What does climate justice look like?

Explore and monitor how Pakistan is affecting economies, industries and global issues

Stay up to date:

Pakistan

This article is published in collaboration with Project Syndicate.

It is a painful irony of climate change that those least responsible for the problem are often the most exposed to its ravages. And if any country can claim to be the victim of this climate injustice, it is Pakistan. As world leaders prepare to meet at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris, the country is reeling from the aftereffects of devastating floods that damaged buildings, destroyed crops, swept away bridges, and killed 238 people.

Such weather-related tragedies are not new to Pakistan; what’s different is their frequency and ferocity. Deadly floods have become a yearly occurrence; in 2010, record-breaking rains killed nearly 2,000 people and drove millions from their homes. Even as Pakistan fights one of the world’s most pitched battles against terrorism, increasingly violent weather is pushing up the cost of food and clean water, threatening energy supplies, undermining the economy, and posing a potent and costly security threat.

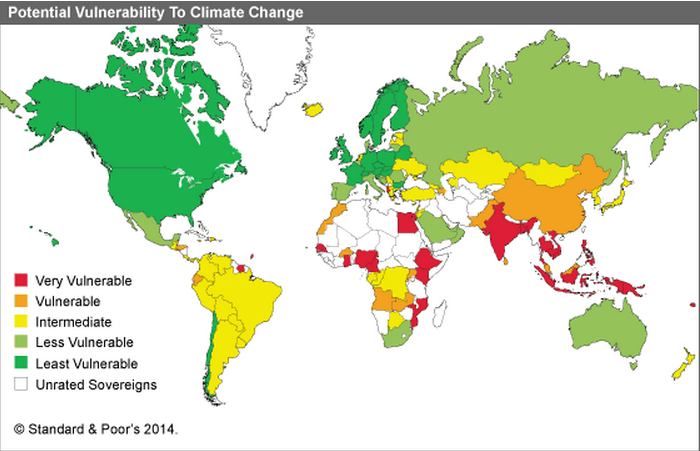

There is little doubt that the country’s climatic woes are caused, at least in part, by the greenhouse-gas emissions that industrialized countries have pumped into the air since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Even today, Pakistan produces less than 1% of the world’s emissions. Meanwhile, Pakistan is consistently ranked among the countries that are most vulnerable to the harmful effects of climate change, owing to its demographics, geography, and natural climatic conditions.

From 1994 to 2013, climate change cost Pakistan an average of $4 billion a year. By comparison, in 2012, terrorism in Pakistan resulted in losses of roughly $1 billion. When the country isn’t suffering from floods, it is subject to water shortages, ranking as one of the most water-stressed in the world, according to the Asian Development Bank. And climate change is compounding both problems, wearing away at the glaciers and snowpack that serve as natural regulators of water flow, even as increased erosion caused by flooding contributes to the siltation of major reservoirs.

Meanwhile, rising temperatures are increasing the likelihood of pests and crop diseases, jeopardizing agricultural productivity and subjecting the population to increasingly frequent heatwaves. Rising sea levels are increasing the salinity of coastal areas, damaging mangroves, and threatening fish species’ breeding grounds. And higher ocean temperatures are leading to more frequent and dangerous cyclones, endangering the country’s coast.

The outlook for the future is no less alarming: worsening water stress, increased flash flooding, and the depletion of the country’s water reservoirs. By 2040, projections indicate that an average rise in temperatures of 0.5º Celsius could destroy 8-10% of Pakistan’s crops.

This burden must not be left for Pakistan to carry alone. Thus far, progress at international climate-change talks has been incremental at best. Fossil-fuel lobbies, reluctant governments in industrialized countries, and disengaged electorates have delayed and obstructed the emergence of a robust agreement to reduce global greenhouse-gas emissions. But while expectations of a breakthrough in the fight against climate change in Paris are optimistic, a push for equitable distribution of the costs of global warming must be made.

Despite an increase in funding for climate adaptation and mitigation in the developing world, Pakistan’s share has remained tiny, relative to the disasters it has suffered in the last five years alone. By 2050, the average annual cost of climate-change adaptation in Pakistan will be $6-14 billion, according to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Mitigation will run another $17 billion per year.

As climate change continues to take its terrible toll, Pakistan cannot allow the billions of dollars in damages it suffers at the hands of the world’s largest polluters to go uncompensated. Whatever the ultimate agreement in Paris, climate negotiators must ensure that the accrued losses resulting from global emissions are borne fairly and do not remain the sole burden of those suffering the greatest harm.

As one of the world’s smaller polluters, Pakistan is well within its rights in seeking resources and funds to cope with the impact of problems for which it is not responsible. So are many other countries. Our demand for a binding international mechanism to distribute the burden of climate change – a mechanism to ensure climate justice – must not go unheeded in Paris.

Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Sherry Rehman is a senator, Vice President of the Pakistan People’s Party, and Chair of the Jinnah Institute.

Image: A flood victim carries a rubber ring as he arrives on dry land. REUTERS/Zohra Bensemra.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Climate ActionSee all

Jean-Claude Burgelman and Lily Linke

May 9, 2025

Tejashree Joshi

May 8, 2025

Tom Crowfoot

May 7, 2025

Nii Ahele Nunoo

May 6, 2025

Alfredo Giron

May 6, 2025

Denise Rotondo and Chris Leong

May 5, 2025