What impact will automation have on our future society? Here are four possible scenarios

While nobody really knows how our lives will be changed by the rise of robotics, here are four possible scenarios.

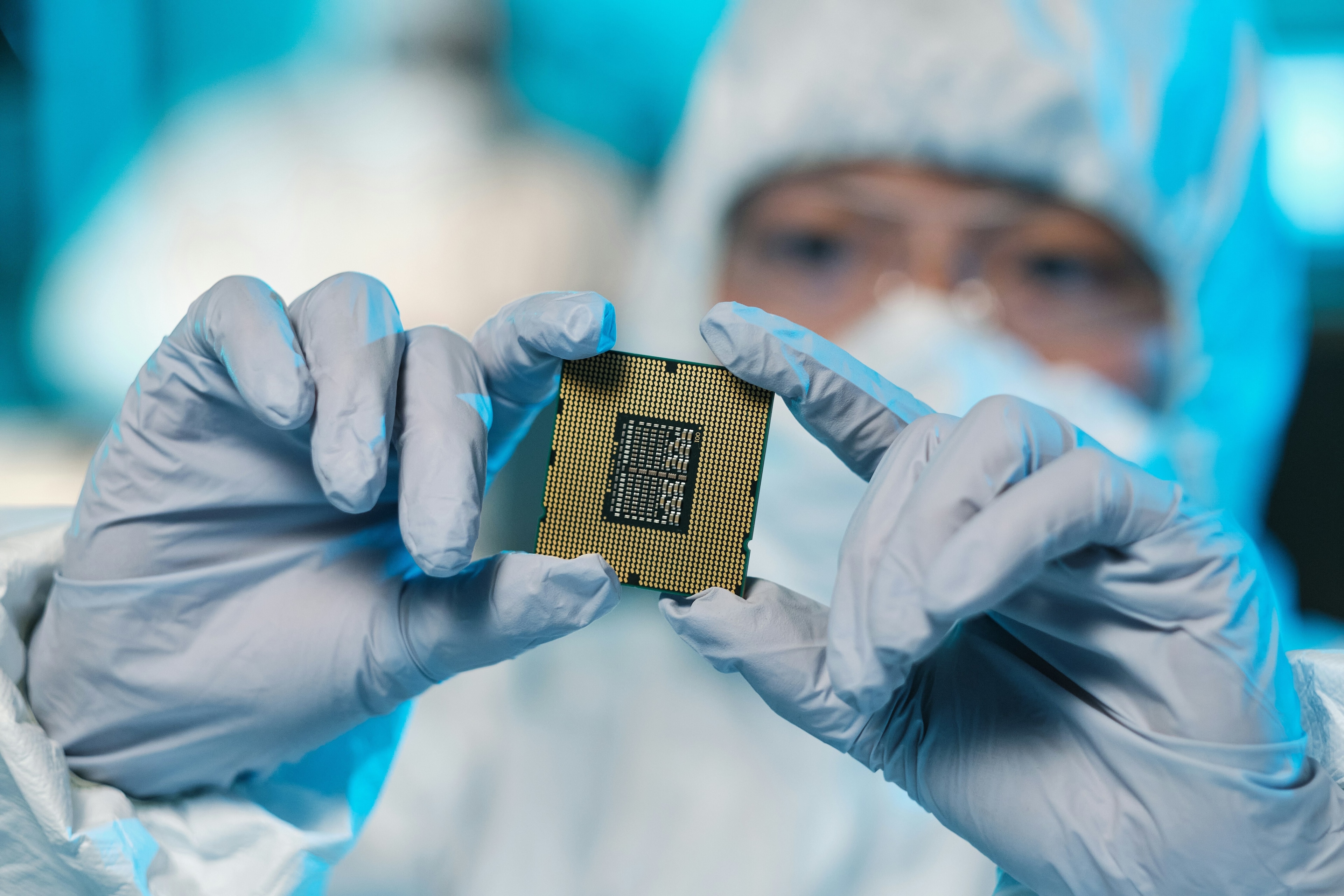

Image: REUTERS/Michaela Rehle

Stay up to date:

Future of Consumption

We often hear from technology entrepreneurs, futurists, and some media outlets, that automation will lead to a bright future. At the same time, there is a significant number of intellectuals, politicians and journalists depicting doomsday scenarios for our automated future.

Much of the current debate is shaped by these extreme hypotheses. You are either in favour of automation and everything that comes with it, or against it. This is astonishing, since similar discussions were already led in the pre-internet age about similar topics. We currently repeat them without providing new solutions.

It is worth looking at four scenarios for our future with differing automation intensities, to stimulate a broader discussion that does not just address extreme opinions, but also the spectrum in between. In this context, artificial intelligence research is considered to be the main enabler for future automation.

Scenario 1: Balanced automation and technological boundaries

Artificial intelligence research was full of promises and controversial discussions several decades ago, when scientists focussed on expert systems in the 1980s. In 2018, we still develop narrow artificial intelligence, but once again there are visions of an omni-tasking superintelligence. Yet, deep learning, the current poster child of artificial intelligence research, is unlikely to fulfil this utopian vision.

Looking back at the history of artificial intelligence, it is plausible that we will witness similar setbacks in research interest or a temporary plateau in technological advancement, which might be caused by bottlenecks in computing power, quality of training data, or an inability to understand the outputs. In certain domains we might be able to develop systems to fully automate a cluster of tasks from end-to-end, like driving or financial modelling, but others might remain obscure for artificially intelligent systems.

