Can we use AI to make industrial systems safer? A young scientist explains

An oil tanker unloads crude oil at a terminal in Zhoushan, China. Image: Reuters

As part of our series exploring the edges of scientific research, we caught up with World Economic Forum Young Scientist Olga Fink, a professor of intelligent maintenance systems at EHT Zurich, who is developing intelligent algorithms to improve the safety and reliability of complex industrial assets

What is the big problem you're trying to solve?

The ultimate goal of my research is to improve the performance, safety and availability of industrial assets and critical infrastructure, and make their maintenance and operation more cost-efficient. Recently, complex engineered systems have been tightly monitored by a lot of condition-monitoring devices. My research focuses on developing intelligent algorithms that learn from these massive and heterogeneous sets of condition-monitoring data and predict the faults before they occur - even in cases where the systems haven’t experienced any faults yet. One of the major challenges here is to make the algorithms generalizable and their development scalable.

What is the big idea you're trying to use to solve it?

There are several underlying ideas. One of them is to develop artificial intelligence algorithms that are not only applicable to one specific system but that enable the operating experience and fault patterns to be transferred between the single systems of a fleet. It is similar to when someone who speaks Portuguese wants to learn Spanish: he or she will not start talking to a Spaniard in Portuguese, but will also not start learning Spanish from zero - they can transfer some of the underlying concepts, grammar and vocabulary.

One of the other directions that we are following is to combine engineering knowledge and artificial intelligence algorithms to make the best use of both worlds.

How would you explain that to a 5-year-old?

Our task is like that of a medical doctor with the difference that our patients are complicated industrial assets such as power plants, ships’ engines and trains. Since our patients cannot talk to us to tell us that they are not feeling well, we rely on condition-monitoring systems that collect evidence on the health condition of the system. We then use these measurements to detect when a system is starting to get ill, diagnosing the cause and predicting how long the system can still be safely operated. The ultimate goal is not only to predict what is going wrong but also to prescribe to the system how it should be operated to extend its useful life, similarly to the prescription of a doctor when he advises a patient to adapt their diet and to exercise more to extend their lifetime.

The most difficult part has been to find datasets from real applications that are suitable to demonstrate the effectiveness of our approaches.

It is not shocking but probably surprising: our biggest challenge arises from the fact that safety-critical systems are very reliable and do not experience many faults. This makes it difficult for us to learn from the data, but also to verify the developed solutions. If we wanted to wait until we collected enough faulty patterns to learn from, we would need to wait for hundreds of years (and depending on the size of the fleet, even for thousands).

Another surprising fact is that even though large amounts of data are collected for many applications, they are not pro-actively used in many cases.

The last piece is that there is no magic behind artificial intelligence algorithms. They can only learn what is contained in the data. However, it may be hidden and not obvious.

When I was a child, I wanted to become a doctor. When I grew up, my interests changed and I discovered that my love for math was bigger, and I became an engineer. But at the end, I became a doctor for machines.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

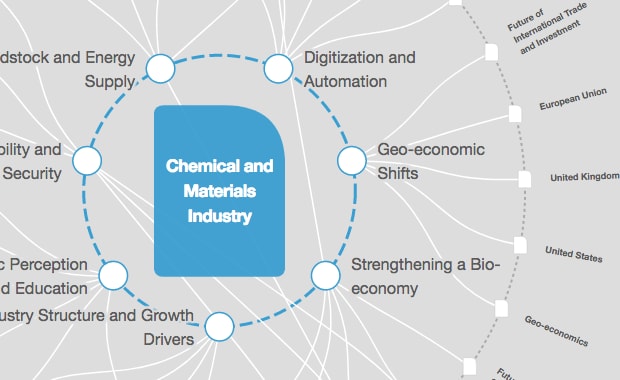

Chemical and Advanced Materials

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.