In Latin America, companies still can’t find the skilled workers they need

50% of Latin American companies cannot find staff with the skills they need Image: REUTERS/Jorge Adorno

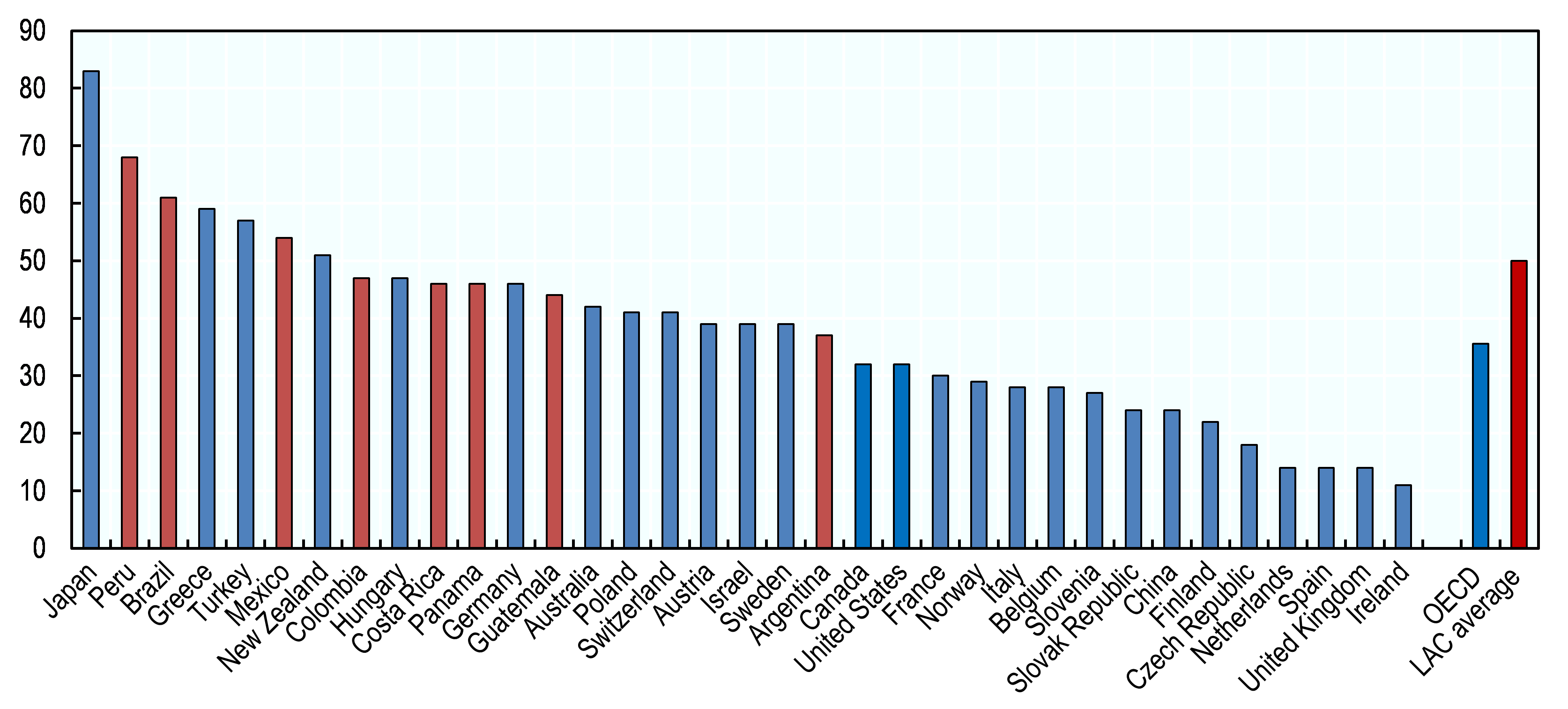

Latin America faces an acute skills shortage. Around 50% of formal Latin American firms cannot find candidates with the skills they need, compared to 36% of firms in OECD countries, according to Manpower. This is a particularly pressing issue in Peru, Brazil and Mexico.

A lesser known fact is that the sectors with the biggest skills gap in Latin America are the ones that are more beneficial for development and industrial upgrading, such as motor vehicle and advanced machinery.

At the same time that Latin America has the world’s highest skills shortage in the formal economy, two out of every five young people are neither studying nor working, and 55% of workers in the region work in the informal economy. Workers clearly do not have the skills that companies need, and companies are having a very hard time finding the talent they require to grow their businesses.

The good news is that most governments are aware of this priority and understand that skills have become the global currency of 21st century economies. The lack of an adequate pool of skilled workers prevents the emergence of new growth engines. Also, the increased complexity of skills required to succeed in today’s global economy, and the rapid speed at which skill needs change, impact the ability of formal education systems to provide timely solutions. Therefore, investing in the right skills is one of the key ingredients for an inclusive growth agenda, one that boosts productivity and empowers people to integrate fully into society.

Solving this skills problem requires bold policy reform. Expanding education coverage is not enough; instead, policy-makers must also focus on raising the quality of education.

Also, much less emphasised, but in our opinion, equally important, is the need for upgrading the relevance of curricula and sharing information about which skills are in high demand.

In addition, reforms should target not only the skills of the school-age population, but also the skills of the labour force. It is the skills of those who are in the labour force today that will power economies in the next 30 years. This implies investing in more effective and relevant training systems and adapting formal education to the needs of people who work. This includes, for example, making education more modular or expanding the reach of work-based learning so people can attain certifications while working.

To achieve these goals, governments need to invest in capacities to anticipate skill needs and detect skills mismatches. They also need to involve employers in skill development systems. These strategies will help make it possible for education, particularly technical education, and training systems to become more attuned to employers’ skill needs. In addition, rigorous evaluation mechanisms should be implemented to identify what works better for firms as well as workers, particularly in terms of earnings quality and labour market security.

Examples of such brave moves can already be seen in the region. Several countries – such as Chile and Brazil – are beginning to invest in labour information systems to detect and anticipate skill shortages. Some industries are creating sector skills councils to identify the behaviours and competences that are required for workers across different roles and across different levels of complexity. This is taking place in Chile, for example, in the skills mining council and in the wine cluster.

A number of countries are also beginning to experiment with apprenticeships and dual education models, with the strong support of employers, providing people with both a job and a pathway to learning and certification. Examples include the dual education model in Mexico, the forthcoming apprenticeship programme in the Bahamas and the initiatives being developed by the Global Apprenticeship Network.

The Latin America and Caribbean region cannot afford to be left behind. Now, more than ever, better and more relevant skills are needed. To achieve that, we need joint efforts from governments, companies and citizens.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Latin America

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Education and SkillsSee all

Jumoke Oduwole and Abir Ibrahim

November 11, 2025