Understanding the gender gap in the Global South

Mobile phone penetration is broadly aligned with GNI per capita

Image: REUTERS/James Akena

Stay up to date:

Digital Communications

Despite there being no accurate data available at the global level to support claims currently being made in various gender and information and communication technology (ICT) indices, it is important to recognise the relevance of equality in access and use of the internet to social and economic inclusion in the contemporary world.

Central to the call for digital equality are claims that the internet has the potential to accelerate progress in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. SDG 5B specifically identifies the enhanced "use of enabling technology, in particular ICTs, to promote the empowerment of women”, SDG 9C is concerned with promoting universal ICT access and SDG 17.6 with promoting global collaboration on and access to science, technology and innovation.

As explained in an earlier blog highlighting the findings of the AfterAccess 2017 survey, without undertaking the national representative surveys it is impossible in the predominantly pre-paid mobile environments that characterize developing countries to get sex disaggregated (or any other disaggregated - rural/urban, income) data from the supply-side data provided. Although data analytics from social networking platforms such as Facebook or search engines such as Google can quite accurately predict the sex of a user, such analytics are unable to establish the reasons for the large numbers of people not online in developing countries, or their gender, location, education or income levels. Acknowledging the challenges with the supply-side data used for ICT statistics within the UN system, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) responsible for ICT statistical standards provides training and supports the undertaking of national ICT access and use surveys.

With ICT targets underpinning several of the SDGs, it is important to understand whether these benefits are evenly distributed between men and women. Ending discrimination against women and girls is therefore not only a human rights issue, but is also central to harnessing all available human resources for sustainable economic growth and development. It is essential to understand the drivers of digital inequality, and which women and men experience it, as neither are homogenous groups.

Likewise, it is equally important to understand the less positive implications of ICTs for women - for instance, the impact of surveillance or online abuse on women’s rights. Those women who are located at the intersection of other factors of exclusion, such as class, race and in particular marginalized locations, whether rural areas or city slums, experience even greater digital inequality than aggregates of women whether at the global, national or local level.

Besides these methodological and analytical challenges, other issues hampering efforts to understand and address digital inequalities better include: the ways in which not only gender indicators are defined, but also the relevance of ICT indicators against which gender inequality is being assessed in predominantly prepaid mobile markets in the Global South; the relevance of existing targets to address gender access discrepancies without baselines on which to base them; the practical challenges of rigorous and timely data collection; and those associated with global comparability.

The survey results contribute to filling some of the information gaps that these challenges produced in the Global South. In doing so, they build on previous studies attempting to grapple with the challenge of accurate data collection, including gender disaggregated data for the purposes of informed policy interventions in developing and emerging economies.

The findings of an ICT access and use survey undertaken by DIRSI, LIRNEasia and RIA across 16 countries in the Global South during 2017 (with the exception of Myanmar, which was during 2016) goes some way to addressing some of the problems identified above. As these are nationally representative and survey those offline and online, the data can be disaggregated based on sex to provide an accurate picture of gender differences in access, and importantly of use in pre-paid mobile environments.

They also include questions on income, education and expenditure that allow for the modelling of data that enables the identification of the real factors of gender inequality in a way that descriptive statistics cannot. This goes some way to nuancing conceptions of women and men as homogenous groups that have plagued much of the quantitative research and grand claims in this area, and it enables the location of gender at the intersection of other factors of inequality such as rural location, class, age and race.

As the previous blog demonstrated, mobile phone penetration is broadly aligned with GNI per capita. Figure 1 below shows that this pattern is broadly true of the gender gap also. Overall, the five Latin American countries surveyed, together with South Africa, are the richest among all the countries surveyed and show the lowest gender gap. In contrast, the poorer African countries show high gender disparity in mobile, but particularly in internet, use.

However, these disparities are lower than in some higher-income Asian countries, where we see some of the greatest disparities in income. The GNI per capita in India and Bangladesh is more in line with that of Ghana and Kenya, but both countries, together with Tanzania (which is also among the poorest countries) have much lower gender disparities than in the Asian countries surveyed.

However, we see interesting anomalies. Though Argentina’s GDP per capita at over $10,000 is more than double the other top performers that cluster around $5,000, including Colombia, Argentina performs only marginally better than Colombia in terms of mobile phone ownership gender parity. Although overall mobile penetration is lower in Colombia than in its Latin American counterparts, it has gender parity in mobile ownership. South Africa, which has similar average GNI per capita to the Latin American countries, despite having one of the highest income disparities in the world, has more women who own mobile phones than men.

Of all the countries surveyed, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh have the highest gender gaps in mobile phone ownership (Figure 1). Together with Rwanda and Nigeria (which has by far the largest population in Africa, similar to that of Bangladesh) they also have among the highest gender gap in internet use (Figure 2). These populous nations therefore account for a large number of unconnected women in the Global South.

These gender gaps exceed those in some of the least developed countries in Africa, where the highest gender variance in mobile ownership is in Mozambique and Tanzania. The biggest internet gender gap of all the countries surveyed is in Bangladesh, closely followed by Rwanda and then India, Mozambique and Nigeria. The gender gaps in Rwanda and Mozambique are double those of other developing African countries.

Besides South Africa, of the African and Asian countries surveyed, the only country within range of the Latin American countries is Kenya, with a relatively low mobile phone gender gap of 10%. This correlation between higher mobile phone penetration and lower gender gap is also reflected in Kenya, where the mobile phone penetration rate is in line with the lower-middle-income countries of Latin America. With a similar GNI per capita in 2016 to that of Kenya, Ghana follows with a gender gap of 16%. Nigeria, with a GNI per capita twice that of Kenya and Ghana, has a mobile gender gap of 18% and a penetration rate similar to that of Cambodia.

