How living with HIV and Aids has changed, more than 30 years on

Medicines have improved, but 1 million people still die of Aids-related illnesses every year. Image: REUTERS/Navesh Chitrakar

The shadow of Aids has hung over the world for over three decades but a lot has changed in that time. To a large extent the beast has been tamed, turning what was once a virtual death sentence into a treatable condition.

Since the Aids pandemic took hold in the 1980s the disease has killed an estimated 39 million people and decimated whole communities.

The fight to contain the spread of HIV – the virus that acts as a catalyst for Aids – has led to numerous medical breakthroughs and helped raise global awareness of the dangers associated with it.

AIDS-related deaths worldwide by region in 2017

However, as the chart shows, despite advances in treatment Aids still kills almost 1 million people worldwide each year. People diagnosed with HIV in the developing world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, are often unable to afford the high cost of new treatments.

Prevention is better than cure

One of the latest weapons in the battle against HIV/Aids is an antiviral treatment called pre-exposure prophylaxis, abbreviated to PrEP.

Taken daily, the oval-shaped blue Truvada pill helps prevent the spread of HIV. Trials of Truvada in Australia have seen new infections drop by almost a third of pre-trial rates. The treatment has tested 90-99% effective in curbing the spread of HIV.

The Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommend expanding the use of Truvada. However, the drug’s high costs of up to $1500 a month put the preventative treatment beyond the reach of many.

Breaking the taboo

The rapid spread of the global Aids epidemic was due in part to a lack of knowledge of how the HIV virus is transmitted.

It was the early 1980s when the disease began to appear in the US. The first known cases involved previously healthy, young gay men, who had succumbed to rare and aggressive forms of cancer and pneumonia. It wasn’t long before an assumption was made that this new illness was linked with gay communities – one of its earliest names was GRID, which stood for gay-related immune deficiency.

It would take several more years for the virus to be correctly identified and for its transmission and development to be understood. That led to health education campaigns advocating safe sex, and the development of needle exchange programmes to combat needle-sharing among drug addicts.

Even though it is known that HIV/Aids can affect anyone, regardless of sexual orientation, gender or ethnicity, the stigma has not disappeared completely. In countries that are less culturally tolerant or are openly hostile to non-heterosexual ways of life, the disease is still seen as something to be feared, reviled and even ignored.

These perceptions prevent people getting tested regularly and hamper ongoing efforts to contain the virus. Recent increases in HIV infection rates in Russia have been blamed on these kinds of negative attitudes.

Can we achieve an AIDS-free world?

There is now more support and understanding for people living with HIV/Aids, though this is not the case everywhere.

The life expectancy of people with HIV/Aids has massively improved over time. The death rate stood at 78% between 1988 and 1995, and dropped to around 5% between 2005 and 2009.

Today, with early use of antiretroviral drugs, people with HIV can expect to have normal life spans. Moreover, they can also expect to be able to lead normal lives. The World Health Organization recommends people infected with virus are prescribed a combination, or cocktail, of different antiretroviral medications. Drugs such as tenofovir, emtricitabine, lamivudine, efavirenz are combined to combat the patient’s viral load – or, put simply, the amount of the virus in the body.

Although not a cure, antiretroviral treatment can reduce the viral load to undetectable levels. Studies have found that HIV+ people with undetectable viral loads will not pass the virus on to others.

But will we ever be able to confidently predict that an Aids-free generation is in sight?

UNAIDS, the United Nations agency responsible for coordinating the global fight against the epidemic, points out that while great strides have been made, there is still work to be done.

The next goal for HIV researchers is a reliable vaccine. Studies and tests are already underway and although early indications are encouraging, there is no timeframe for a widely available HIV vaccine. A cure is perhaps even less likely, due to the way the virus replicates in the infected host’s body. Like any virus, HIV infects individual cells, and hijacks their DNA, which it then uses to replicate itself.

HIV, however good it is at spreading, it less good at making precise copies. The mutations in its replication process mean it is extremely difficult for the body’s immune system to target it precisely.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

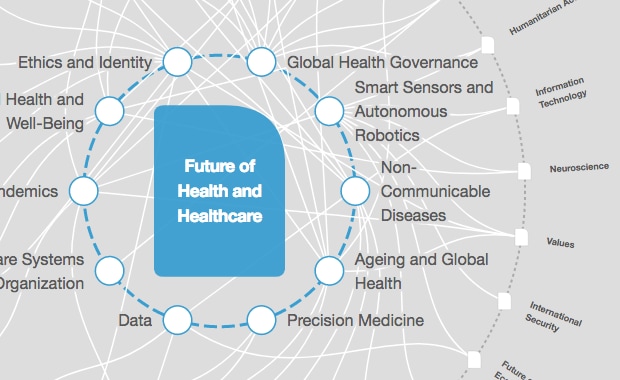

Health and Healthcare

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Health and Healthcare SystemsSee all

Michelle Meineke

November 22, 2024