The so-called 'leftover women' in China contribute more to GDP than in the US

In China, women who are in late twenties and single have been termed as 'leftover women'

Image: REUTERS/Joe Tan

Stay up to date:

Gender Inequality

There are 7 million 'leftover women', a term used for urban single ladies between the ages of 25 and 34, in China. The part these women play in the Chinese miracle is sometimes overlooked, even though these young, urban, well-educated and single Chinese women are among the greatest contributors to their country’s growth.

Indeed, their contribution comes with a price, writes Roseann Lake in her new book Leftover in China: “[O]n paper, these women are pushing toward the upper echelon of the self-actualization pyramid. But as unmarried women, they teeter toward the bottom half of what is socially acceptable in China.” So exactly what role should the “leftover women” play in China’s economy and society?

Role of leftover women in China

First off, it’s important to note that women weren’t always (allowed to be) the economic motors of China, as Lake writes: “Until 1906, most Chinese women had their feet bound. Until 1950, they were sold in marriage to the highest bidder.”

But after this tough start, two side-effects of communist rule dramatically changed the country’s gender dynamic.

During Mao’s Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, China’s female employment rate became one of the highest in the world, as women became “sexless comrades”, labouring shoulder-to-shoulder with men. It was hardly a glamorous promotion but it did, for the first time ever, put many women on the same level as men.

Contribution of China's one-child policy to the emergence of leftover women

The one-child policy implemented under Deng Xiaoping was the second reason for women’s rise, though again this wasn’t precisely a feminist policy. Boys were preferred to girls as the only child, especially in rural areas, leading to tens of thousands of infanticides per year. But the girls who were accepted did not have to compete with brothers for resources and attention and were able to blaze a trail that previous generations of women could not, as Ye Liu, senior lecturer in international education at Bath Spa University tells Times Higher Education.

The result is that, as in many other countries around the world, girls started outperforming boys in school: today, almost 53% of the top-scoring students across China’s 31 provincial-level regions are female, according to Lake’s book, and Chinese women have been the dominant gender in colleges for several years.

The number of female graduates in university might be even higher were it not for the discriminatory practices implemented by many (top) universities: women often need to score higher grades than men to gain admission.

Crucially, this female “dividend” now plays out in the economy.

China's female dividend

Dr Kaiping Peng, a psychology professor at Tsinghua University, estimates that some 70% of the local employees of international corporations in Shanghai’s Pudong or Beijing’s Central Business District are the so-called Chinese leftover women. It is only anecdotal evidence but those of us who have been there, myself included, are likely to nod in agreement with that estimate.

