Work stress: why women have it worse than men

At more speeches to women than I can count, the question I pose is: “How many of you see yourself as CEO of your company?” Maybe one or two women raise their hands. Usually it takes going down the hierarchy to department or division level before a critical mass of women will indicate they could see themselves as running that place in the organization.

One explanation to why so few women express ambition is ritual modesty. Women have been consciously or unconsciously “advised” to not express their ambition. But a major new study of women in the workplace conducted by LeanIn.org and McKinsey & Co. belies that canard. After a survey of nearly 30,000 men and women in North American companies, they found that women and men are almost exactly equal in their ambition levels – 78% and 75% respectively. This shifts as the job gets bigger: 53% of men want to be a top executive but only 43% of women do (although that is more than 0%). The presence or absence of children for women is not the determiner of ambition.

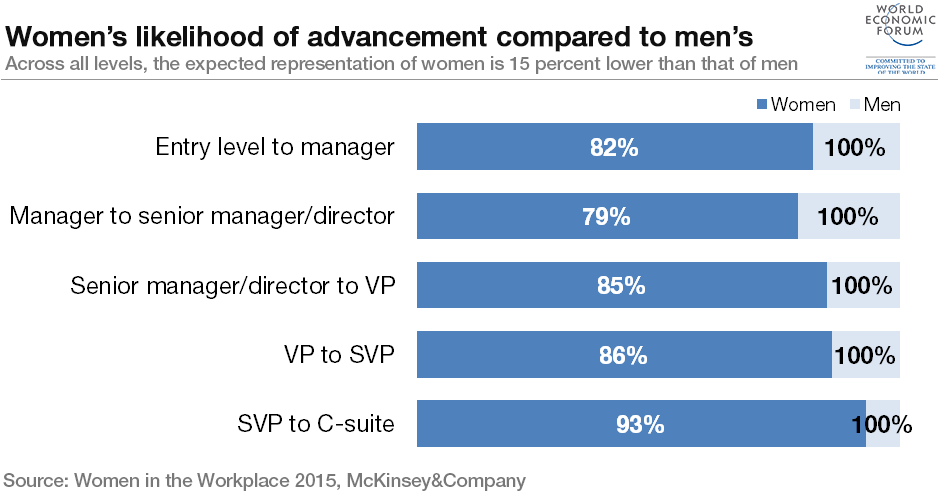

The result is what the World Economic Forum predicts: gender parity won’t be achieved until 2095, and 100 years for the C-suite. Imagine a United Nations Development Goal to eliminate poverty in 100 years. The world would find that unconscionable.

The top four causes of stress

Women feel that the path to leadership is disproportionately more stressful. Stress, and the perception of it, are accumulated over time. So what does this stress actually look like on a day-to-day basis for women? How do they experience it on any given work day?

- Being heard. Women express their ideas daily, in meetings, one-to-one conversations and emails just as men do, but they may do it differently and it may be received differently. Women have to constantly balance “how” they say things versus “what” they say.Often because of beliefs about what strong or angry women sound like, she must use some form of disarming mechanism such as ritual modesty, mitigation, apology, question, or a smile.It is like learning a second language – and like a second language, it can become second nature. Examples include: “I’m not the expert on this” or “I’m sorry but I guess we could just give this a thought” or “I’m not sure”. She is sure. She is the expert. She is not sorry. But she knows that making declarative statements will turn the listener (male) off and be dismissed because she is seen as too tough. The irony is that when she uses the disarming mechanism, she is not seen as capable.Women have a much narrower band of behaviour, on top of the fact that they may be interrupted much more than men and receive less affirmation for their comments. The point is that women make that speech calculation every day, with every interaction. Exhausting and stressful.Shelley Correll at Stanford University has found that men receive twice the positive feedback and four times more developmental feedback. Women are 66% more likely to be given a recommendation to change their communication styles. Stressful.

