Intelligent - rather than smart - cities can address the roots of urban challenges

An intelligent approach to cities is a reflexive and responsive way to address urban challenges. Image: REUTERS/Hyungwon Kang - GF20000042633

The term “smart city” has gained in popularity, but the label still conjures the use the technologies to solve operational problems. Rather, cities are complex and need intelligent, transformative and engaged efforts.

Sustainable development goals such as in health, housing, education, energy, hunger and happiness have always been urban issues. The 1994 European Cities and Town Charter on Sustainability says it well:

“in the course of history, our towns have existed within and outlasted empires, nation states, and regimes and have survived as centres of social life, carriers of our economies, and guardians of culture, heritage and tradition… Towns have been the centres of industry, craft, trade, education and government… sustainable human life on this globe cannot be achieved without sustainable local communities.”

”Aside from revenue distribution, eliminating silos in favour of a collaborative governance model with shared responsibility would help. For example, the question of waste requires action on several fronts — more citizens, businesses and organizations involved in designing and implementing a holistic ecosystem.

Smart city development incentives

The challenge for policy makers and governments is how to stimulate the development of intelligent collaborative planning processes given digitalization, the fast pace of technological change, global warming and accelerating sustainable development needs on one hand, and the reticence to organizational change and change in our individual lives in the other.

There are questions on the value of top-down or bottom-up approaches. China and Europe have different systems — one is top down and the other bottom up — yet are achieving, collaborating and learning from one another.

There are questions around focused or flexible approaches. The United States issued a smart city challenge with a focus on mobility while Canada’s approach to smart city development invited communities to choose their challenge and its solutions.

A key theme for cities these days is the importance of collaboration and partnerships outside its own borders. In a chapter of the forthcoming book, Innovative Solutions for Creating Sustainable Cities, Sylviane Toporkoff and Gérald Santucci point out that at the turn of the 21st century, the pendulum swung more visibly from competitive cities to cooperative cities, particularly in Europe.

The phenomenon started with the European Union Fourth Framework Programme, to accelerate innovation and growth. It was followed by a number of collaborative initiatives including Eurocities and the Major Cities of Europe. This reflected the recognition that cities had individual problems and different ways to solve them, but still needed to collaborate, co-create and share rather than only compete. Differentiation and competition have their place, but so do equity and efficiency.

Canadian experience

The Canadian Smart Cities Challenge, announced in 2017, invited demonstrations of approaches that used data and networked technologies. Participating communities were asked to engage with their citizens to propose solutions for a significant local or regional challenge. Communities across Canada held hundreds of consultations with their citizens and reported on the value of the exercise. Partnerships and collaborations were encouraged and all applicants had internal stakeholders prepared to contribute. Interestingly, a handful chose to create a network of several communities to address common problems.

As a special advisor to the Smart City program and an academic, I reflected on and classified the 130 eligible applications into three streams:

Forty one per cent related to improving citizen well-being through health (physical, emotional), increased community engagement and safety. The use of mobile applications to disseminate information, monitor with sensors and cameras and self-management were popular ideas. Some projects proposed to develop networks for improved access to housing and food. Others suggested new multi-generational, multicultural business networks to mentor target groups, improve the sense belonging and reduce isolation.

Thirty one per cent wanted to improve the environment and mobility through new energy sources. These projects proposed managing energy consumption, traffic, offering multi-modal transportation, promoting bicycle use and facilitating electric vehicle use with charging stations. Others examined autonomous transit, waste management and environmental monitoring.

Twenty eight per cent were focused on economic development, including support systems for start-ups, attracting knowledge workers and technology industries, designing new educational programs and retrofitting specific sectors of the economy with digital tools.

Four projects received funding. The themes of the funded projects included: access to food and the development of a circular economy; sharing community data to support development; household and urban energy management; health monitoring and system improvements; Indigenous culture preservation; initiatives in sustainable transportation and mobility; environmental risk management; and child and senior safety (such as reducing risks for seniors and establishing systems for the healthy development of youth).

European experience

The European approach encouraged organizations to partner, co-create, share, model, innovate and duplicate. There are over 100 individual city projects listed on the European Smart City website. Projects are classified under six areas: smart economy, people, governance, mobility, environment and living. It is the pursuit of these six areas in combination that begins to move cities from smart to intelligent and the criteria encourages cities to progress along several lines.

Sharing knowledge and resources is key. Pilot projects such as the Issy Smart Grid in suburban Paris, integrating the local production of renewable energy, need to be replicated and are widely disclosed.

Collaborative approaches between cities are becoming a new norm and yield interesting innovations and opportunities - for example, seven municipalities under URBiNAT are regenerating and integrating social housing using nature-based solutions. Another example is Fabrication City, where 28 cities are developing sustainability through circular economies and strengthening local entrepreneurship.

Cities need to move from conventional ways of managing from a focus on immediate fixes to smart and intelligent approaches that look at solving root causes. I am convinced that the lessons learned from smart and intelligent urban projects worldwide can open new avenues to create healthy, sustainable, and happy places for everyone.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

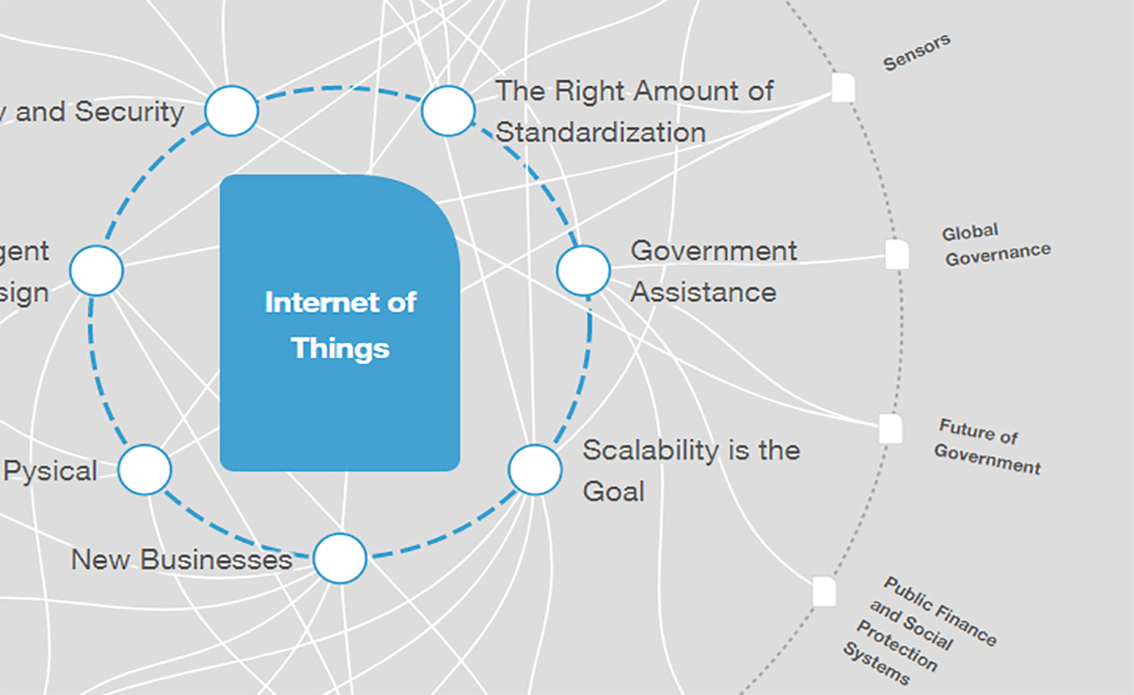

Internet of Things

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Urban TransformationSee all

Emi Maeda

December 27, 2024