Our oceans keep us alive. Here's how we can stop killing them

Sylvia Earle: 'Take a look at all the plastic you use in your life, and what you could substitute it with'

Image: REUTERS/David Gray

Stay up to date:

Future of the Environment

They produce more than half the world’s oxygen, create more than $128 billion in GDP annually, and hold 97% of the world’s water. Oceans are our lifeline. And yet we know so little about them.

“More than 500 people have visited space, but just a handful have visited the deepest parts of the ocean. It’s been said that we know more about the surface of the moon than we do the ocean floor,” says Anisa Kamadoli Costa of Tiffany & Co, a leader in the business world when it comes to oceans advocacy.

Perhaps it’s this lack of awareness that explains how we’ve managed to do so much damage to the sea in such a short space of time.

“We used to think that the ocean was too big to fail, too vast for humans to have an impact upon,” legendary oceanographer Sylvia Earle told us. “We know now that isn’t the case. Oceans – our life support system – are being impacted in very significant ways.”

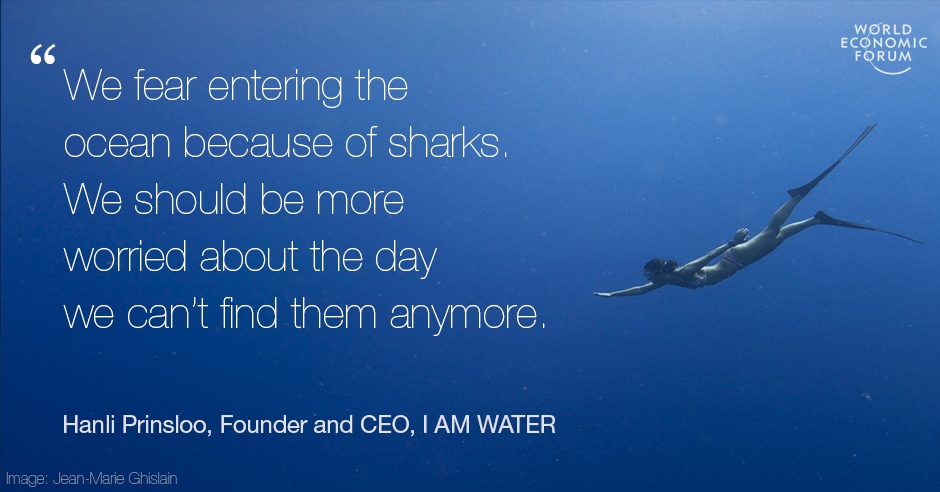

Another oceans advocate, Hanli Prinsloo, is not even 40 years old but has already seen irreversible changes to the world’s largest ecosystem. “What scares me more than anything is returning to places where an animal has always been, and finding it completely empty.”

That’s what happened when she went diving recently in the Red Sea. Formerly a hotspot for oceanic whitetip sharks – a near-threatened species – she found it completely deserted. “For two weeks, we waited and searched: nothing. I still consider myself to be quite young, yet in my lifetime I have seen a decrease in the creatures I have come to call friends. We fear entering the ocean because of sharks. But we should be more worried about the day we can’t find them there anymore.”

Others working in the field, such as WWF’s director of the Marine programme, John Tanzer, say they are starting to see change. “The momentum is building to reverse the unsustainable approach we’ve taken to the ocean for the past 150 years,” he said.

The good news? We can all do our part. “Everyone has the power to do something and, collectively, these actions can lead to a big and positive impact for our oceans,” Earle says. Even small changes can make a difference. “Take a good look at all the plastic you’re using in your life, and think about what you could substitute it with. Instead of plastic straws, use paper ones. Use a stainless steel reusable water bottle. The next time you get a meal to go, bring your own container.”

Even closer to home, think about what you’re putting in your body, Earle advises. “When we pollute our oceans, contamination, heavy metals and more travel up the food chain and back to us, especially when we eat large, old fish.”

So before you eat seafood, do your homework, just like we now do with our red meat or eggs. “So many countries – the UK, the US, South Africa, for example – have apps or websites where you can find out what is OK to eat,” Prinsloo says. “Get to know your fish!”

If that sounds like hard work, remember that being an oceans advocate can also be fun. “There are some really cool products out there that are turning ocean waste into products, which is also helping to educate the buyer. Some of my favourite examples are bikinis made from fishing nets and yoga pants made from plastic bottles,” says Prinsloo.

Soon, Costa points out, customers will even be able to buy running shoes made from ocean waste material. “These innovations are not only providing much-needed solutions, they’re also encouraging both companies and customers to consider their impact on the environment, and the difference their choices can make,” she notes.

But innovations, while critical, should not detract from taking action based on what we already know, says Tanzer. “We shouldn’t pin all our hopes on the ‘silver bullets’ of new technology.” The fact is, we already know what we have to do to protect our oceans. We just need to start doing it. “We know how to minimize pollution, how to manage fisheries more sustainably, and how to manage networks of protected areas. If we know what we have to do, let’s get on with implementing it.”

Companies like Tiffany & Co have been doing exactly that. “We don’t believe there’s a sustainable means of harvesting coral – it isn’t a plant or a rock, it’s a living creature, the nursery of our oceans. So a decade ago we just stopped using it, and have called on other jewellers to do the same,” Costa says.

It’s actions like these that show it’s not too late for our oceans, Earle says. “There are still so many reasons for hope. We have learned more about the oceans in the past 50 years than in all preceding history. Now that we know, we must act.”

Have you read?

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Nature and BiodiversitySee all

Elizabeth Mills

April 17, 2025

Tom Crowfoot

April 17, 2025

Lindsey Ricker and Hanh Nguyen

April 16, 2025

Alejandra Arochas and Constanza Torres

April 15, 2025

Kathlyn Tan

April 15, 2025