The first new university in the UK for 40 years is taking a very different approach to education

Future proof.

Image: REUTERS/Toby Melville

Stay up to date:

Education

What role should universities play in equipping the workers of the future to solve the world’s most pressing problems? And, as we approach the 2020s, should we rethink the way education puts subjects into silos?

The answers to these questions are being explored by an innovative new concept in higher education coming to the UK in 2020.

The London Interdisciplinary School (LIS) - the first new university in the UK for 40 years - is taking a new approach to teaching and learning, with a cross-curricular focus on tackling the most complex problems facing the world.

Co-founded by Ed Fidoe, co-founder of School 21 and former McKinsey manager, LIS will award a Bachelor of Arts & Sciences (BASc) degree (pending approval this year), which involves 10-week paid work placements each year to ensure students are workplace ready.

In an interview, Fidoe told the World Economic Forum that LIS is flipping academic learning on its head: “The big shift we’re making is to combine knowledge through disciplines to tackle problems.

“If you start with disciplines, you immediately have walls you have to break through, so we’re starting with the problems and then backfilling the academic learning. We’re trying to turn theory into action.”

Tackling problems

LIS says it will promote learning through “real-world challenges” and includes knife crime - something that’s risen sharply in the UK since 2014 - in it’s list of potential topics.

Rob Jones, Chief Superintendent of London’s Metropolitan Police Service, is part of the university’s advisory group, along with leaders from companies including McKinsey, Virgin and Innocent Drinks.

Other issues the institution will look at range from designing a tool for companies to track palm oil supply to the ethics of editing mosquito genes using CRISPR technology to eradicate malaria - combining probabilistic thinking with international relations, ecosystems and genome editing.

The idea for LIS came about in response to what Fidoe saw as a restrictive ‘single-subject culture’ that dominates at universities in the UK and elsewhere because they’re structured around research, which is organized in single disciplines.

“The world is more connected and complex than it’s ever been and it requires people to think in systems rather than narrow silos,” says Fidoe.

“We do need some people to go into very narrow fields and become experts, so we shouldn’t do away with subjects.

“But students have to understand how this stuff fits together in a system, because it’s increasingly how the world is working, how supply chains are set up and communications systems work. If something happens over here, there are all these consequences somewhere else.”

Shifting sands

While the opportunity to combine big-name work placements with study may appeal to some students, the new institution will be competing for students and fees with some of the world’s top universities, including Oxford, Cambridge and London’s Imperial. With tuition fees of around $12,000 a year, LIS will need to convince potential students that it can deliver value for money.

One criticism published in the Guardian newspaper also questioned whether companies or organizations such as the police should be involved in curricula, arguing instead that students should learn to be clear-eyed and critical of the interests at stake.

Employers are also increasingly recruiting directly from school, recognising that academic skills don’t always match up with determination, flexibility and a strong work ethic. Job-search firm GlassDoor has recently compiled a list of companies that are no-longer demanding a degree, and these include Apple, Google, Hilton and EY.

And IBM’s CEO Ginni Rometty spoke at this year’s World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos about the need for companies to develop a different mindset when it comes to recruiting, looking to grow skills on the job rather than hiring people with degrees.

There has also been a significant fall in the number of university applicants in the UK over the last two years, as the chart below shows.

Skills for tomorrow

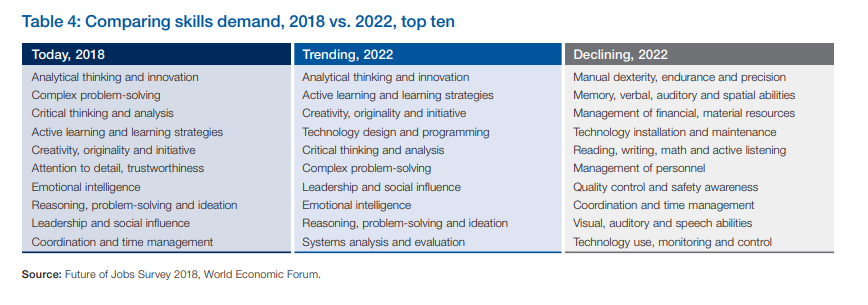

The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs 2018 report projects that, by 2022, besides proficiency in new technologies, ‘human’ skills such as creativity, originality and initiative, critical thinking, persuasion and negotiation will retain or increase their value in the face of increased automation. Attention to detail, resilience, flexibility and complex problem-solving will also be key.

“Emotional intelligence, leadership and social influence as well as service orientation will also see an outsized increase in demand relative to their current prominence,” it says.

Besides its problem-based curriculum, LIS will also teach students the key skills they need to survive in the modern world: including research methods, tech skills like data analytics and coding, and ‘softer’ skills like interviewing, critical analysis, creativity and collaboration.

“People understand the importance of STEM subjects, but now they’re increasingly saying we need to combine this with an understanding of psychology and humanity, art and design,” says Fidoe.

“Being able to combine those things is something that machines will find very hard to do but humans need to be able to.”

There is certainly a need for a broad range of skills to meet the needs of tomorrow’s workplace.

But is it not yet clear whether students will want to take a punt on a different style of education, or whether they will continue to favour more traditional institutions or even decide to skip a degree altogether.

And Fidoe admits that the first batch of 120 students will need to be bold and willing to go on an adventure: “It’s not for the faint-hearted - they’re going to be part of a big project that we’re building, this new university."

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Education and SkillsSee all

Stacy Greiner

July 1, 2025

Jean Daniel LaRock and Ashley Hemmy

June 23, 2025

Roberta Vicente Barreras

June 19, 2025

Steven Sim

June 10, 2025

Natalia Kucirkova

June 10, 2025

Morgan Camp

June 6, 2025