What disasters teach us about avoiding mistakes at work

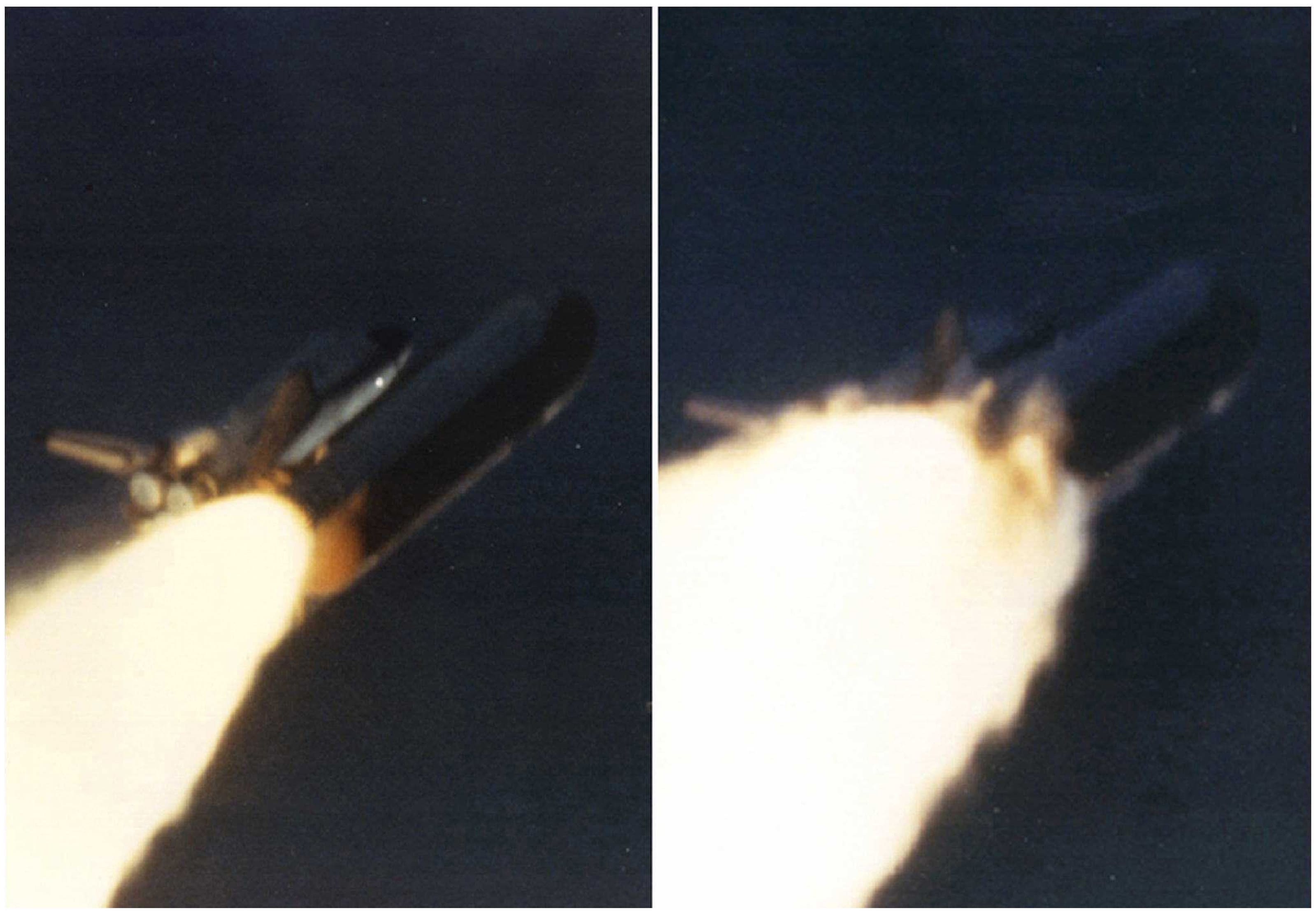

Every tiny detail needs to be right for a project as complicated as a shuttle launch Image: REUTERS/Pierre Ducharme

In the late morning of the 28 January 1986, the space shuttle Challenger took off in Cape Canaveral, Florida, only to break up midair within two minutes, and come crashing down into the Atlantic Ocean. All seven crew members were killed. The multimillion-dollar project went tragically and disastrously wrong due to an inexpensive rubber O-ring seal, which had failed due to the unusually low temperature on that day.

