New Zealand is using gene editing to control wildlife

New Zealand may use gene drives to eliminate pests, but this could drastically change the ecosystem.

Image: REUTERS/Tim Chong

Stay up to date:

Future of the Environment

New Zealand’s Plan for Gene Drives

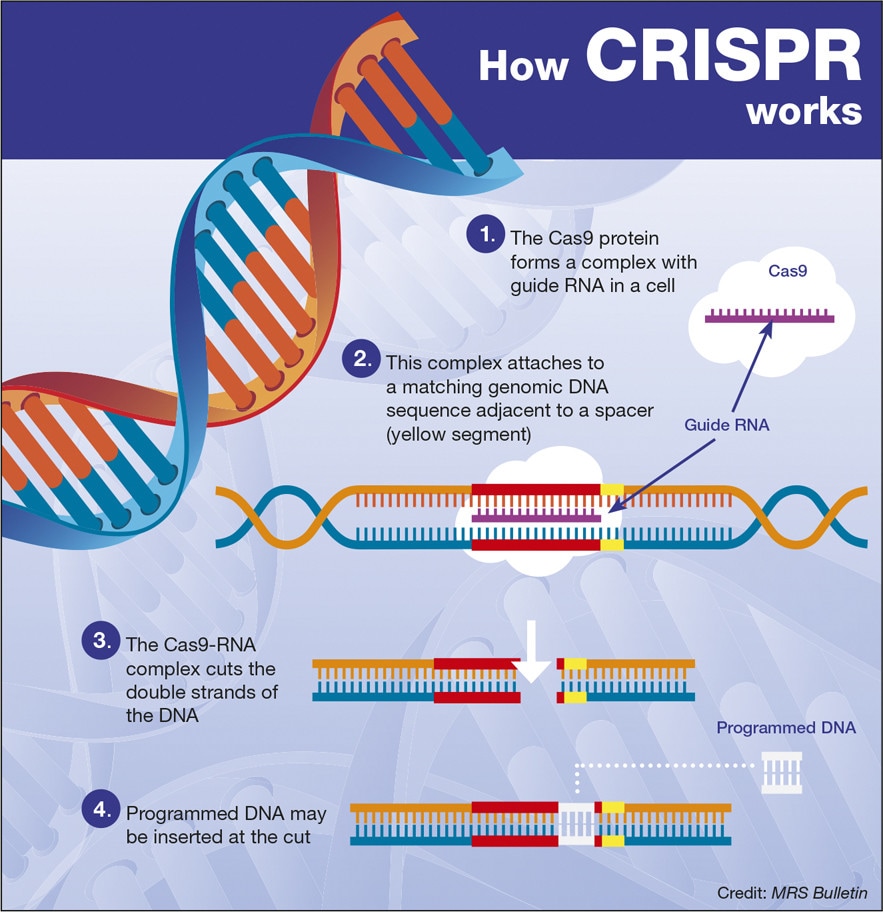

Experts are considering using gene editing technology as a tool for addressing some of the great biological challenges facing the world today: everything from controlling or limiting the growth of vector-borne diseases to promoting conservation. Scientists in New Zealand are specifically interested in the potential of engineering gene drives, which are made possible by the gene editing tool CRISPR.

A gene drive system uses gene editing to promote the inheritance of a particular genetic variant, thereby increasing its frequency in an organism’s population. New Zealand is considering gene drives as a tool to reduce the population of pests like rats, mice, stoats, and possums — if not eliminating them altogether. The move has generated global interest, sparking a debate about the use of gene drives.

In a study published in the journal PLOS Biology, Neil Gemmell from the University of Otago, New Zealand, and Kevin Esvelt from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) studied the possible consequences of accidentally spreading existing self-propagating gene drive systems.

“I think it is important to point out that our piece is aimed at informing and provoking discussion about gene drives in a global context and that we are not against gene drive technology per se, or indeed opposed to the idea of exploring this technology as a component of the technical solutions that will enable New Zealand’s predator-free goal,” Gemmell told Futurism.

“The bottom line is that making a standard, self-propagating CRISPR-based gene drive system is likely equivalent to creating a new, highly invasive species — both will likely spread to any ecosystem in which they are viable, possibly causing ecological change,” Esvelt, who was among those who first described how gene drive could be accomplished using CRISPR, explained in a press release.

Rapidly Emerging Solutions

Engineering gene drive systems have the potential to be highly effective, but experts still have certain misgivings regarding their use. “I see gene drives as an important future solution to a variety of problems in the conservation domain, but they need to be controllable in some context if we are to seriously consider deployment in an environmental context,” Gemmell explained.

As Anthony James, the Donald Bren Professor of microbiology and biochemistry at the University of California, Irvine’s School of Biological Sciences, told Futurism, the true potential of gene drives can only be realized “following comprehensive laboratory testing.”

“We are living already worse-case scenarios (human and animal disease and death, extinction of valued island species) and gene drive technologies offer potential solutions,” James added. “They may not be appropriate in every case but should be explored for those in which they could have a benefit that far outweighs the costs.” Identifying and addressing such circumstances, he said, will be the most prudent task.

The potential of gene drives is clear, but how soon could these systems be safely deployed? Gemmel suggests, based on experiments with fruit flies, that we could expect to see them in 3-5 years. However, he also added a caveat: he’s not sure if we’ll “have the social, ethical and legal frameworks for such deployment in place” within that timeframe.

Indeed, Gemmell and Esvelt warned about the consequences of a gene drive system affecting an entire species beyond what was intended. “[T]he prospect of nations suing each other to compensate for the ecological damage and perhaps social and cultural damage and it could be a real mess,” Gemmell explained, saying this could push back gene drive research due to lack of confidence in the technology.

“With open dialogue and research, I am hopeful that new solutions will rapidly emerge so that we will have gene drive systems that can be controlled in a variety of ways e.g. such as the finite lifespan predicted via [Esvelt’s] daisy chain gene drive,” Gemmell said. “The technology is, after all, only a few years old and with the speed of development we are witnessing, new more readily controllable tools are likely not far away.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Nature and BiodiversitySee all

David Elliott

June 19, 2025

Jean-Claude Burgelman and Lily Linke

June 18, 2025

Georgina Mondino and Maximiliano Frey

June 18, 2025

Forum Stories

June 17, 2025

Lindsay Hooper

June 16, 2025

Swapan Mehra and Akim Daouda

June 16, 2025