “precariat” and the growth of insecure work.

Turkers and nerds

Whether the human cloud is more utopia or dystopia depends, at least in part, on where exactly in its hierarchy you find yourself.

Mr Sar is near the bottom, as he readily admits. “We’re just getting crumbs as far as what we’re getting paid for it,” says the 29-year-old from Providence, capital of America’s smallest state.

He joined the human cloud through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, a site run by the online retailer where “requesters” pay “Turkers” to do simple microtasks that humans are still marginally better at than computers, such as transcribing audio clips, filling in surveys or tagging photos with relevant keywords. The name Mechanical Turk refers to a fake chess-playing machine from the 18th century that fooled onlookers into believing it was an automaton when in fact there was a person hiding inside. Amazon — whose tagline for the platform is “artificial artificial intelligence” — calls the jobs on offer “human intelligence tasks”, or HITs. Many of them only pay a few cents apiece.

Not all the work on offer is so futuristic. Take the cloud call centres that assemble armies of “independent agents” who work from home, pay for their own phone and internet, and only get paid when they are actually on a call. The average “talk-time rate” at one large cloud call-centre is $0.25 per minute, though some clients also offer sales commission.

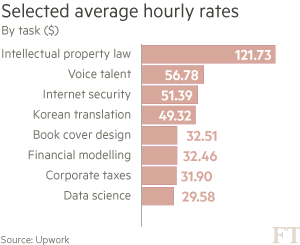

Further up the hierarchy are platforms like Upwork, Freelancer and People per Hour, which feature more skilled tasks such as copywriting, IT and design work. Upwork, formed last year by a merger of two large platforms, is now the behemoth of the human cloud, processing about $1bn worth of payments from employers to workers last year (of which it takes a 10 per cent cut). The company took 10 years to reach $1bn, but reckons it will reach $10bn in another six. “It’s a thing that takes a long time at the beginning,” says Stephane Kasriel, its chief executive. “Then at some point it hits a tipping point, it becomes mainstream.”

Some of these sites invite workers to “bid” for the tasks on offer — specifying how quickly and for what fixed price they could do the work. Others offer payment by the hour. In most cases, employers and workers give each other star ratings after they finish a task, much like on eBay or Airbnb, allowing them to build a track record. Reputations are important: human cloud platforms know they need to link employers with good workers to encourage return visits, so many are starting to use “big data” algorithms to recommend certain workers for certain gigs.

People per Hour has set up a sister site, SuperTasker, which uses a smaller group of pre-screened workers to do fixed tasks in a fixed period of time for a fixed price: a 400-word blog post delivered in three hours costs $45, for example. Xenios Thrasyvoulou, the company’s founder, calls this “SKUs for work”. SKUs are stock keeping units — retailer shorthand for indistinguishable products.

Yet at the top of the human cloud’s hierarchy, “standardisation” is a dirty word. “It’s not a commodity — clients don’t choose on price,” says Daniel Callaghan, chief executive of UK-based MBA & Company. His platform, like US rival HourlyNerd, links companies with “consultants on demand”. Other specialist sites include Topcoder for computer programmers and Upcounsel for lawyers.

Consultants on MBA’s platform charge between £250 and £4,800 a day (then MBA adds its fee of 20 per cent). Mr Nagara, who is 30, is one of the platform’s consultants; he used to work for Australian investment bank Macquarie but moved back to Indonesia for family reasons. He reckons he earns more from his daily rate than he would as a full-time employee — though he sacrifices the security and benefits, a trade-off his parents do not understand. “They stayed with one company for decades, so when they see me being unemployed every two months they think ‘Jesus!’ They probably think I’m a disaster!”

Opportunities and costs

While many workers on these specialist sites are young and fleeing the corporate grind or topping up incomes, others are capitalising on a lifetime’s worth of knowledge. Nasa, the US space agency, once posted a challenge to find an algorithm that could predict solar flares: the winner (who Nasa paid $20,000) was a retired radio frequency engineer.

