Can religion make economic growth more fair?

Rising income inequality contributes to social and political unrest, threatening our economic future and general wellbeing.

While it is clear that social problems will increase if economic growth benefits a small minority, there is very little concrete analysis of how different sectors of society contribute to the goal of inclusive growth. The need for better analysis is reflected in the World Economic Forum’s new programme to benchmark progress toward economic growth and social inclusion.

This blog is part of series on the way faith interacts with tough global challenges, from inclusive growth to gender parity to climate change.

Why is the faith factor important to consider? First, because religious adherence is on the rise, as is clearly seen in recent research on religious demographics.

Second, because religion is often ignored. In fact, religion plays both negative and positive roles in relation to inclusive growth. On the one hand, religion-related hostilities, prejudices and biases can lock people out and inhibit inclusive growth. On the other, religious organisations have a tremendous capacity for doing good, with most religious groups being known for their programs to address poverty and/or care for the poor (for example, earlier this year global religious and faith-based leaders convened at the World Bank to call for and commit to ending extreme poverty by 2030).

Beyond poverty alleviation, research also shows that when freedom of religion or belief (including interfaith and intercultural understanding) accompanies the rise of faith, the peaceful conditions necessary for inclusive growth are often strengthened.

The faith factor in inclusive growth is a complex topic which is only just beginning to be analysed. This post aims to help get the discussion started by offering a look at Christianity, while recognizing that other religions can also play an important role in inclusive growth. We invite specialists in other faith traditions to join the discussion. For instance, almsgiving, one of the five pillars of Islam, is widely practiced by Muslims worldwide according to a Pew Research survey of 38,000 Muslims.

“An economy that excludes kills”

“An economy that excludes kills.” With these words, Filipino Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagel, who was recently elected head of Caritas International, challenged business leaders in the Philippines to address poverty.

Speaking at the 39th annual Bishops-Businessmen’s Conference for Human Development, he exhorted them to include the poor in their vision and mission statements, in deciding what goods to produce and services to provide, and as part of their strategic plans.

Christian groups and organisations approach inclusive growth in a number of different ways, according to their different theologies. The largest Christian church, the Roman Catholic Church, emphasizes the importance of social justice and alleviating poverty.

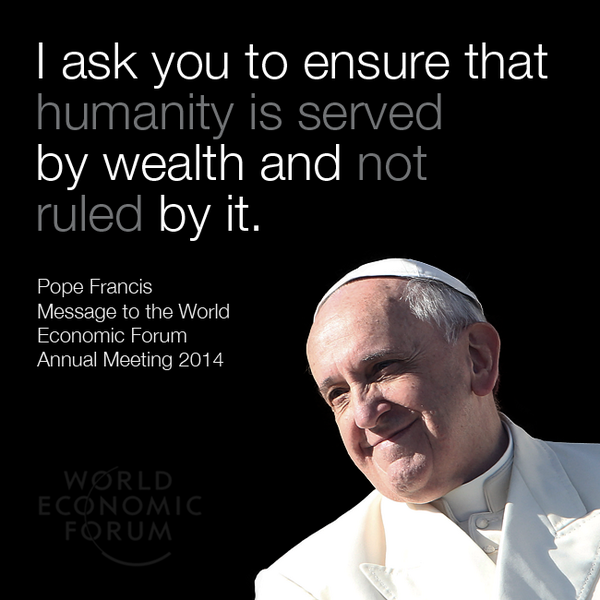

Meanwhile, Tagel was echoing the sentiment of Pope Francis. Speaking in Bolivia at the World Meeting of Popular Movements in July, the pontiff said that the first of three great tasks demanding decisive action is to “put the economy at the service of people. Human beings and nature must not be at the service of money. Let us say NO to an economy of exclusion and inequality, where money rules, rather than service. That economy kills. That economy excludes. That economy destroys Mother Earth.”

The other tasks he outlined were to unite all people on the path of peace and justice, and to defend the environment (see encyclical Laudato si’: On Care for Our Common Home).

