What’s the future of virtual reality?

Stay up to date:

Emerging Technologies

This article is published in collaboration with The Financial Times.

It could take a decade before virtual reality headsets become cheap and portable enough to replace smartphones as the tech industry’s dominant computing platform, the founder of Oculus VR has warned.

Virtual reality is tipped to be one of the biggest themes of this week’s Consumer Electronics Show, with Sony, HTC and Facebook-owned Oculus all set to release their headsets in the first half of 2016.

However, Palmer Luckey, who founded Oculus from his parents’ garage in 2012, has told the FT that the technology required many years of further development before it could “replace smartphones” for mainstream users.

“I think until you have really high-end computing power and until you have really slim form factors, you’re not going to see glasses that people wear every day as part of their everyday lives,” Mr Luckey said. “The only way we’re going to get to billions of users is if VR becomes something that everybody wants to use. And I think to do that, you’re going to [need to] get the cost way down and the quality way up.”

Asked how long that might take, Mr Luckey said: “It could be five years — it’s more likely to be 10 years. But I also don’t think that virtual reality has to get to a slim pair of glasses to be successful.”

In part, more development is necessary to reduce the risk of a social backlash akin to that suffered by Google Glass, Mr Luckey admitted.

“I’m not going to pretend that there won’t be an issue, there will always be people who are against these types of things,” he said, acknowledging that the current headset design is “obviously not the ideal form factor”. “As it goes from a bulky pair of goggles to a slim pair of glasses, you’re going to have a much different reaction to this type of thing.”

He added: “In the long run, the utility and adoption will outstrip any fashion concerns.”

Oculus announced on Monday that it would begin taking pre-orders for the Rift on January 6. Mr Luckey tweeted that shipping would “start” in the first quarter of 2016. The company has not yet revealed pricing for the first version of its Rift headset but Mr Luckey says it will initially be a “significant investment” that “disproportionately” appeals to videogamers and other early adopters in its first years on the market.

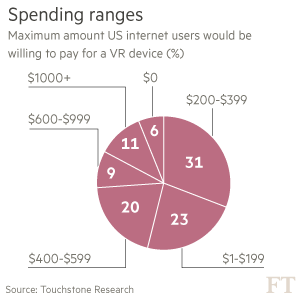

Mr Luckey said a VR system will probably cost a total of $1,500, including the headset and a PC powerful enough to run its high-resolution graphics fast enough to maintain the illusion of virtual worlds. Even then, the Rift’s cost is being subsidised to make it more affordable, as Facebook and Oculus try to establish the market for VR, Mr Luckey has said.

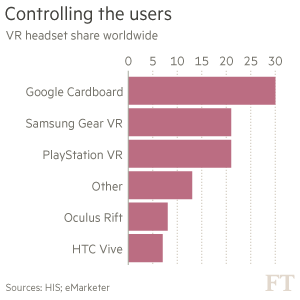

In December, Oculus and Samsung released the more affordable Gear VR headset, which uses a recent Galaxy smartphone for its screen and processor, instead of tethering to a PC. The $99 accessory is seen as a key way for newcomers to try out VR for the first time.

“Gear VR is very cool because it’s this portable experience that you can take anywhere,” Mr Luckey told the FT at November’s Dublin Web Summit.

“But the quality of the graphics are definitely much lower quality than what you get on a high-end PC. Obviously, we can’t wear a desktop PC on our head today so the question is; how long will it be before the chips that can render these VR worlds become small enough, low power enough, and low thermal density enough, that we can actually build them into a pair of glasses?”

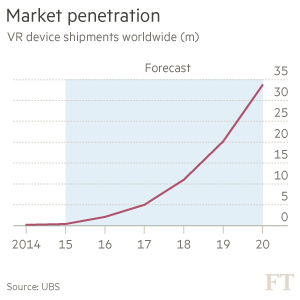

Three years after Oculus raised $2.4m in a Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign that launched VR back into the tech industry’s agenda for the first time since the 1990s, hype is building about VR’s growing presence at the International CES conference in Las Vegas.

“2016 is poised to be the year that consumer awareness of virtual reality reaches meaningful levels,” said Ben Wood, analyst at CCS Insight.

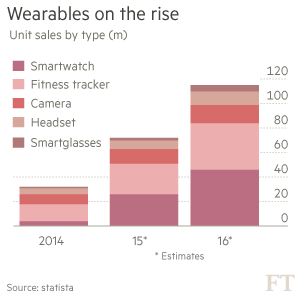

“As smartwatches continue to be a solution looking for a problem, attention [in the tech industry] is quickly turning to virtual reality as the next hot area for new revenue growth as smartphone sales slow,” Mr Wood said. “The big investments being made by the likes of Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Samsung and Sony underline the huge momentum around virtual and augmented reality right now.”

Analysts at IHS have predicted that Oculus Rift will initially sell in limited numbers and probably be outpaced by Sony’s PlayStation VR, which will have a larger number of customers with hardware that can support the headset. Nonetheless, that does not seem to worry Mr Luckey.

“Virtual reality doesn’t need to get to billions of people to be successful,” he said.

“I’d say that virtual reality doesn’t even need to sell hundreds of millions of units to be successful in this first generation.”

Oculus has said in recent weeks that it will bundle two titles, spaceship flying game Eve Valkyrie and cartoony platformer Lucky’s Tale, with every Rift headset it sells. But questions remain about what, beyond games, will help VR to appeal to mainstream users.

Mr Luckey said that while Facebook was working closely with its Oculus subsidiary, “nobody really believes that Facebook the social networking application is necessarily the killer app for VR”. Instead, new apps must be “designed from the ground up” for VR. However, VR will disrupt today’s social and communication services such as Skype or text messaging, he predicted, eventually reducing the need for face-to-face meetings and the accompanying environmental impact of physical travel.

“Virtual reality is the only technology that’s able to make you feel like you’re with another person in a virtual space, even if you’re thousands of miles apart,” Mr Luckey said. “If you could actually simulate anything you could possibly do in real life, plus not have to abide by the physical laws of reality, it seems incredible to me that you would not be able to come up with not just one killer app but many, many killer apps.”

Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Authors: Tim Bradshaw is a technology reporter for The Financial Times. Murad Ahmed is a European technology correspondent for the Financial Times.

Image: A visitor tastes food using Tasteworks technology, a Virtual Reality experience. REUTERS/Edgar Su.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Emerging TechnologiesSee all

Anurag Sinha

May 9, 2025

Jake Okechukwu Effoduh

May 7, 2025

Ti Hwei How

May 7, 2025

Adam Skali and Clementina Colombo

May 5, 2025