It is not hard to see the promise of the human cloud for employers, who frequently complain about skills shortages and a lack of skilled migrant workers.

Mr Callaghan says the human cloud will make such problems disappear. “You can now get whoever you want, whenever you want, exactly how you want it,” he says. “And because they’re not employees you don’t have to deal with employment hassles and regulations.”

That is particularly useful for fast-growing start-ups. Dom Bracher, a 22-year-old founder of UK-based mobile marketing company Tapdaq, uses developers and designers in Scandinavia and central Europe. “There’s no need for someone to be in the same city as you,” he says.

Susan Lund, a partner at the McKinsey Global Institute, says the human cloud can improve social mobility, too, since it allows people to amass hard evidence of their abilities regardless of the formal qualifications on their CVs.

“For somebody who doesn’t have a degree from a top university or even a degree at all, accumulating those ratings is very important — to be able to say I’ve done X hours of coding and my average rating was Y — that’s very powerful,” she says.

The other consequence of work moving online is that more people should be able to do it: the housebound or people in locations where job opportunities are scarce.

The flipside is that workers in places where the cost of living is lower can undercut their peers in more expensive countries. “You can have someone in Gothenburg competing against someone in Dakar,” Prof Standing says.

Plenty of IT and call-centre work has been outsourced to countries like India but Prof Standing believes the next wave of “silent offshoring” will be more devastating for wages and conditions in the developed world.

It is hard to test this hypothesis, since most human cloud platforms are not listed and only disclose their data selectively. Still, a lot of work appears to gravitate to low-cost countries with skilled workforces: Upwork’s biggest markets after the US by worker earnings are India, the Philippines, Ukraine and Pakistan.

But Mr Sar and Mr Nagara are evidence that the picture is complex: low-paid work does not always drift east and high-paid work does not always drift west.

Contractors or staff?

Perhaps the thorniest problem of all for the human cloud is one that has also plagued Uber, the taxi app: when should an independent worker actually be classed as an employee?

Human cloud platforms usually classify workers as self-employed, which frees them from the requirement to pay minimum wages, employer taxes and benefits like sick pay.

But lawyers and workers are challenging them: last year a cloud platform called Crowdflower offered more than $500,000 to settle a US class action lawsuit from workers who said they were really “employees” and were therefore owed the minimum wage.

Most countries’ legal systems are struggling to keep up with these new forms of work. “In these arrangements, there’s really more than one employer — the law can’t grapple with this,” says Jeremias Prassl, a law professor at Oxford university.

Jonas Prising, chief executive of ManpowerGroup, an employment agency, predicts policymakers will impose more regulations on the new platforms soon.

“Who is taking care of these individuals? Who is providing the security in terms of taxation and social security? Who is doing the work is not known, who is paying the tax is not known, the age of the people doing the work is not known,” he says.

For all that, it can be a false comparison to contrast “insecure” human cloud work with “secure” traditional jobs — particularly at the bottom of the economic ladder.

Mr Sar has a job in a warehouse, but like many low-paid employees in developed countries, his rights and protections have been hollowed out. He is employed arm’s-length by an agency, which means he can be fired on the spot and is ineligible for many benefits. In the warehouse he wears an earpiece called “The Jennifer unit”, a robot in his ear that tells him what to do and tracks his performance and his downtime.

The human cloud might not pay much, it might be monotonous, but it gives him a sense of control. “Growing up through the years I’ve always worked for someone else. You’re treated as a number and not a human,” he says.

But his work in the cloud is different. “I can stop whenever I want. I can take a break, or eat something,” he says. “The idea of being my own boss is what really attracted me.”

This article is published in collaboration with Financial Times. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: The Financial Times covers, comments and analyses the latest UK and international business, finance, economic and political news.

Image: The hands of a woman are pictured as she blogs from her living room. REUTERS/Vivek Prakash.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Future of Work

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Jobs and the Future of WorkSee all

Kate Bravery and Mona Mourshed

December 20, 2024