Five facts on what trade and technology really mean for jobs

'Trade has helped to spur a transition from middle-class manufacturing jobs to services jobs'

Image: REUTERS/Darren Whiteside

Stay up to date:

Trade and Investment

Technology and trade have driven the global economy through a period of extraordinary growth and dynamism over the past quarter of a century but at a cost of important changes and disruptions in the job markets.

The 2017 edition of the World Trade Organization's World Trade Report (WTR), examines how technology and trade affect labour markets.

The WTR notes that while the scale and pace of recent global economic change is unprecedented, the process is not new.

Ultimately, continued economic progress hinges on the ability of economies to adjust to changes and promote greater inclusiveness.

While today’s labour market problems are largely traceable to domestic policy shortcomings, a failure to find answers could have global ramifications.

The WTO provides a platform, along with other relevant international organizations, where governments can discuss and negotiate cooperative solutions to the opportunities, as well as the challenges, of ongoing global economic change

Below are five important findings of this year's report.

1. Labour market evolution remains highly diverse across countries with some general trends.

Labour market evolution has been marked by a higher share of highly educated workers, increasing participation of women, declining participation of men, and an increasing number of non-traditional arrangements, such as work based on temporary contracts, part-time work and self-employment.

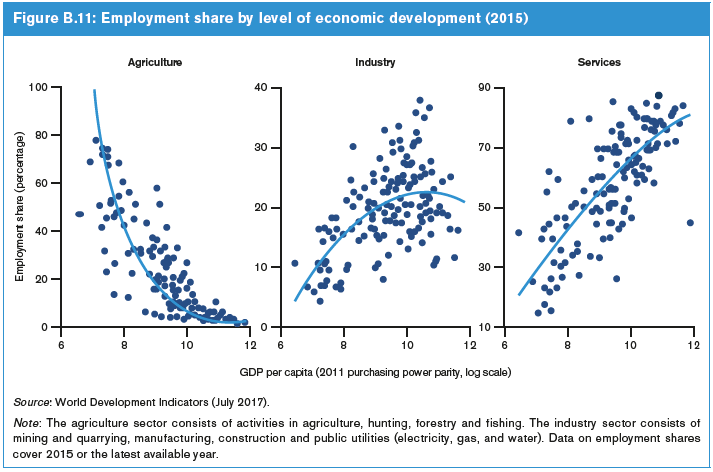

The share of workers in services continues to grow in both developed and developing economies, while the share of workers in agriculture and manufacturing is declining or stagnating in developed countries and increasingly in developing countries.

At the same time, the share of high- and low-skilled occupations in total employment have increased and the share of middle-skill occupations has declined in developed economies and a number of developing countries.

Overall, labour market evolution is different across countries, suggesting that country-specific factors play a vital role. Factors, such as macroeconomic conditions, labour market institutions and mobility frictions or obstacles, vary widely across countries, but play an important role.

2. Trade tends to increase employment and wages, but not all workers may benefit, as regional and individual differences determine how gains are shared.

Although trade opening tends to increase overall employment and wages, certain regions, sectors, and individuals may be left worse off in the absence of adequate policy responses.

Empirical evidence suggests that trade can explain up to 20-25% of the recent decline in US manufacturing jobs. The remaining 75-80% is explained by other factors, such as technological change.

Just like technological change, trade increases the relative demand for high-skilled workers, especially in non-routine occupations, as well as the nominal wages of high-skilled workers relative to low-skilled workers in both developed and developing countries.

Trade increases the purchasing power of poor, low-skilled workers by enabling them to purchase a more affordable and wider variety of imported products therefore increasing their wages in real terms.

Trade, along with other factors, has also fostered a transition from middle-class manufacturing jobs to services jobs.

3. Globally, millions of individuals work in trade-related activities.

Jobs are created not only to fulfil a country's domestic demand, but also to produce goods and services that are directly exported to other countries, or used to produce goods and services that will be exported by other firms.

The share of export-related jobs in domestic employment can reach up to 30 per cent of total employment in some countries.

Import-related activities support also job creation by improving firms' competitiveness and creating downstream jobs.

In addition, both exporting and importing firms pay higher wages than firms focusing exclusively on the domestic market.

4. Labour market changes and the composition of employment are driven by technological progress.

Technology makes some products or production processes obsolete, and creates new products or expands demand for innovative products, which leads to the reallocation of labour across and within sectors and firms with important repercussions for workers.

Technological progress can assist workers, through labour-augmenting technology, or replace them, via automation. In both cases, the overall effects on the market’s demand for labour are ambiguous.

Current technological progress has led to a higher relative demand for skilled workers and a lower relative demand for workers performing routine activities.

Computers in the workplace have been the central force driving changes in the wages of skilled workers relative to the wages of unskilled workers.

The upcoming wave of technological advances, such as artificial intelligence and robotics will likely continue being disruptive, making some skills obsolete, while enhancing others and creating new ones.

5. Domestic policies, macroeconomic conditions and barriers to worker mobility play an important role in determining how the benefits associated with technological change and trade are shared.

The ability of workers to adjust and move from lower- to higher-productivity jobs and from declining sectors to rising ones is one of the mechanisms through which technological progress and trade contribute to growth, development and rising living standards.

Through a mix of adjustment, competitiveness and compensation policies, governments can help workers to manage the cost of adjusting to technological change and trade, while making sure that the economy captures as much as possible the benefits from these changes.

The balance needed between adjustment, competitiveness and compensation measures varies according to the political, social and economic circumstances of the country concerned.

In developing countries the larger share of workers in the informal, agricultural and state-owned enterprise sectors needs to be taken into account.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Trade and InvestmentSee all

Philippe Isler and Mariam Soumaré

May 2, 2025

William Dixon

April 28, 2025

Alem Tedeneke

April 25, 2025

Jimena Sotelo

April 25, 2025

Don Rodney Junio

April 24, 2025

Manfred Elsig and Rodrigo Polanco Lazo

April 23, 2025