What’s happened to America’s middle class?

This article is published in collaboration with Wonk Blog.

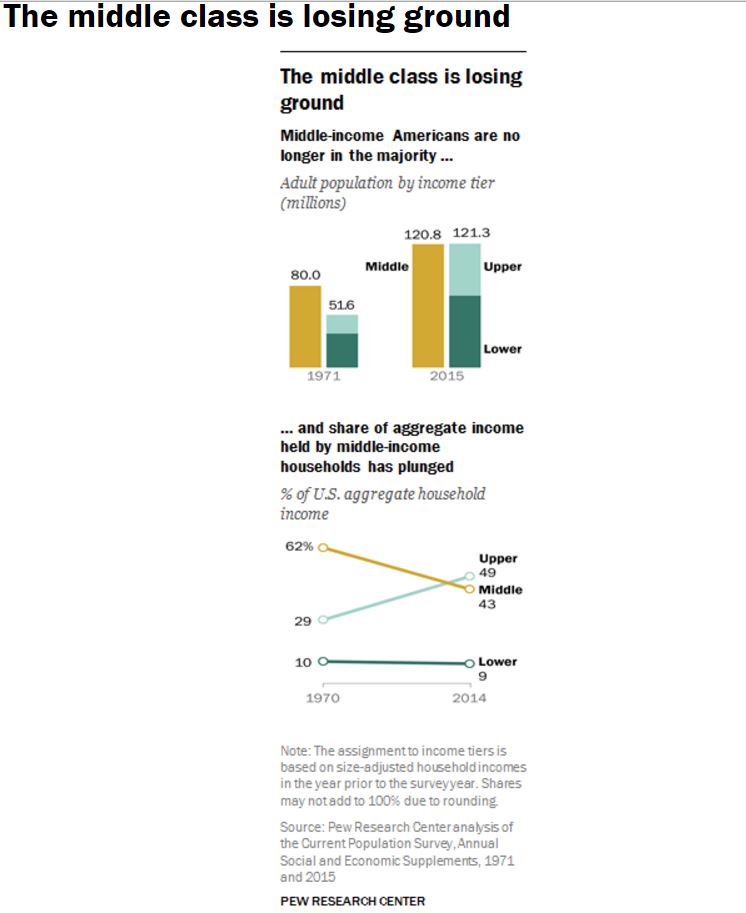

After more than four decades of economic realignment and creeping inequality, the U.S. middle class is no longer the nation’s majority.

The number of households that are middle class is now matched by those that are either upper or lower income, according to a report released Wednesday by the Pew Research Center.

The nation has arrived at this tipping point in part because more Americans are moving up the income ladder. In 1971, just 14 percent of Americans were in the upper income tier, which Pew defined as more than double the nation’s median income. Now, 21 percent of American households are in that upper earning category — at least $126,000 a year for a three-person household.

But at the same time, many Americans are falling behind, helping to deplete the middle. In 1971, a quarter of American households fell into the bottom earning tier, which Pew defined as less than two-thirds of the nation’s median income. By 2015, 29 percent of American households fell into that category, which for a three-person household meant they earned $42,000 a year or less.

Overall, the share of Americans living in middle-class households has declined from 61 percent in 1971 to 50 percent. The hollowing out of the middle class has been a source of consternation among many economists, politicians and the public at large. They say as Americans move toward the economic extremes it is harder to find common ground, and a common sense of what it means to be an American.

But others say a shrinking middle class–however that group is defined–is not problematic by itself.

“I don’t think it is anything we should be worried about,” said Scott Winship, a senior fellow at the conservative-leaning Manhattan Institute. “More important than how many people are in certain income ranges, is whether people are moving up.”

The decline of the middle class has been accompanied by growing inequality, as a growing share of the nation’s income has been captured by those at the top. Nearly half of the nation’s aggregate income went to upper-income households in 2014, the report said, up from 29 percent in 2014. Meanwhile, those in the middle earned 43 percent of the nation’s income in 2014, down from 62 percent in 1970.

That trend has only accelerated since the turn of the century. Median income for middle income families declined 4 percent between 2000 and 2014, and their median wealth, decimated by the Great Recession, cratered by 28 percent between 2001 and 2013, the report said.

[The American middle class is worse off compared to others around the world]

The slimming of the middle class has come even as Americans of all income levels have grown more prosperous, Pew found. Middle class families have seen their income grow by 34 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars since 1970, while lower-income Americans have experienced income growth of 28 percent. Still, that growth is not nearly as strong as the 47 percent income growth experienced by upper-income households in that time period.

The changing economic fortunes of American households has been most dramatic at the far ends of the income spectrum, Pew found. The share of households earning more than three times the median income–$188,000 a year for a family of three in 2014 dollars–is now 9 percent, up from just 4 percent in 1971. At the bottom, one in five households earned less than half the overall median income–$31,000 a year in 2014–up from 16 percent in 1971.

The report also found that older Americans, married couples and black Americans have made more economic gains than others in recent decades. Between 1971 and 2015, for example, the share of black Americans in the upper income tier more than doubled to 12 percent. Meanwhile, some 17 percent of adults aged 65 and older are in the upper income tier, Pew said, up from just 7 percent in 1971.

Despite that progress, African Americans and the elderly still remain more likely than other Americans to be lower income, and less likely to be higher-income.

One marker of relative prosperity in recent decades has been educational achievement. While the economic status of Americans with bachelor’s degrees changed little from 1971 to 2015, those who did not graduate from college fell down the income ladder.

That shift was magnified by evolving social trends, which saw marriage in decline overall, but especially for those with fewer educational credentials. Married adults have moved up the income ladder over the past four decades, while those who are unmarried slipped backwards, the report said.

Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Michael A. Fletcher is a national economics correspondent, writing about unemployment, state and municipal debt, the evolving job market and the auto industry.

Image: Morning commuters are seen outside the New York Stock Exchange. REUTERS/Brendan McDermid.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Economic Progress

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Council on the Future of Growth and 2023-2024

December 20, 2024