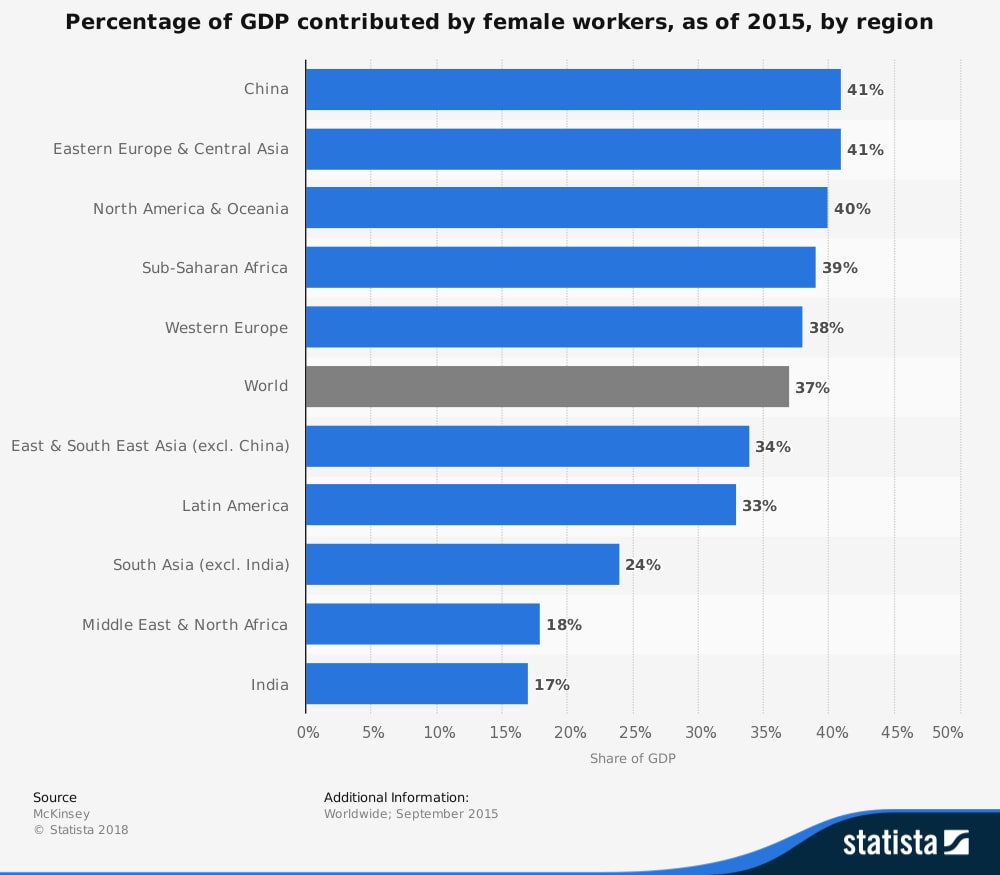

On aggregate, women now contribute some 41% to China’s GDP, a higher percentage than in most other regions, including North America. On the production side, they represent the best of China’s brain power and are propelling their country to new growth. On the consumption side, they buy millions of articles on Taobao and turned Alibaba’s Singles’ Day into the world’s most valuable day for retailers.

But here’s the catch: the rest of the country hasn’t quite caught up, Lake writes. While the economic realities of China have changed, often thanks to this new generation of women, the cultural expectations of Chinese society, by and large, have, for these women, remained the same. Getting a great education and finding an upper-middle-class job is all well and good but, once they hit 25, Chinese women are expected to marry and live the Chinese equivalent of Sois belle et tais toi.

Dilemmas behind the leftover women

Leta Hong Fincher, who is credited with coining the English term “Leftover women”, asserts that the leaders of modern-day China still reduce women to their roles of reproductive tools for the state, dutiful wives, mothers and baby breeders in the home. As for men, their function is still that of the main breadwinner. Therefore, to make a wedding worthwhile, a woman best marry someone who is wealthier, better educated and more accomplished; in short, she should marry up.

But most sons in rural China did not pursue an education, stayed behind in the village to look after the estate, and were more likely to miss the economic miracle. They come up short on the expectations of “a house, a car and cash”, not to mention a university degree. They often end up staying single or marrying “imported” brides from Cambodia and other countries in South-East Asia.

As for the urban, educated women, they face a Catch 22 too: they’re expected to marry up and to marry young, but live in cities in which the average man is less educated and less wealthy than their parents’ expectations. After 23 years or so of pursuing education, they want to give their own career a go too. Therefore, despite the general shortage of women, 7 million of those who are young and urban will not get married. For some it’s a cause for concern because of unfulfilled societal pressures; for others, it’s empowering.

For China as a whole, however, the phenomenon of “leftover women” is problematic. On the one hand, China really needs women to participate in the workforce, as they’re better suited to China’s future economic growth model; on the other, the country also needs its women to (marry and) have children, because a demographic boomerang is about to hit the country in the face - China is rapidly ageing.

China’s neighbours Japan, Korea and Singapore have all faced this problem before and they’re still struggling with its consequences. In Japan, which vies with Germany for the title of world’s oldest population, Japanese women face a tough reality in work and marriage: many young women don’t get married or have children but discrimination of women in the workplace continues.

For China, it would be best to avoid this fate and to do so it may do well to promote more gender equality in the home and at work. For starters, it could change customs and laws regarding employment, as many companies, both private and public, discriminate based on gender and marital status. Instead of harnessing its greatest economic asset, China hurts it.

Secondly, China’s lawmakers could do their part to change gender roles in the home also. A good place to start would be to treat the husband and wife as equals in matters of marriage. Presently, for example, a house is still most often registered under a man’s name and inheritances more often favour sons over daughters and wives.

Ultimately though, it is up to China’s people to change their views on the optimal, prospective husband and wife. Until these leftover women can easily “marry down” or combine marriage with work, the Middle Kingdom won’t reach its full potential in either offspring or economic growth.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Equity, Diversity and InclusionSee all

Claire Poole

June 24, 2025

Julia Hakspiel

June 17, 2025

Gayle Markovitz, Kate Whiting and Pooja Chhabria

June 12, 2025

Kim Piaget and Yanjun Guo

June 12, 2025