How Saudi Arabia can become a post-oil economy

Saudi Arabia is aiming to install 9.5 gigawatts of solar capacity in the next six years

Image: REUTERS/Fahad Shadeed

Stay up to date:

Middle East and North Africa

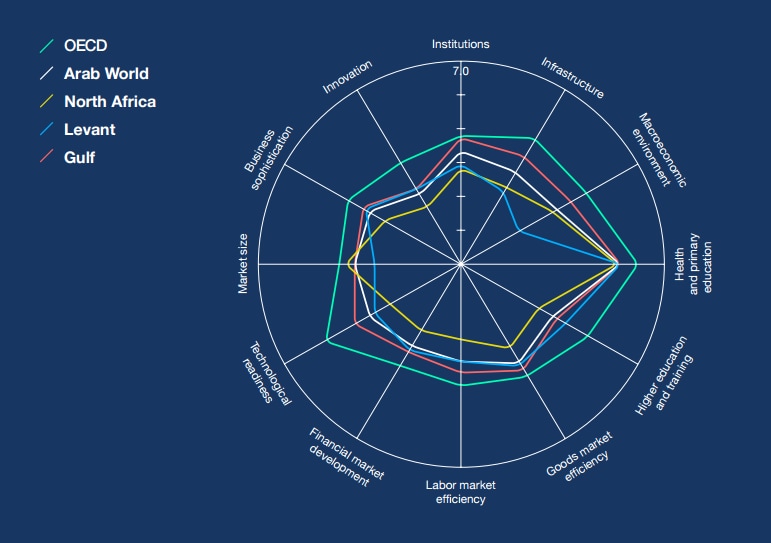

Saudi Arabia has achieved much of its past economic success on the back of endowments of natural resources, particularly oil and gas. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 reflects a clear recognition that this foundation of the economy is too narrow, particularly as the population grows and domestic energy demand increases. It lays out a clear mission to transform the economy to make it more diverse, innovative and competitive - allowing the necessary policy actions to develop.

Energy has underpinned economic and social development of the Kingdom for several decades. Indeed, strategic decisions were made to build wealth on the back of the Kingdom’s large resource endowment and to distribute the benefits by providing low-cost energy to both individuals and industry. Such welfare distribution is normal – most resource-rich countries follow this approach, both to stimulate growth and to help those that need it through subsidies.

Global energy markets are evolving rapidly in ways that have huge implications for the Kingdom. A transition to a lower carbon economy among many of Saudi Arabia’s key customers for its crude oil and products is being driven by international climate commitments under the Paris accord. Electricity is currently the main focus of this transition – more a threat to coal and natural gas than to oil in the short term. But the link to oil will likely come from the electrification of mobility, particularly as automated, shared mobility on demand moves from disrupting taxis to the mainstream of transport services consumption.

Shifting to solar

For as long as Saudi Arabia’s abundant natural resources delivered high revenues, there was little incentive to think about using its solar resources efficiently in the domestic context. But now, Saudi Arabia is aiming to install 9.5 gigawatts (GW) in the next six years. While small in relation to the 10GW of solar China aims to install annually, the Kingdom is at the start of the process and may well adjust targets upward as costs decline and local skills and learning are built up. A recent investment in Uber positions Saudi Arabia in the reshaping of mobility, both in the Kingdom and around the world.

Continuing the extensive support to traditional industries has led to market distortions. Saudi policymakers recognize the need to transform the economy – starting with how energy is used. It is clear that some of the supported industries can be self-sustaining, and that some of the incentives can be reallocated along the value chain; for example into manufacturing of finished goods rather than intermediate bulk products.

While economic diversification is an imperative, it will not be at the expense of the energy-intensive industries that have been staples of the economy. There is scope to run these businesses more efficiently and avoid incentives that distort markets. For example, in some industrial sectors that rely on carbon or on carbon-based power, the energy component of goods manufactured is as high as 70% to 80% of production, whereas similar goods produced in other countries have an energy component as low as 15% to 20%. Saudi Arabia is better prepared now to take measures to reform these industries while, at the same time, taking care to avoid risks of a “shock” to the system.

This culture of inefficiency is starting to change. New regulations and initial price reforms are beginning to replace the long-standing practice of keeping energy prices low (reflecting the low cost of domestic production) as a means of distributing natural resource wealth. There is a determination to eliminate inefficiency and waste. While more efficient technologies and practices are available (and indeed have become the norm in other contexts), Saudi Arabia faces an overarching challenge of changing social norms, which will require both policy action and public awareness.

Changing bad habits

The challenge now to the energy sector is how to encourage customers to change their behaviors and adopt efficient practices. One approach is to lead by example: Saudi Electricity Company plans to invest in the transmission network to reduce energy losses and also to optimize the mix of fuels and technologies in its generation fleet to maximize efficiency. Privatization will provide stronger incentives in this regard.

There is a strong focus on the residential sector, which accounts for 60% of electricity consumption. The building code is becoming more stringent and resources are being put into implementation and enforcement. The Saudi Energy Efficiency Center has launched several initiatives for efficient appliances. Additionally, more than 40 organizations are investing in public-awareness campaigns (including through social media) so that people become more “energy-literate”. There is also a role for energy price reform, which is necessary regardless of other specific programs, in stimulating change.

The younger generation of Saudis is already behaving in ways that have the collateral result of different energy consumption patterns. They are marrying later and having fewer children, leading to lower consumption per household. In fact, they are generally more environmentally and ecologically conscious and are showing interest in climate change. This shifting mindset creates a window of opportunity to incentivize an end to old, wasteful behavior and encourage commitment to energy efficiency.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Energy TransitionSee all

Andrea Willige

May 13, 2025

Roberto Bocca

May 9, 2025

Kesang Tashi Ukyab and Leo Simonovich

May 9, 2025

Nii Ahele Nunoo

May 6, 2025

Denise Rotondo and Chris Leong

May 5, 2025

Don McLean

May 1, 2025