- Addressing Gender Folklore by State Street Center for Applied Research finds patterns of bias against women in the workplace. One of the patterns they call the “prove-it-again” problem. This is the tendency for women to face more requirements than men. In the diversity world, dominant groups are assumed to be competent until they prove they are incompetent. Non-dominant groups are assumed to be incompetent until they prove they are competent. It is like the movie Groundhog Day, with each day starting anew without benefit of any of the previous day’s accomplishments. For women, this means a constant need to show they can do the job versus a man’s need to only show over time that he cannot do the job. Women’s competency bank account grows much more slowly.Confirmation bias means a woman is over-scrutinized, so every slip or error “proves” her incompetence. One organization I worked with had a ranking system for reviews, with one being highest and four lowest. Men were assumed to be first or second quartile until they over time showed they were not. Women were assumed to be second or third quartile until they proved over time that they were first quartile. Stressful.

- Networks and sponsorship are key to advancement. Professor Herminia Ibarra of Insead has found that women are over-mentored and under-sponsored. Mentorship is highly useful at the lower levels in a hierarchy for career progress. At the highest levels, it is sponsorship that is crucial. Like will sponsor like more easily and with less risk than sponsoring someone who is not like them. For women, getting a sponsor is difficult and stressful.Aaron Dhir, a law professor in Toronto, published Challenging Boardroom Homogeneity in 2015. For the book he interviewed women and men in Norway who have now lived for 10 years under the 40% board-quota regime for women. Of his many findings, one of the most important was that the quota law forced the interruption of in-group favouritism and closed social networks that in the past had thwarted diversity. Dhir also found that the quota-induced gender diversity had positively affected boardroom work and governance processes. The board members, both men and women, emphasized the broader band of perspectives and experiences that women brought to the board, as well as the outsider status, which was seen as a plus. The observation was that women engaged to a greater degree in rigorous deliberations, risk evaluation and monitoring of the executives.The quota law provided a much less stressful way for women to access opportunities, and because of the critical mass of women there was no sense of marginalization for the women appointed.

- Other daily stressors for women might include who gets the good assignments or is seen as the go-to person. It might be the daily inclusions and exclusions, such as the bonding that comes from sports conversations, the evening drinks at the bar, the banter between two men. The World Economic Forum Gender Gap Report shows that women still do more housework and childcare than men in every country. This means that women free up men’s time and subsidize their ability to get to the more senior positions. Stresses like these may be seen as insignificant in each instance, but over time they accumulate to create a daily experience for women in the workplace that is substantially different than for men. That accumulation may have a chilling effect on a woman’s desire to play the corporate game in the face of a different set of rules and measures. It becomes too stressful and she concludes that the playing field is not level and therefore not a field she wants to play in.

The solutions may also need to be small interrupters than can have big effects. Bias interrupters are more and more available with the advent of data and people analytics. For example, a company has created socio-metric badges that can monitor people’s interactions in meetings. The badges measure total speaking time, overlapping speaking time, turn-taking, average length of speech, affirming gestures such as nodding or body language. For an unaware manager this can provide hard data on who gets interrupted, how long people speak, who does not get heard, who gets over-heard or under-heard. Managers can be taught how to level the playing field on a daily basis.

Assignment tracking can be measured. One company I worked with found with tracking that the men were getting the large-cap, heavy industries to evaluate and the women were more likely to get the medium and small-cap, service industries to evaluate. This made a difference in compensation and promotion criteria. They developed a fairer way of allocating assignments once they possessed this information.

Use of independent interlocutors during review evaluations can reduce the performance distortions. An independent observer can ask why a man who speaks his mind strongly is seen as visionary and a leader, while a woman who speaks her mind is seen as having sharp elbows.

We can look at the impact of inequality in the workplace at the macro level and understand the business case for gender parity. But to reduce the stress for women to succeed and attain the highest levels of leadership we need to start at the micro level. We need to understand what it is like to live day to day in the workplace. That is the place to start if we want less stress and more progress.

More from Laura Liswood

Video: 3 ways to get more women into power

How men and women see gender differently

Video: How to achieve gender parity

The Summit on the Global Agenda 2015 takes place in Abu Dhabi from 25-27 October

Author: Laura Liswood is Secretary-General of the Council of Women World Leaders. Member of the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Gender Parity.

Image: A woman uses her mobile phone at an office building in Tokyo July 21, 2015. REUTERS/Toru Hanai

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Future of Work

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Equity, Diversity and InclusionSee all

Marielle Anzelone and Georgia Silvera Seamans

October 31, 2025