How does Google’s quantum computer work?

If you thought a memory upgrade and clearing off some old photos was enough to bring your laptop up to speed, think again.

Google says its D-Wave 2x quantum computer, which it operates with NASA at the US Space Agency’s Ames Research Center in California, has been churning through complex algorithms at 100 million times the speed that a standard computer chip can manage.

That paves the way for faster solutions to big-data problems like cracking codes, cleaning up dirty data, and weather modelling, as well as raising the possibility of creating genuine artificial intelligence.

But Google’s announcement of the predicted next stage of computing hasn’t entirely avoided criticism. Some researchers point to Google’s own admissions that certain algorithms can be solved faster using conventional computer hardware, and current quantum computer builds are incredibly expensive pieces of equipment that won’t be available to the consumer market for years.

What is quantum computing?

The basic element of computing involves a yes/no switch called a “logic gate”. These gates can be in one position at a time – either on or off. A standard computer contains billions of these gates, all of which can switch between their on and off positions billions of times a second.

At any one time, however, these gates are only in one position. If you were to freeze time and take a look under the hood, you would find a specific combination of 1s and 0s across all of the gates. A standard computer has to sequentially explore all of the potential solutions to every algorithm it is presented with.

Honey I shrunk the logic gates

With quantum computing, the idea is that these logic gates can be in both states at the same time (known as a “superposition”), thereby solving complex algorithms simultaneously.

The secret lies in miniaturizing the logic gates until they are so small that classical physical laws break down and the realm of quantum physics (that of tiny things) takes over. These shrunken gates are known as “qubits”, and a quantum computer consisting of qubits would theoretically exist in all possible combinations of 1s and 0s at the same time.

In principle, that parallel processing power results in calculations being solved almost instantly – or at least many, many millions of times faster than conventional computers can manage.

How does this compare with the current fastest supercomputers?

In 2013, when D-Wave was tested against a top-of-the-range desktop computer running complex algorithms, the quantum computer produced 100 solutions in half a second. The state-of-the-art supercomputer it was up against required 30 minutes to produce the same.

That’s 3,600 times faster.

How long until we see a working quantum computer?

Microsoft suggest we could witness the first working hybrid quantum computer within the next decade. Stability and costs are two very big roadblocks at present; but for now, the focus is on getting the technology up and running in the first place.

Have you read?

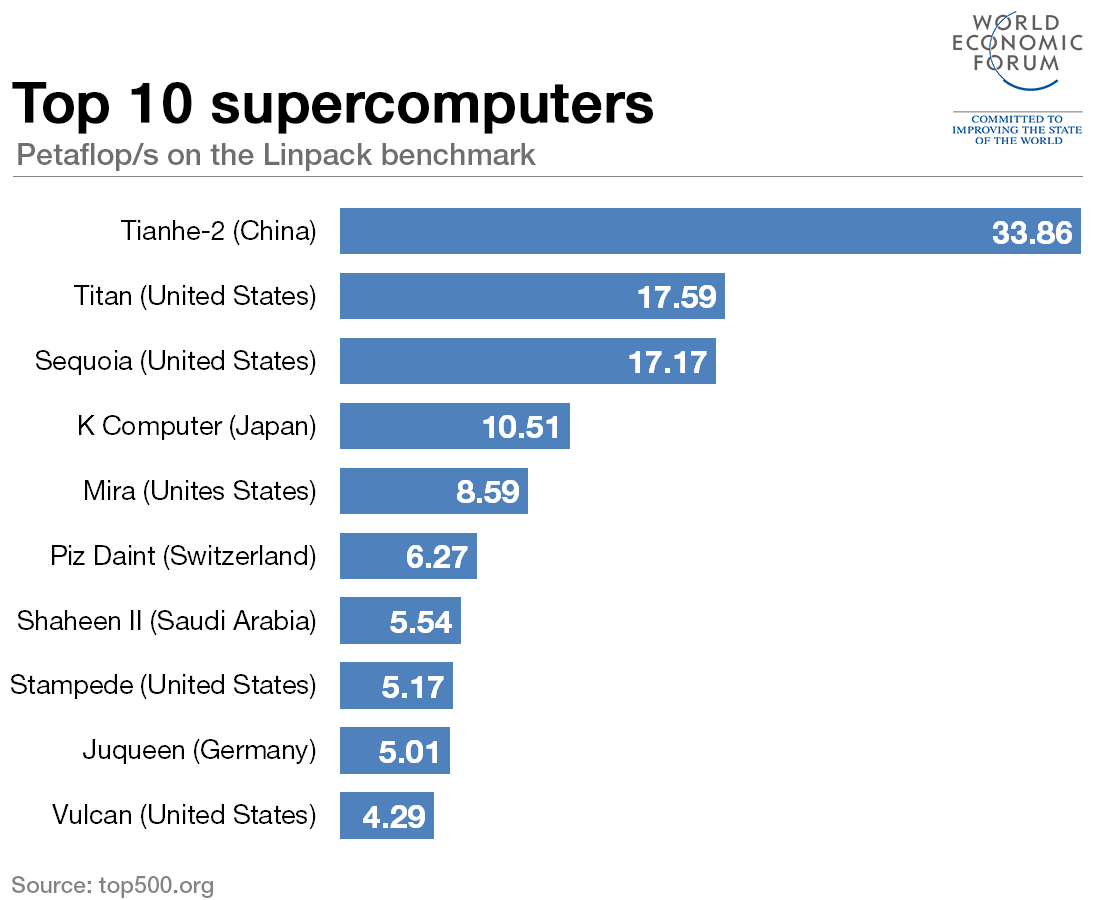

The 10 most powerful supercomputers

Artificial intelligence: can we manage the risk?

Will we be able to talk to computers?

Author: Henry Taylor is a social media producer at the World Economic Forum

Image: A D-Wave 2X quantum computer is pictured during a media tour of the Quantum Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (QuAIL) at NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California, December 8, 2015. REUTERS/Stephen Lam

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

The Digital Economy

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on InnovationSee all

Awais Ahmed and Srishti Bajpai

November 11, 2025