This is what girls in conflict zones get instead of education

Education is systematically ignored in situations of humanitarian crisis, and adolescent girls suffer from this the most. Image: REUTERS/Thomas Mukoya

Education is life-changing for children and young people, but the power of education is systematically ignored in situations of humanitarian crisis – and never more than at present. This neglect is reflected in the tiny amount allocated to children’s schooling in humanitarian responses: it involves only 2% of humanitarian funding. This neglect affects the lives of a generation of children and young people forever – once their education is disrupted it can never be retrieved.

Progress towards recognising education as part of a humanitarian response has been slow and the crisis has been worsening – resulting in millions more children and young people who are missing chance to go to school. There are now more displaced people than ever before – and around half of refugees are children.

And while the media is focused on the plight of families whose lives have been ruined by conflict in Syria, in other parts of the world millions of people have spent many years away from home. Dadaab, in northern Kenya, is the world largest refugee camp and has been in existence for more than 23 years. Strikingly, there are more than 10,000 third-generation refugees in Dadaab, born to parents who were also born in the camps. Yet, while inhabitants of the camps see the importance of education as the only thing they can take home, until recently there were no secondary school opportunities for the vast majority of young people there.

The World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul must be a turning point in giving prominence to education for those caught up in conflict for the sake of this and future generations of children and young people.

Adolescent girls suffer most

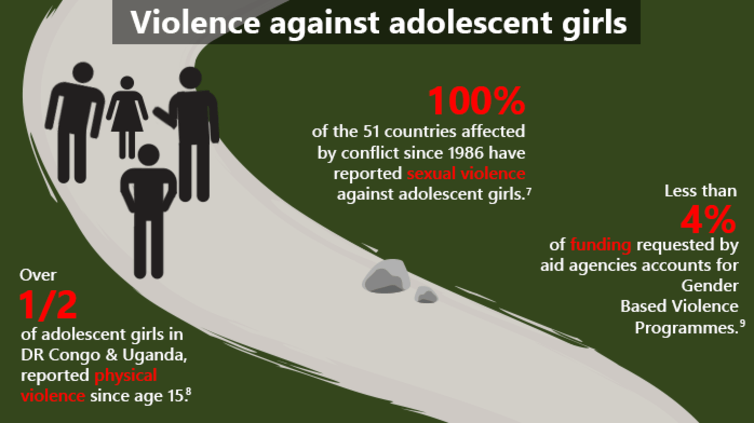

Adolescent girls' education journeys are being blocked in four key ways, as our new infographic shows. First, with just 13% of the extremely small pot of UNHCR education funding allocated to secondary schooling, it is no surprise that just 4% of the poorest girls in conflict affected areas complete secondary school. As a result, adolescent girls in conflict zones are 90% more likely to be out of school than elsewhere.

These girls are not only invisible casualties – they also often become targets. Unsafe journeys to school and direct attacks on school buildings mean that for many girls, most famously Malala Yousafzai, fulfilling their right to go to schooling means risking their lives.

Not only have attacks on schools increased 17-fold between 2000 and 2014, but there have been three times as many attacks on girls’ schools than boys’ schools in recent years. It takes just one day to destroy a school, but will take years to rebuild. In Syria alone 25% of schools have been destroyed, damaged or occupied since the conflict started.

Even their journeys to school place young girls at risk of physical and sexual violence. More than half of adolescent girls in the Democratic Republic of Congo report experiencing physical violence. And while all the 51 countries affected by conflict since 1985 have reportedsexual violence cases against adolescent girls, less than 4% of the funding requested by aid agencies accounts for programmes to tackle gender-based violence. In these situations, saving lives is inseparable from changing lives through education.

Limited opportunities

Early marriage is also a frequent alternative to education in contexts of severely limited opportunities and unsafe journeys to school. More than half of the 30 countries with the highest rate of child marriage are fragile or affected by conflict. And the transitions can be sudden – there were 18 times more early marriages among Syrian refugees in Jordan in 2013 compared with 2011.

A lack of education can also result in girls being recruited to fight in armed forces. While figures are hard to come by, on one estimate, around 40% of child soldiers are young women. Once recruited, their lives are disposable, three-quarters of suicide bombers in some West African countries have been identified as young women. And military and terrorist organisations abduct young women: in Chibok, northern Nigeria, Boko Haram abducted at least 276 girls – at least 219 of them are still missing.

Girls as child soldiers.Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge,Author providedEducation cannot wait

There is an urgent need to remove the obstacles facing adolescent girls on their journey to school. The shocking statistics presented here provide clear evidence of a problem that can no longer be ignored. Facing up to the problem needs to be accompanied by taking action.

The launch of the Education Cannot Wait Fund at the World Humanitarian Summit next week is a golden opportunity for world leaders to show their commitment to transforming the lives of children and young people for the future.

But realising change is not just about grand gestures at world summits. As commitments we have made together with others as part of the US First Lady’s Let Girls’ Learn Initiativehighlight, change has to happen on the ground. Changing journeys of adolescent girls requires working together with communities to ensure they finally get the education they deserve.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Education

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Education and SkillsSee all

Sonia Ben Jaafar

November 22, 2024