In the tale of the Challenger crash, the economist Michael Kremer saw a powerful metaphor to describe the nature of work. Most production processes, he observed, require a sequence of tasks and activities to successfully create a final product. A single mistake in a single task can severely reduce the value of the final product. A space shuttle packed with cutting-edge technology, painstakingly assembled and tested by the world’s leading experts, became a catastrophic failure due to the weakness of a simple O-ring seal.

Expanding on this insight, the economist David Autor observed that most jobs are O-ring jobs and that their importance can massively increase as the humans performing them are sided by high-performing, AI-powered partners.

In other words, individual tasks are critical to the completion of some larger job, alongside the tasks performed by others. As most jobs require teamwork and close cooperation, the weakest link can therefore reduce to zero the effectiveness of the group as a whole. Moreover, the quality and value of each contribution depends on that of others. If you work in a system where most of your colleagues perform poorly, the final product will be of little value, regardless of whether you make any mistakes.

If the shuttle had been poorly designed and built, the failure of the O-ring would have been irrelevant. However, for a craft designed and built to the highest standards, the quality of the O-ring was ultimately critical. So as soon as the reliability and quality of every task performed by others increases, the importance of your task increases as well. If we work in an organization that constantly aims to “raise the bar”, increasing the quality of services and products it provides, we need to pay attention to the O-ring.

As the Fourth Industrial Revolution – a wave of digital-era disruption – radically transforms systems of production and the nature of work, it is important to heed the lesson of the O-ring.

As workplace applications of Artificial Intelligence (AI) become more effective and efficient, humans are increasingly concerned about being made redundant. This need not be the case. According to a study by McKinsey, about 45% of the activities performed by humans at work can comfortably be automated – that is, performed by existing and tested technologies, which do not require human input. However, fewer than 5% jobs can be entirely automated. Most jobs, instead, will be redefined and transformed, as some of their typical activities become automated. In the process, these jobs will become increasingly critical to overall success – much like the O-ring.

Two recent reports of the World Economic Forum explore this matter further, the first suggesting how workers whose jobs are especially likely to be automated could transition towards new, well-paid and stable occupations.

The second explores eight possible scenarios for the future of work and elaborates on how to prepare for each.

Both concur that re-skilling is a critical element to prepare for the kind of O-ring jobs that define the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Re-skilling is coupled with another imperative. With expanding life expectancy, we cannot afford to stop learning when we are in our mid-20s. With approximately 40 to 50 years of active professional life ahead of us, we need to become learning machines to “win” against machine learning.

These changes entail three specific challenges that leaders have to explicitly address in the nearest future to keep their workers healthy, engaged and productive.

Making workers agile. Evolving occupations entail a need for humans to rapidly acquire new skills and competences and to learn how to perform tasks that are distinct from those required by their current occupations. The fast pace of change of the Fourth Industrial Revolution rapidly makes skills obsolete and therefore creates a constant pressure to upskill and re-skill. Organizations need therefore to implement serious learning plans for their employees and provide meaningful opportunities to them to expand their skills and competencies through, for example, mobility plans, projects, new initiatives, coaching, development assignment and mentoring. If your organization does not invest at least 3% of the overall costs of staff salaries in learning and upgrading skills, it could be obsolete within three to five years.

Helping workers meet demanding standards. As AI-powered appliances consistently and reliably perform up to 45% of work tasks, the importance of humans, like that of O-rings, will increase. The increased standards of performance required to match that of robots and algorithms – depending on newly acquired skills, for which workers have not accumulated much experience – and the threat of mistakes that lead to critical failures will put increasing pressure on humans.

Managing new, mixed teams. New AI-powered systems are no longer only tools under the control of humans. Learning machines act as peers, when they perform the same tasks as humans – or at least the predictably repetitive parts of those tasks – or even as managers, when they assign tasks to humans in order to optimize their output. Working alongside an artificial colleague or taking orders from an artificial manager puts pressure on humans to adapt to new styles of communication and collaboration.

Indeed, the critical leadership challenge for the Fourth Industrial Revolution is ensuring that interconnected groups of people and artificial systems cooperate to collectively achieve what neither could achieve individually, in a competitive and social context that keeps evolving at increasing speed. Lastly, we need to remind ourselves that, regardless of who is performing the task – robot or human – we must keep our moral compass based on the values we have and what we stand for. This is one task that cannot be delegated or managed by AI.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Future of Work

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Jobs and the Future of WorkSee all

Till Leopold

November 14, 2025