The Black Lives Matter movement explained

New Yorkers take to the streets in protest against the police killing of two black men, in July

Image: REUTERS/Darren Ornitz

Alem Tedeneke

Media Lead, Canada, Latin America and Sustainable Development Goals, World Economic ForumStay up to date:

United States

Following high-profile police killings of black men in Baton Rouge and Minneapolis, fatal attacks on officers by anti-police gunmen – and more recently protests in North Carolina after the police shooting of Keith Scott, a black man – the United States is being forced to confront its deep-rooted problems with race and inequality.

A strong narrative is emerging from these tragedies of racially motivated targeting of black Americans by the police force. It is backed up by a new report on the city of Baltimore by the Department of Justice, which has found that black residents of low-income neighbourhoods are more likely to be stopped and searched by police officers, even if white residents are statistically more likely to be caught carrying guns and drugs.

In the background, a campaign called Black Lives Matter celebrated its third anniversary. The movement, perhaps best known by its hashtag #BlackLivesMatter, grew in protest against police killings of black people in the United States. It has now crossed the Atlantic, with events and rallies held in the United Kingdom.

What is Black Lives Matter?

The movement was born in 2013, after the man who shot and killed an unarmed black teenager, Trayvon Martin, was cleared of his murder. A Californian activist, Alicia Garza, responded to the jury’s decision on Facebook with a post that ended: “Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.” The hashtag was born, and continued to grow in prominence with each new incident and protest.

The formal organization that sprung from the protests started with the goal of highlighting the disproportionate number of incidences in which a police officer killed a member of the black community. But it soon gained international recognition, after the death of Michael Brown in Missouri a year later.

Black Lives Matter now describes itself as a “chapter-based national organization working for the validity of black life”. It has developed to include the issues of black women and LGBT communities, undocumented black people and black people with disabilities.

Misleading numbers

According to this article in the Washington Post, 1,502 people have been shot and killed by on-duty police officers since the beginning of 2015. A cursory glance at the numbers reveals nothing to indicate racial bias: 732 of the victims were white and 381 were black (382 were of another race).

In fact, on the surface, these figures suggest it’s more likely for a white person to be shot by a police officer than a black person. But proportionally speaking, this isn’t the case.

Almost half of the victims of police shootings in the US are white, but then, white people make up 62% of the American population. Black people, on the other hand, make up only 13% of the US population – yet 24% of all the people killed by the police are black.

Furthermore, 32% of these black victims were unarmed when they were killed. That’s twice the number of unarmed white people to die at the hands of the police.

After adjusting for population percentage, this is the picture: black Americans are two and a half times more likely than white Americans to be shot and killed by police officers.

However, we have to count for distortion of the data, for various reasons. Firstly, it is collected through the voluntary collaboration of police departments with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, so not the full picture. Also, police departments don’t always identify a shooting if an officer has been involved. Additionally, police-involved shootings that are under investigation are only counted once the investigation has concluded, so many recent incidents are not being counted.

Don’t other lives matter too?

The slogan “Black Lives Matter”, created as a riposte to the institutional racism that lingers on inside the American justice system, has met with its own controversy. Objectors have taken it to mean “black lives matter more”. The All Lives Matter campaign, for instance, is one among several groups that have sprung up to argue that every human life, not just those of black people, should be given equal consideration.

The police response

In the wake of the mass shooting of five police officers in Dallas in July, a new campaign has taken root. Blue Lives Matter, a national organization made up of police officers and their supporters, places the blame for what they see as a “war on cops” squarely at the feet of the BLM movement and the Obama administration.

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

But while the data tells a more positive story – that the average number of police officers intentionally killed each year has in fact fallen to its lowest level during Barack Obama's presidency – hate crime is still a daily reality in the US, and many feel that state-wide policies to curb it should be extended beyond the black community to include the police themselves. “Police officers are a minority group, too,” former police officer Randy Sutton, a spokesperson for the Blue Lives Matter campaign has been quoted as saying.

Back in Dallas, Chief of Police David Brown has been praised for his efforts to increase transparency and community-friendly policing. He has been credited with a reduction in police-related shootings and fewer complaints about the use of force by police officers.

What’s Campaign Zero?

