Endangered species wait an average of 12 years to get on the list

Scientists say the delays could lead to less global biodiversity.

Image: REUTERS/Santiago Ferrero

Stay up to date:

Future of the Environment

The wait time for getting on the endangered species list is on average about 12 years, six times longer than it should be, a new analysis shows. Scientists say the delays could lead to less global biodiversity.

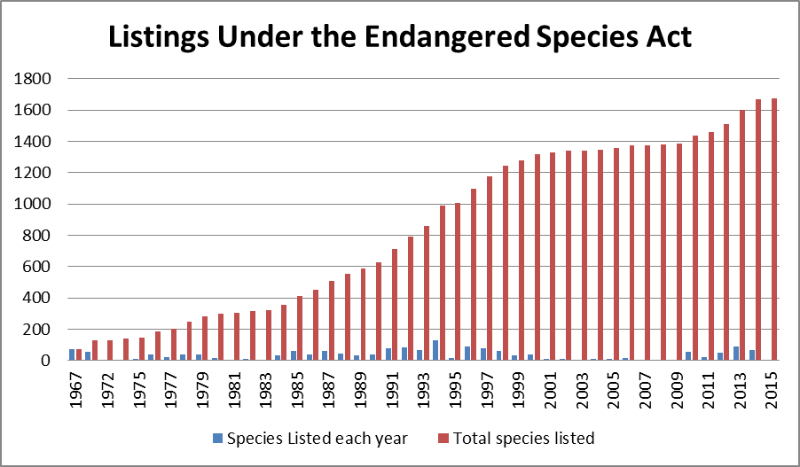

The US Congress enacted the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1973. To receive protection, a species must first be listed as endangered or threatened in a process that is administered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

“Without being on the list, we run the risk that these populations will go locally or globally extinct and there will be nothing to save.”

In 1982 Congress passed an amendment stating a two-year timeline for the process, which starts with submission of a petition and ends with a final rule in the Federal Register.

“While the law lays out a process time of two years for a species to be listed, what we found is that, in practice, it takes, on average, 12.1 years,” says Emily Puckett, who recently received her doctorate in the Division of Biological Sciences at the University of Missouri. “Some species moved through the process in 6 months but some species, including many flowering plants, took 38 years to be listed—almost the entire history of the ESA.”

Findings are based on an analysis of 1,338 species listed for protection under the ESA between January 1974 and October 2014. Researchers analyzed the amount of time it took each listed species to move through the listing process.

Bias for vertebrates?

Researchers also analyzed whether a species grouping influenced how quickly or slowly it moved through the process. They found that vertebrates, including reptiles, fish, birds, amphibians, and mammals had a significantly shorter wait time than did invertebrates and flowering plants.

According to the authors, the finding suggests a bias in the listing process that contradicts the policies of the ESA.

“While the [US Fish and Wildlife] Service can account for species groups in its prioritization system, it’s not supposed to be mammals versus insects versus ferns but, rather, how unique is this species within all of the ecological system,” Puckett says. “However, our findings suggest some bias that skews the process toward vertebrates.”

The delays in listing have real world consequences for endangered species. In the study, the authors cite previous studies that document species that went extinct due to a delay in the process.

Likewise, a species that gets listed quickly and has a conservation plan put in place to protect it may have a chance to even bounce back.

For example, the island night lizard was listed in 1.19 years, whereas the prairie fringed orchid took 14.7 years to be listed. The lizard has since recovered and been removed from endangered status; the orchid is still considered threatened.

“The whole point of putting species on the list is they already have been identified as threatened or endangered with extinction,” Puckett says. “Without being on the list, we run the risk that these populations will go locally or globally extinct and there will be nothing to save.”

The study appears in the journal Biological Conservation and was supported in part by a University of Missouri Life Sciences Fellowship and by the Institute for Bird Populations.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Nature and BiodiversitySee all

Tom Crowfoot

April 25, 2025

Sarah Franklin and Lindsey Prowse

April 22, 2025

Jeff Merritt

April 22, 2025

Elizabeth Mills

April 17, 2025

Tom Crowfoot

April 17, 2025