It is important to bear in mind, that most jobs consist of multiple sub-sets of tasks from different domains, requiring a multitude of skills. A job could require communication, numerical calculations, logical reasoning, data aggregation, analytics, creativity, social skills, dexterity, processing of auditive, olfactory or visual stimuli and much more.

So, even if it would be possible to automate certain sub-tasks of one macro-task using different systems, it might not be feasible to combine them together in order to fully automate the macro-task. Furthermore, automation comes at a cost, which could make it financially unattractive to automate certain jobs, even if it might be imaginable from a scientific point of view. Adding to this, we must acknowledge that automation is dependent on data, which is not always available in the required quantity or quality.

Due to these issues, human labour would remain superior and cheaper in a majority of professions. As a result, humanity would be able to automate certain tasks, decide not to automate others, and, in certain cases, simply not be able to automate them at all. Bearing this in mind, balanced automation will progress slower and will not be as disruptive as currently predicted.

Scenario 2: Irrational automation behaviour and external limitations

Just because we have developed something, we do not have to use it. We, as a society, might be able to fully automate our lives in the future, either by machine learning, bio-engineering or some other technology, overcoming the technological boundaries envisaged in the previous scenario. But the truth is, there is no-one forcing us to make use of our knowledge on a grand scale.

Most discussions about automation build on the assumption that we will use the technology available. Yet humans are irrational decision makers. Hence, we might selectively automate tasks that we do not like and keep the rest, even if the output would be of a lower quality. Humans could simply resist change or start to value human work more than its automated counterpart. Our society could also shift away from its technological innovation trajectory, because of potential resource scarcity, pollution, conflicts or other external influences.

In this scenario, humans could overcome the technological limitations from scenario one. Theoretically we would be able to fully automate most tasks, yet cultural change would not be as fast as technological transformation. External inhibitors could force us to a lower automation intensity. Hence, we would be required to diligently select where we want to continue to use automation technology and merge it with previously applied technology as well as traditional knowledge.

Scenario 3: Ubiquitous and planned automation

We might achieve what previously seemed impossible: the creation of a general purpose artificial intelligence. Quantum computing could finally arrive on the mass market. Data collection through sensor-enhanced infrastructure, and legal frameworks allowing monitoring online as well as offline behaviour, might provide a continuous stream of highly granular real-time training data.

Due to the combination of artificial intelligence, biology, healthcare and other disciplines, science might gain proficient understanding of complex systems such as human health, behaviour and our environment. This knowledge could be used not just to automate human labour as much as possible, but also to develop an alternative political, social and economic system, which is compatible with the future status quo.

While profiting in many ways from automation and new technologies, humanity would be willing to accept the intrinsic risk posed by a general purpose artificial intelligence. It would become accepted that human cognition is not able to understand the output produced by every intelligent system.

In order to fill the void of unemployment, humans would focus on inter-human connections and create an experience-based economy, where cooking, nursing care, handicraft and other ‘human experiences’ might be valued the most. Gaps between those resistant to change and those more technologically-minded could be met with training programmes and monetary support, financed by an automation tax.

Scenario 4: Rapid full automation

In case of rapid full automation, we would have to quickly rethink human labour, redefine our entire value system and redesign theories we currently stick to. Capitalism, for example, is currently seen by many as a driver for innovation, but its underlying theory might face some issues in this future scenario. Capitalism’s hypothesis is that economic growth and gains in productivity lead to more consumption and ultimately translate into higher wages, thus positively impacting the overall economic well-being of society.

In the case of full-automation, corporate monopolies that will have created these automated systems or amassed the most data, would eventually aggregate power and money, while breaking the logical implication from productivity gains to higher wages, because there would not be enough human jobs. In consequence the driver of growth, consumption, would be inhibited.

Whether the egalitarian idea of a universal basic income could be a feasible solution remains to be seen, as humans have always strived to distinguish themselves from their peers, in the pursuit of social status. Hence, social inequality might become more extreme, with an elite group of people that either have professions that could not be automated, or who directly profit from automation.

Scenario four differs from scenario three mainly regarding the speed of automation and its unplanned approach. While scenario three has already created a meaningful alternative for our current system, scenario four focuses on financial gains of a small minority, leading to more inequality.

What’s next?

None of these scenarios are carved in stone. On the one hand, there is no absolute certainty of extreme disruption, leading to a predicted potential automation of 50% of the workforce or more. It might just remain a hypothesis. On the other hand, we should not relax and assume that humankind will simply deal with any upcoming change, because we have done so in our past.

Likewise, we should not continue to trump each other with even more abysmal doomsday predictions or even shiner promises for a utopian future. Though proceeding with prudence might not be the most exciting thing to do, we should try it because this will ensure we are better prepared for the future.

Hence, we should start a democratic, pan-national public discourse in order to hear everyone’s needs, fears, ideas and hopes. Furthermore, governments should subsidize more independent multi-disciplinary research evaluating ethical, social, legal, environmental and technological implications of future automation, while developing ideas for solving issues that might arise. Ultimately, we should accept that our plans might be flawed, since the complexity of future change is beyond current predictability.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Emerging TechnologiesSee all

Charles Bourgault and Sarah Moin

August 19, 2025

Spencer Feingold

August 18, 2025

Jon Jacobson

August 14, 2025

Ruti Ben-Shlomi

August 11, 2025

David Timis

August 8, 2025