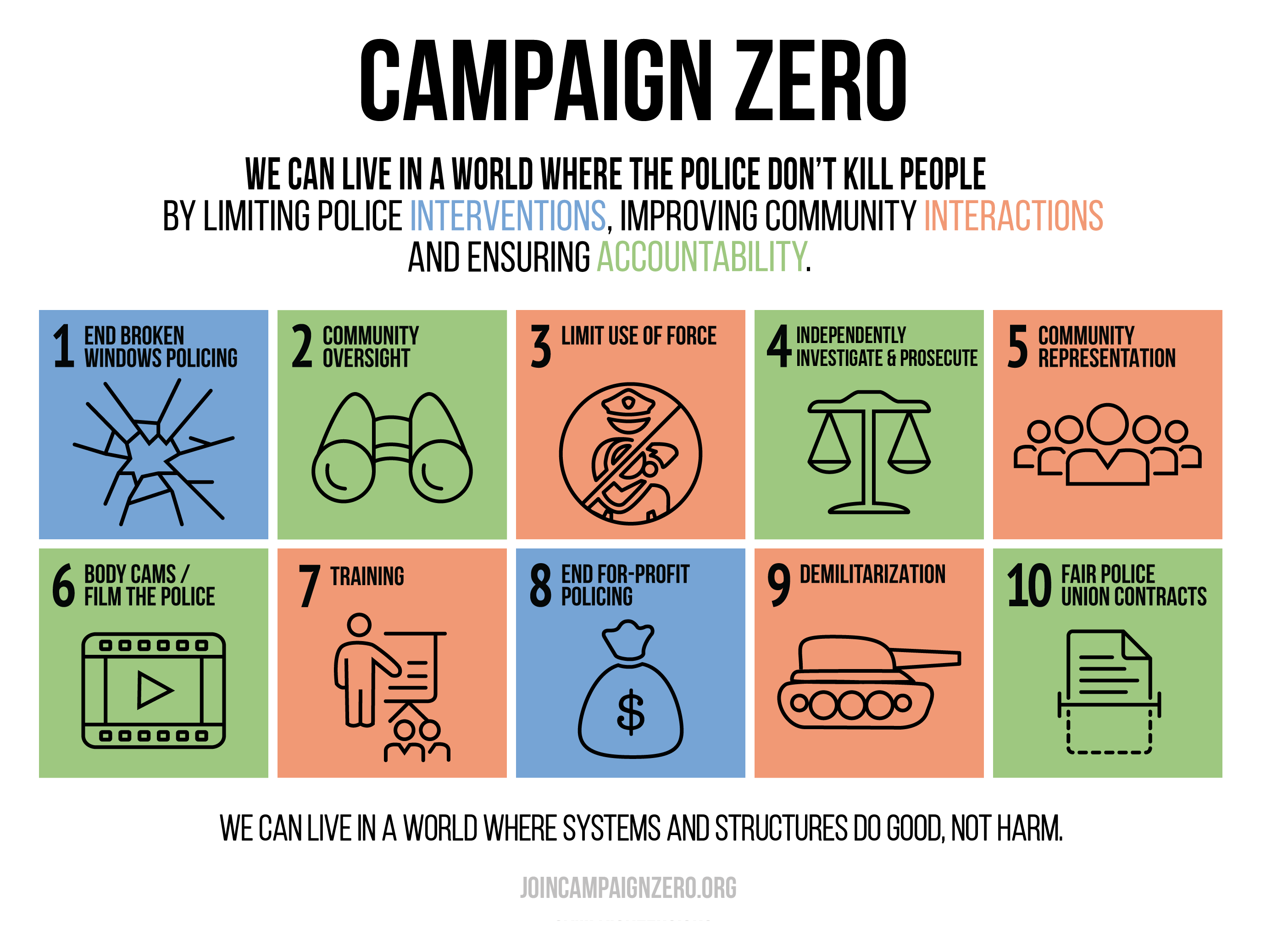

In 2015, the Black Lives Matter movement launched Campaign Zero, a group lobbying for changes to policies and laws on federal, state and local levels.

"We must end police violence so we can live and feel safe in this country," the group writes on the Vision Zero website. "We can live in a world where the police don't kill people – by limiting police interventions, improving community interactions and ensuring accountability."

What next for Black Lives Matter?

So far, the media has focused on the campaign’s events and protests on the street, but Black Lives Matter has also been involved in campaigning to change legislation.

As recently as August this year, the movement released more than 40 policy recommendations, including the demilitarization of law enforcement, reparation laws, the unionization of unregulated industries and the decriminalization of drugs.

Its efforts prior to that have had some success. One example is the creation of a “civilian oversight board” in St Louis City, which reviews and investigates citizens’ complaints and allegations of misconduct against the police.

Building on the legacy of the civil rights and LGBT movements, Black Lives Matter has created a new mechanism for confronting racial inequality. The movement also draws on feminist theories of intersectionality, which call for a unified response to issues of race, class, gender, sexuality and nationality.

Have you read?

Barack Obama: standout moments from his presidency

5 things to know about the US election

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Resilience, Peace and SecuritySee all

Benjamin Denis and Justine Roche

April 30, 2025

Dave Neiswander

April 28, 2025

Shoko Noda

April 23, 2025

Daniel Mahadzir and Natasha Tai

March 21, 2025

Robert Muggah

March 10, 2025