How will the US Federal Reserve actually raise the interest rate?

Stay up to date:

United States

This article first appeared on The Financial Times.

Related posts:

FT Explainer: Interpreting Fed funds futures

Economists forecast multiple US rate rises next year

The surprising links between Barbie and the Fed

Buckle up. On Wednesday, the Federal Reserve is expected to raise interest rates for the first time since 2006, and reversing the past seven years of extraordinary monetary policy looms as being an experimental, possibly bumpy lift-off.

When economists talk about the Fed’s official borrowing rate, they refer to the Fed funds rate, which since late 2008 has been confined to a corridor between zero and 0.25 per cent.

Here is a chart that shows the overnight Fed funds rate over the past decade. There were some loopy moves around the financial crisis, but generally the central bank has kept control of the rate.

The Fed funds rate sets a benchmark for the cost of credit that ripples through markets and guides borrowing costs for everyone in the US (and much further afield). But the Fed’s crisis-fighting has stymied the old-fashioned way of lifting interest rates.

Quantitative easing by the Fed entailed buying massive amounts of bonds from banks and crediting their accounts at the Fed with new money — so the financial system is now awash with surplus Fed funds.

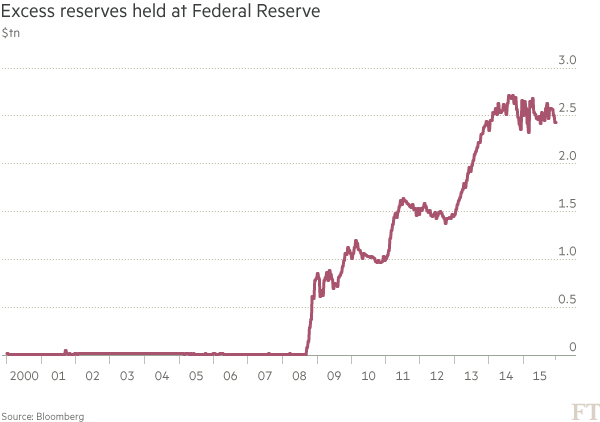

Here’s a chart that shows how the excess reserves, which pay 0.25 per cent to banks, have exploded in recent years. That little dimple in 2001 is when the Fed pumped extra money in the system following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The US central bank has maintained the effective Fed funds rate as its primary interest rate target at the upper end of a zero to 0.25 per cent corridor. Called “interest on excess reserves”, or IOER, this lets the Fed pay interest on money held at the central bank and when policymakers vote to lift interest rates, this IOER rate will presumably be lifted to 0.5 per cent.

In theory, this should drag the effective Fed funds rate up to this level, as banks should not be willing to lend to other financial institutions at a rate lower than what the central bank pays. But only actual banks have access to the IOER, and there are many other lenders in the Fed funds market that in practice have dragged the effective rate well below where the IOER is set.

Here’s a chart that shows that in action.

So the Fed has other new tools to help it manage the process of lifting rates. Acting as a floor for now at 0.05 per cent, the overnight reverse repo programme, or Overnight RRP , is primarily aimed at money market funds, and is expected to do much of the heavy lifting.

In a typical RRP the Fed’s market desk sells a Treasury bond from its portfolio to a money-market fund and agrees to buy it back the next day at a certain price, a process known as “repo”, short for repurchase. In practice, the central bank’s balance sheet does not shrink, but this sets a benchmark for cash interest rates paid by the Fed itself. These RRP operations will happen every business day between 12.45pm and 1.15pm in New York.

Here is a chart that shows how the Fed has been testing the impact of the RRP on the effective funds rate. It has occasionally been lifted or lowered to see the impact on the Fed funds market.

Currently the RRP programme is capped at $300bn to avoid the Fed’s operations distorting money markets, but economists expect its size to have to be expanded — possibly dramatically — to ensure that the central bank gets enough torque underneath its interest rate increase, at least in the short term. Most analysts predict it will have to be enlarged to $750bn to $1tn, or perhaps be unlimited in size to ensure a smooth lift-off.

Still, even if the Fed manages to get the effective Fed funds rate up to roughly the midpoint in its new corridor, the question remains whether the rest of the fixed income market will respond.

Typically, other important market rates would rise alongside the Fed funds, as banks and fund managers took advantage of any opportunities to “arbitrage” away anomalies. But regulations have severely curtailed the ability of banks to lubricate these arbitrage trades, leading to a series of anomalies in money markets.

For example, the GCF bank repo rate — essentially the cost for banks to borrow from each other when they proffer collateral like Treasuries — is now markedly higher than Libor, the unsecured bank funding rate.

Some economists argue that the Fed should look for a new mechanism to set US interest rates, since the Fed funds market is so small and thinly traded nowadays. There used to be close to $350bn a day that changed hands before the crisis, but daily volumes are now roughly $50bn a day. Some are therefore urging a radical rethink.

Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: The Financial Times covers, comments and analyses the latest UK and international business, finance, economic and political news.

Image: The United States Federal Reserve Board building is shown in Washington. REUTERS/Gary Cameron.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Financial and Monetary SystemsSee all

Ekhosuehi Iyahen, Daniel Murphy and Andre Belelieu

August 27, 2025

Tariq Bin Hendi

August 26, 2025

David Ebube Nwachukwu and Adam Skali

August 25, 2025

Lim Chow-Kiat

August 21, 2025

Dalal Buhejji

August 14, 2025

Hallie Spear

August 13, 2025