Will China change the world’s financial institutions?

Erik Berglof

Director, Institute of Global Affairs, School of Public Policy, London School of Economics & Political SciencesStay up to date:

China

This article is published in collaboration with Project Syndicate.

The board of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development recently approved China’s application to join – an application a decade in the making – and sent it on to member governments for final approval. But EBRD membership is only one expression of China’s rapidly growing role in the world’s international financial institutions. The question now is whether China will spur change within them, or vice versa.

The global financial crisis shook up the international financial architecture, catching many institutions off guard. The International Monetary Fund, for example, had actually pursued sharp downsizing in the preceding years. But it also allowed them to prove their mettle. Many of them – not least the IMF, but also the EBRD and the European Investment Bank – eventually showed that they could respond flexibly and, as a result, have gained expanded mandates and more capital.

The crisis also undermined the legitimacy of the G-7 – the countries at the root of the problem – while invigorating the G-20. Amid these transformations, China gained an opening to boost its global influence – one that it is determined to exploit, despite resistance from some corners. It plans to use its presidency of the G-20 in 2016, for example, to advance an ambitious agenda.

In fact, Chinese international engagement is now occurring on a scale and at a rate never seen before. China is a member of many multilateral institutions – including several regional players like the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) – with which it is deepening its relationships, especially through co-investment in projects around the world. For example, China significantly ratcheted up its commitment to the AfDB last year through the $2 billion Africa Growing Together Fund.

Similarly, China’s sovereign wealth funds have served as important anchor investors in the vehicles designed by the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation and the EBRD to bring long-term institutional capital into their projects. One of those funds, SAFE, is currently the only investor in the EBRD vehicle – and China has not even formally joined the organization yet.

China is also forging new institutions. The establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) captured global headlines earlier this year, not just because of strong US resistance, but also because countries like Britain and Germany joined anyway. China also played a leading role in the formation, with its BRICS counterparts (Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa), of the New Development Bank (NDB), now headquartered in Shanghai.

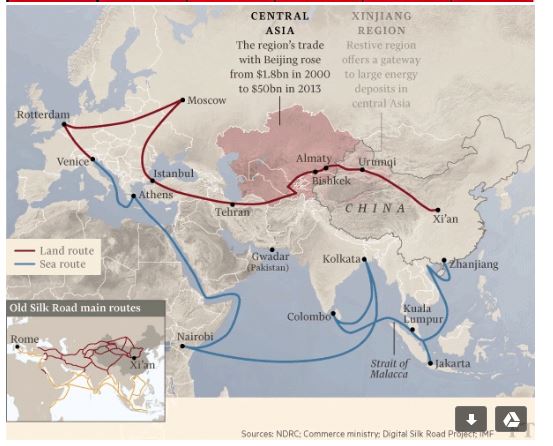

Then there is China’s $40 billion Silk Road Fund, intended to support the infrastructure projects needed to underpin President Xi Jinping’s “one belt, one road” strategy, which aims to improve trade and communication linkages across Eurasia. China’s most ambitious effort to date, the Silk Road Fund dwarfs the activities of the more traditional international financial institutions, in terms of both scale and range of activities. The Fund’s first initiative, the $1.65 billion Karot hydropower dam in Pakistan, will entail both direct lending to the project and equity investment in the company responsible for building the dam and managing it for 30 years.

As it stands, the Silk Road Fund is unilateral, placing it in the same category as the China Development Bank and the state-owned investment conglomerate CITIC. But the Chinese authorities have said that it is open for others to join, though that seems unlikely, given the scale of the Chinese commitment.

Despite the remarkable size of China’s investment projects, the country’s leaders have so far remained relatively conservative in terms of institutional innovation. Over the last year, however, Chinese Communist Party officials have mooted a proposal for a more experimental new multilateral financial institution geared toward “restoring the environment” – that is, supporting large projects aimed at land reclamation, water purification, and improvements in air quality.

Getting such an institution off the ground will not be easy, given the need for global coordination to bring potential shareholders together and for large subsidies to make investments viable. But that kind of bold institutional innovation could fill an important gap in the global financial architecture, and cement China’s leadership in financing environmental remediation.

In the meantime, Chinese institutions are innovating on a smaller scale, as they spearhead a leaner and faster approach to financing. For example, the AIIB’s inaugural president, Jin Liqun, has announced plans to eliminate some of the most inefficient features of existing institutions, like the resident board and nationality restrictions on hiring.

Nonetheless, China’s growing global financial role is not likely to change profoundly how existing institutions operate. Of course, as efforts like Jin’s highlight the flaws in existing structures, they may help to inspire reform. And the EBRD can undoubtedly benefit from China’s experience with experimentation and scaling up.

But the main aim of the AIIB and the NDB seems not to be to transform the multilateral financial landscape, but to add capacity, while showing that China can build state-of-the-art institutions. And when it comes to the EBRD, China’s stake will be tiny, at least at first; the Chinese say they are there to learn. Indeed, co-investment with the EBRD can provide Chinese companies with local knowledge – and potentially even protection – as they navigate new markets.

For now, increased engagement in multilateral institutions seems likely to change China more than it changes the institutions, even as China’s voting power increases to reflect better its growing contributions. A closer look at the experiences of long-standing institutions – including working with civil-society groups and promoting local ownership of policies – will help China hone its strategy for engagement in Africa and elsewhere. It may even enable China to improve its own development model.

In the longer term, however, the development challenges that China faces at home – particularly rapid environmental deterioration – could drive it to take a more transformative role, pushing for institutional innovation globally.

Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Erik Berglöf is a Professor and Director of the Institute of Global Affairs at the London School of Economics.

Image: A Chinese national flag flutters at the headquarters of a commercial bank on a financial street. REUTERS/Kim Kyung-Hoon.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Geographies in DepthSee all

Abdulwahed AlJanahi

March 3, 2025

Naoko Tochibayashi and Mizuho Ota

February 28, 2025

Sael Al Waary

February 27, 2025

Naoko Tochibayashi and Mizuho Ota

February 26, 2025

John Letzing

February 19, 2025

Cameron Munter and Jan Ruzicka

February 18, 2025