Why we need to calculate the economic costs of sexual harassment

Studies of the financial costs of sexual harassment are few and far between. This needs to change.

Image: REUTERS/Carlos Garcia Rawlins

Stay up to date:

Economic Progress

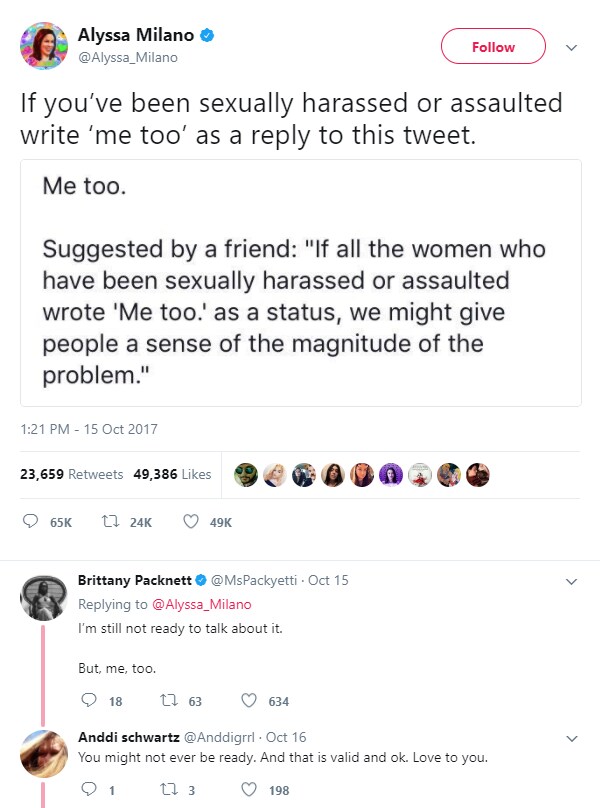

The allegations made by Hollywood celebrities against movie producer Harvey Weinstein have triggered a broader conversation about sexual harassment in the workplace. Using #MeToo, #balancetonporc, #yotambien and more, women (and some men) around the world have taken to social media to share their experiences of sexual harassment and assault.

An underreported problem

The amount of workplace harassment – including sexual harassment – is well documented. A 2016 study by the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission revealed it had received 90,000 complaints in 2015 alleging some form of harassment, and said that the problem is underreported.

And in the UK a survey last year of 1,533 women found 52% had experienced workplace sexual harassment.

What is surprising is that there is little up-to-date research into the economic impact of sexual harassment on victims in terms of missed career opportunities, and on the companies and organizations that failed to prevent it happening in the first place.

A much-quoted US survey, answered by personnel and human resources directors and equal-opportunity offices representing 3.3 million employees at 160 corporations, came to the conclusion that a typical Fortune 500 company with 23,750 employees lost $6.7 million a year because of absenteeism, low productivity and staff turnover as a result of sexual harassment.

However, this study dates from 1988 and it is hard to find more contemporary evidence-based research into the financial damage sexual harassment causes.

Despite the financial and reputational cost to companies of high-profile payouts – such as the $45 million that 21st Century Fox paid in the first quarter of 2017 to settle allegations of sexual harassment – executives seem unaware of the scale of the problem, or choose to ignore it.

Fighting for equality

There is plenty of evidence, however, that shows women do not have equal status in many workplaces, and are not being promoted to senior roles, which can make tackling sexual harassment more difficult. Studies also consistently demonstrate that women are underrepresented in certain industries, including technology.

Tales of mistreatment of women in Silicon Valley abound. Travis Kalanick, Uber’s former chief executive, was forced out of that role earlier this year following an investigation into a corporate culture that had ignored complaints about sexual discrimination and harassment, though Kalanick still remains on the board.

And a male Google engineer sparked a storm earlier this year by suggesting in a blog that women may be unsuited to tech roles because of “genetic differences”.

Evidence from around the world – from the debate about gender pay discrimination at the BBC, to studies that show 59 countries have no laws against workplace sexual harassment – tends to support the theory that women are still being treated as second-class citizens across countries and industries.

This is despite the fact that more women are entering labour markets. For example, the percentage of economically active women in the United Arab Emirates increased from 9.6% in 1990 to 12.5% in 2016, and in the UK from 43.3% to 46.4% over the same period, the World Bank estimates.

Without support from corporate leaders and policy makers, it is hard to see how things will change. As the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission said in 2016, leadership on this issue has to come from the top, although we can all make a difference. It added: “Harassment in the workplace will not stop on its own – it’s on all of us to be part of the fight to stop workplace harassment.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Danny Rimer

July 14, 2025

Silja Baller and Fernando Alonso Perez-Chao

July 11, 2025

Yusuf Maitama Tuggar

July 10, 2025

Resilience roundtable: How emerging markets can thrive amid geopolitical and geoeconomic uncertainty

Børge Brende, Bob Sternfels, Mohammed Al-Jadaan and Odile Françoise Renaud-Basso

July 9, 2025

Gayle Markovitz and Beatrice Di Caro

July 9, 2025