A tale of two feminisms at Davos

"The workplace still simply does not make room for care"

Image: REUTERS/Mario Anzuonia

Stay up to date:

Future of Work

Every year the World Economic Forum laments the lack of women in top corporate ranks; the number of women attending has never broken 20%, notwithstanding strenuous efforts by the Forum itself to create incentives for participants to add women to their delegations. Many sessions focus on women, work, and family; female leadership and mentorship; and the global education and promotion of women and girls. This emphasis reflects the Forum’s ongoing work on gender parity as a global challenge.

These efforts are important. As Sheryl Sandberg, Adam Grant, Mahzarin Banaji, and many others have demonstrated, unconscious bias runs rampant in offices, in men and indeed often women. Deep assumptions about who women are and what leadership looks like often leads management to have less confidence in women than in men; those same assumptions can also sap confidence among women themselves.

Do women really opt out - or are they pushed?

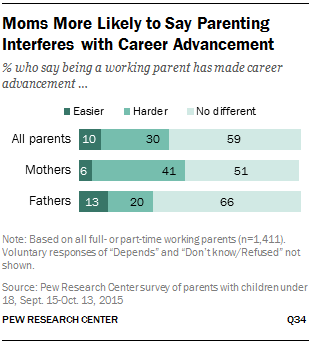

A second approach to advancing women focuses on the radical imbalance between breadwinning and caregiving. Well over 50% of women in OECD countries are breadwinners, but a tiny percentage of men are caregivers. Among American parents, mothers spend roughly twice as much time as fathers on childcare. And having a daughter is a predictor of avoiding being in a nursing home. That means that most working women are trying to hold down two full-time jobs while competing with men who have the luxury of focusing on only one. Even when husbands “help,” the responsibility of managing and directing the work that needs to be done still falls to wives. But the workplace still simply does not make room for care – of children, parents, or sick or disabled family members. As sociologist Pamela Stone puts it, women are less likely to “opt out” than to be “shut out,” denied the flexibility and part-time arrangements they often need to be both the parents and the professionals they want to be.

These two feminisms – call them confidence feminism and care feminism – are complementary. Both are needed to achieve actual equality between men and women in the developed countries. (In developing countries it is still necessary to start at a much more basic level, providing women with equal legal rights, the ability to plan the size of and timing of their families, and the education and training to earn their own livings.) Either one alone will fall short. It is much cheaper, however, to embrace confidence feminism, through special bias training, women’s groups, and mentorship programs, than care feminism, which requires much more extensive and expensive changes in the way we work.

Making room for care in the workplace requires assuming that all workers are or will be caregivers at some point in their working lives. It means assuming that when workers have or adopt children, both men and women will need parental leave to care for and bond with their infants or new family members and family leave at various points to meet their children’s needs as they grow. It means assuming that when elderly parents need care, both men and women will need flexibility and family leave to support them and simply spend time with them. It means assuming that some members of any workforce will have the misfortune of having a loved one with a serious illness and will need support and flexibility to care for that person. And it means treating workers who do take time for care equally with those who do not, cultivating their talents and providing them with the same leadership opportunities as their peers, even if on a slower track. Workers who do not have caregiving responsibilities can advance faster or take advantage of flexible hours and time off for self-care.

What the US Navy can teach us about retaining talented women

Other ways of tapping the talent of workers who are both breadwinners and caregivers include allowing and indeed inviting job-shares, a way of providing full-time coverage for a client or project with half-time workers. Or creating sabbatical or leave programs. The U.S. Navy, for instance, has a “career intermission” program designed to retain highly trained personnel by allowing selected service members to make a transition from active duty to the reserves for a period of up to three years, with a means for "seamless return to active duty."

The military invests an enormous amount in training their people; they understand that losing women is losing an investment. Athletes reach peak performance through interval training; why shouldn’t we look at careers the same way, with intervals of intense work and intervals of work combined with care or care alone.

On a more routine basis, Cynthia Calvert of Workforce 21C recommends that all managers develop “work coverage plans” identifying workers and teams that can cover a colleague’s workload if and when that colleague is out for an extended period. Good corporate practice routinely requires top managers at least to have succession plans, identifying who in the ranks would take over if the boss is hit by a bus. Planning for the inevitable but unpredictable rhythms of human reproduction, growing, aging and dying should be equally routine.

Why we need to disrupt the workplace

These kinds of changes, however, cost money up front, even if the investment will be roundly recouped in retention and attraction of talent. The cost of churn – the disruption of the workplace, the difficulty of hiring, loss of time and opportunity while new people get up to speed, and the loss of the investment in the hiring and cultivating of talented people – is enormous, even if hard to measure.

Equally expensive, however, is the cost of change – disruption of established ways of working. Harvard Business School Professor Robin Ely, who has conducted extensive research on why firms lose talent – both female and male – describes an intense resistance to the changes that she and many of her fellow consultants recommend: a rethinking about what good work is, where and when it needs to be done, and how to value performance over presence. Adopting policies aimed at helping women can be done on the margin. Changing work practices for everyone is much harder.

Here’s a different lens. Another perennial at the World Economic Forum are sessions on innovation, creativity, and risk-taking. Why not view disrupting the workplace with the same enthusiasm we embrace disrupting the hotel, taxi, or professional services businesses? Call it innovation for life, for women and men alike. Let’s give them the confidence to advance themselves and the ability to care for each other.

Author: Anne-Marie Slaughter is the President and CEO of New America, a think tank. She is participating in the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in Davos.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Forum InstitutionalSee all

Victoria Masterson, Stephen Hall and Madeleine North

March 25, 2025

Lorez Qehaja

March 19, 2025

Madeleine North

January 28, 2025