“The dung of the devil”

This does not mean that the Catholic position is blindly pro-business. It is pro-people, and pro-business only to the extent that business can lift people from poverty and despair to prosperity and hope. Quoting a fourth century bishop, Pope Francis called the unfettered pursuit of money “the dung of the devil”, emphasizing that developing countries should not be reduced to providers of raw material and cheap labour for developed countries. The emphasis is on fair social distribution more than individual wealth creation.

Pope Francis and Cardinal Tagel are not alone among Christian leaders in focusing on social justice: many others champion inclusive growth, including Sojourner’s Jim Wallis and the Archbishop of Canterbury, while grassroots action also plays a key role.

The link between the protestant work ethic and capitalism

A second Christian approach, more typical of Protestant churches, places the emphasis on personal responsibility for wealth, prosperity, enterprise and growth.

Long ago the sociologist Max Weber noticed the connection between Protestantism and a “work ethic” which was central to capitalism.Today that lives on in new guises, ranging from an emphasis on hard work, self-reliance and strong families, to the “prosperity gospel”, particularly associated with Pentecostal Christianity (but also found in other religions). This asserts that if you have the right faith and proper religious practice, you will get rich, a theology which has some vocal critics within and outside Christianity.

Many church leaders grapple with the economic challenges on their doorstep. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which now has more members outside the United States (8.9 million) than it has in the U.S. (6.5 million), rolled out a global family self-reliance initiative, beginning in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin and South America. This helps church members and their families to find a job, start a business, or get the education they need to do one of these.

A third approach, which is even starting to have an influence on some forms of Pentecostal Christianity, is for churches, NGOs and other organisations to attempt to change both social structures and individual lives to ensure a better distribution of wealth. Increasingly, groups that once did charity are also doing advocacy. Ecumenical NGOs like Micah Challenge take this approach. They take the UN millennium goals seriously, and organize campaigns against problems such as corruption. They try to blend a “Catholic” emphasis on social justice and structural change with a “Protestant” focus on individual enterprise.

Christianity is shifting south

These changes are occurring as Christian populations are increasingly concentrated in the south, where the impact of poverty is more broadly felt. The share of the world’s Christians living in Europe is expected to decline substantially between 2010 and 2050. Meanwhile, the share of the world’s Christians living in Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to grow significantly from about 24% of the world’s Christians in 2010 to 38% in 2050.

The shift of Christianity’s centre of gravity to Africa means that the African experience will be a major factor in helping to shape the social and economic perspectives of global Christianity. And this process is already underway: there are more members of Anglican churches living in Africa than in England.

The president of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, which directly addresses issues related to poverty, is Cardinal Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson of Ghana. His council recently published a guide for business, Vocation of the Business Leader. On poverty, it states: “Developments in the field of the ‘bottom of the pyramid’ products and services—such as microenterprises, microcredit, social enterprises, and social investment funds—have played an important role in addressing the needs of the poor. These innovations will not only help lift people from extreme poverty but could spark their own creativity and entrepreneurship and contribute to launching a dynamic of development.”

“They know how to fish – they just can’t access the pond”

Faith-based thinking on poverty stemming from decades of experience in sub-Saharan Africa is rapidly moving beyond just delivering aid or “teaching a man to fish.” As Doug Seebeck, president of Partners Worldwide, a global Christian network aiming to end poverty, says, “They know how to fish!… People at the margins know how to fish, but they don’t have access to the pond. They aren’t able to engage and participate in the economic systems, markets, relationships, networks of support and collaboration and cooperation, tools, and models many of us take for granted.”

We have focused here on positive faith initiatives. But whether it works for good or ill, the role of religion and faith in promoting inclusive growth around the world needs to be taken seriously.

Authors: Brian Grim, President, Religious Freedom & Business Foundation; Linda Woodhead, Professor, Department of Politics, Philosophy & Religion, Lancaster University

Image: Pope Francis kisses a child as he visits the refugee camp of Saint Sauveur in the capital Bangui, Central African Republic, November 29, 2015. REUTERS/Stefano Rellandini

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Economic Growth

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.