Cambodia has the lowest GNI per capita (and penetration rate) of the countries surveyed in Asia, more in line with Ghana and Kenya. Despite this, Cambodia’s gender gap at 20% is by far the lowest of the Asian countries surveyed in relation to mobile phone ownership and internet access. Its internet gender gap is a good 15% below Pakistan and Bangladesh and 25% below India. With the highest GNI per capita of nearly $2000 in 2016, India has a staggering 46% mobile phone ownership and 57% internet gender gap.

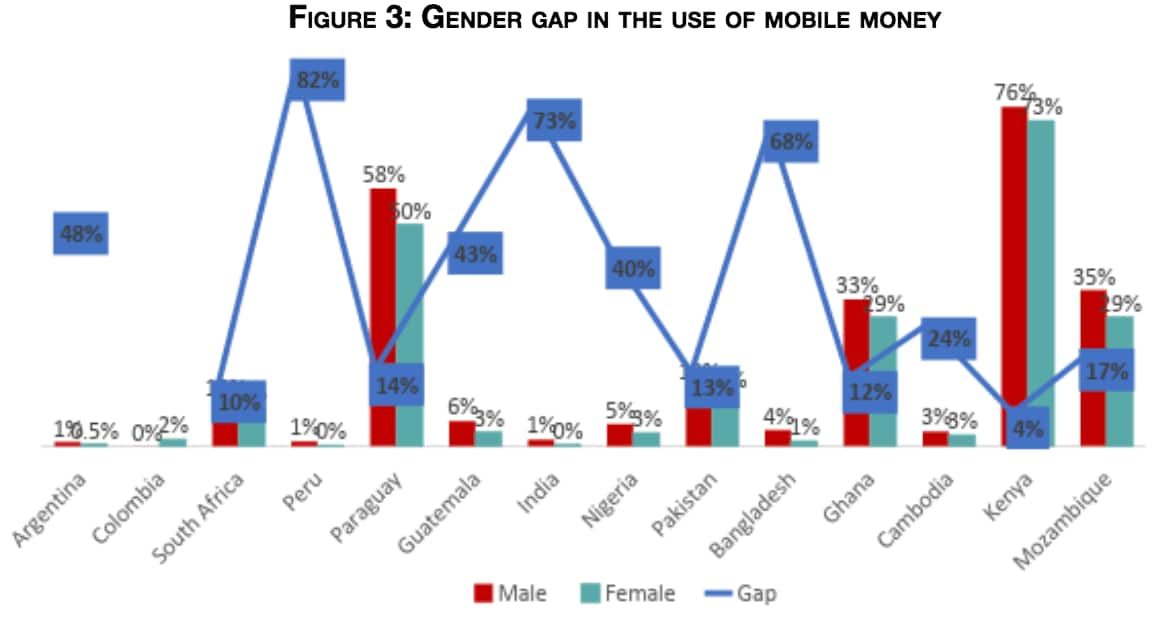

The use of mobile phones for mobile money transactions is minimal and almost negligible in most of the countries surveyed. However, we do still see a gender gap in countries where mobile money is used (see Figure 3). In Latin America, it is only in Paraguay that more than half of men and half of women make use of mobile money. Asia makes the least use of mobile money.

Even in Pakistan, which stands out among the Asian countries in terms of mobile money use, only 13% of men and 12% of women use this service. While much has been written about the demonetization of currency notes of certain denominations in India and the resulting claim that the use of mobile money has skyrocketed, our numbers do not show such use.

In Africa, especially East Africa, mobile money is widely used. With the now internationally renowned mobile money transfer service, M-Pesa, which makes up an overwhelming majority of the mobile money market share in Kenya, it is not surprising that over 70% of people in Kenya use mobile money. Yet, there is still a 16% gap between men and women using mobile money, in favour of men.

Regression analyses of the data at the regional level shows that sex, income, education and location are all significant determinants of whether people use the internet. In terms of sex, women have a lesser chance of using the internet, which supports the descriptive findings that women lagged behind men in internet use in all seven countries surveyed in Africa. People with higher levels of income and education are more likely to be online than those with lower income and education levels across all regions. Also, those in rural areas stand a lower chance of being connected.

These may be contributing factors to the gender disparities in internet use, as more women tend to fall into these categories. Although the modelling shows that the main determinants of this digital gap are education and income, these are themselves likely to be determined by cultural and social factors, which are more likely to be captured by qualitative research.

From a policy perspective, it is clear that demand-side interventions that address not only affordability but also e-literacy and education more widely are as critical to digital inclusion as supply-side connectivity measures. Moreover, as the Asian and Latin American cases have shown, deeply entrenched factors, such as social and cultural norms, as well as attitudes towards women, need to be taken into account when analyzing women’s access to and use of ICT.

Although further investigation is needed to understand this better, technology adoption and diffusion through commercial models reflects early adopters being more educated, high-income users with low levels of gender variance in societies and economies that do not constrain the participation of women. As more users come online, the disparities in ICT access and use reflect disparities between women and men in relation to education and income (employment), but as prices of devices and services come down and poorer people (disproportionately women) come online, markets begin to saturate and the figures for men and women tend to equalize.

Initiatives to make internet use more affordable, including the reduction of taxes and duties on devices and taxes on social networking to stimulate demand for local content and thus lower the income barrier for men and women to come online, would at the same time reduce the gender gap in internet access as more people use it.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Equity, Diversity and InclusionSee all

Katy Talikowska

August 18, 2025

Jürgen Karl Zattler and Adrian Severin Schmieg

August 18, 2025

Katica Roy

July 23, 2025

Elena Raevskikh and Giovanna Di Mauro

July 23, 2025

Veronica Frisancho

July 22, 2025