Why didn't the United States elect a female president?

Trumped ... was Hillary's fate sealed by misogyny?

Image: REUTERS/Adrees Latif

Stay up to date:

Agile Governance

It was supposed to be the day America would catch up with history and the rest of the world. Finally, the US would elect its first woman president.

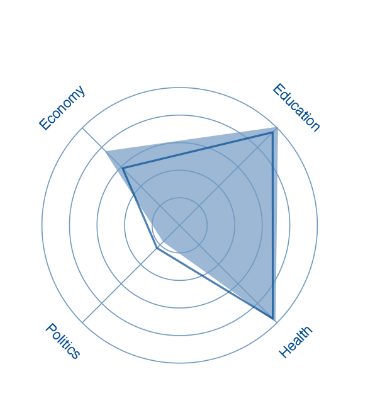

It turns out that the catch-up will be delayed. When it comes to political empowerment, the United States is ranked 73rd out of 143 countries, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2016.

The US is slowly falling down the list – not because its record on electing women is getting worse, but because other countries are getting substantially better. Today there are 60 members of the Council of Women World Leaders, all of them current or former freely elected heads of state or government as president, prime minister or chancellor. On the list of countries that have had such a leader in the past 50 years, the US is dead last.

The obvious question is, why? Why can’t the world’s most powerful nation elect a women president?

In trying to parse how much of this failure is the unpredictability of politics’ rough-and-tumble process and how much is sexism, I separate the causes into two categories: the seed and the soil. The seed is the individual candidate. The soil is the ground in which that candidate has to try to prosper: the institutional structures and processes that either facilitate change or throw up barriers.

Winner takes all

The United States and its winner-take-all system is tough soil for new growth to take root in. The electoral college, not the popular vote, determines who gets elected, giving more weight to outliers in middling states like Michigan or Ohio. In this system, third-party candidates can act as spoilers, preventing major party candidates from gaining a clear advantage in some states.

The hurdle for women is lower in countries in a parliamentary system, where the multiple parties can agree to back one another’s leaders in coalitions. Parliamentary elections also put more parties in play. The more parties in play, the more opposition leaders there are. And since women often become opposition leader before they become prime minister, there are more opportunities for women to take the top job. Women also often find an entry point to the presidency in countries where the prime minister is the executive and the president wields more symbolic “soft power”.

More than 100 countries, furthermore, promote women’s chances to lead with some sort of quota system, requiring a certain minimum number of seats in parliament to be filled by women. Women are given the chance to hone their political skills as a member of parliament or deputy, establishing a well-stocked pipeline of experienced women legislators prepared to run for the high office.

In the US, where no such quotas exist, the percentage of the House and Senate seats held by women seems to plateau at about 20%, never attaining what many regard as a critical mass of 35%. Affirmative mechanisms are highly unpopular and unlikely to be enacted.

Quotas don’t advance unqualified women but remove in-group favouritism and closed social networks, so qualified women can advance.

Question of stamina

Fighting to lodge in this forbidding soil, the seed has its own disadvantages. Women simply do not fit the archetype of a leader in a country that stakes its superpower status on its military might. Men are presumed to be strong until they show otherwise. Women must prove they have strength, which is what made Donald Trump’s attack on Hillary Clinton’s “stamina” so effective. Using this code word, he played on Americans’ unconscious fear that Clinton was not strong enough to be commander-in-chief.

Nearly all of the female leaders in the Council of Women World Leaders have experienced scrutiny of their hair, dress, voice and style that men get much more rarely. In the seemingly endless US election campaign, the objectification of Hillary Clinton went beyond hyper-scrutiny to misogynistic name-calling, with anti-Clinton T-shirts and signs reading “Trump the bitch”.

Trump was accused of this kind of misogyny, and his rise gave voice to an unsettling loss of centrality among some supporters, encouraging them to abandon political correctness, as they saw it, and vocalize their unease at the advancement of women (and other historically underrepresented groups).

Of course, women are judged for themselves as much as men are: on their experience and their message, and their likeability. Clinton, with her baggage of investigations dating back to her husband’s administration and her more recent history of email troubles, was widely seen as an imperfect messenger and therefore not deserving of the presidency. In her book Lean In, Google CEO Sheryl Sandberg says that women must be liked, and Clinton, polls showed, was not liked. But neither was Trump – his unfavourable rating was worse than his opponent’s – yet he is president-elect.

This anomaly points to a tolerance gap in American politics when it comes to mistakes or misjudgements. In the scrupulous fact-checking that the press conducted, prompted by Trump’s constant straying from the truth, Clinton was cited for roughly a fifth the number of “less than true statements” as Trump. Nonetheless he successfully branded her a “liar”. A simple litmus test: put one of Trump’s false statements in Clinton’s mouth (“Crime is rising”; “We’re the highest taxed country in the world”) then ask how the voters would react.

This was a peculiar and particularly difficult election for our female presidential candidate, but only in degree. These same individual and institutional difficulties challenge women at some level in every US election. The country now ranks 93rd in representation in the two houses of Congress, according to the Interparliamentary Union.

According to Saadia Zahidi, an economist at the World Economic Forum who authors the Gender Gap Report, 47% of all countries have had at least one female head of state, ever. At the current rate, Zahidi has projected, it will take more than 100 years for the world to get to gender parity, where half of all heads of states are women at any given time. Will the United States get there by then?

The silver lining is that women around the world are making substantial progress in reaching highest-level offices. That progress will continue and be sustainable as more women see that it is possible and desirable.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Geo-Economics and PoliticsSee all

Richard Samans

April 17, 2025

Sean Doherty

April 16, 2025

Spencer Feingold

April 8, 2025

Neville Lai Yunshek

March 25, 2025

Kim Piaget and Yanjun Guo

March 17, 2025

Robert Muggah

March 10, 2025