This is how trees could help solve the climate crisis

'To stop climate change, we must draw down the carbon already emitted into the atmosphere'

Image: REUTERS/Beawiharta

Stay up to date:

Future of the Environment

There are 300 additional gigatonnes of carbon in the atmosphere as a result of human activity since the start of the industrial revolution. As the climate warms, the activity of micro-organisms in the soil increases and this further increases carbon emissions. Given that the vast majority of the Earth’s carbon is stored in our soils, these so-called feedback loops are beginning to speed up climate change.

Strategies on how to stop this have been the topic of political discussions, economic planning and scientific research for years. Their efficacy, however, has as yet been limited. The reason? There seems to be a Catch-22 to our climate crisis.

On average, human activities add 10 gigatonnes of carbon to the atmosphere each year. Reducing human-induced emissions has been the focus of much attention. Notable organizations, such as Project Drawdown, list effective refrigeration management when recycling or disposing of refrigerants as the top solution, with the potential to save 24 gigatonnes of carbon in future emissions. Converting to a plant-only diet on a global scale could save up to 18 gigatonnes.

But all of the proposed solutions – from electricity generation, to transport, food, education and land use – have one thing in common: primarily, they only prevent future emissions. To stop climate change, we must draw down the carbon already emitted into the atmosphere.

How do we do this? Ecologically speaking, trees are the most effective means to capture and store carbon. Until now, forest restoration has not been seriously considered as a climate change mitigation strategy because we have no quantitative information about what is possible. Without any scientific evidence, we have not been able to quantify the true contribution of forest restoration, and we don’t know whether this could capture an extra 10 or 110 gigatonnes of carbon.

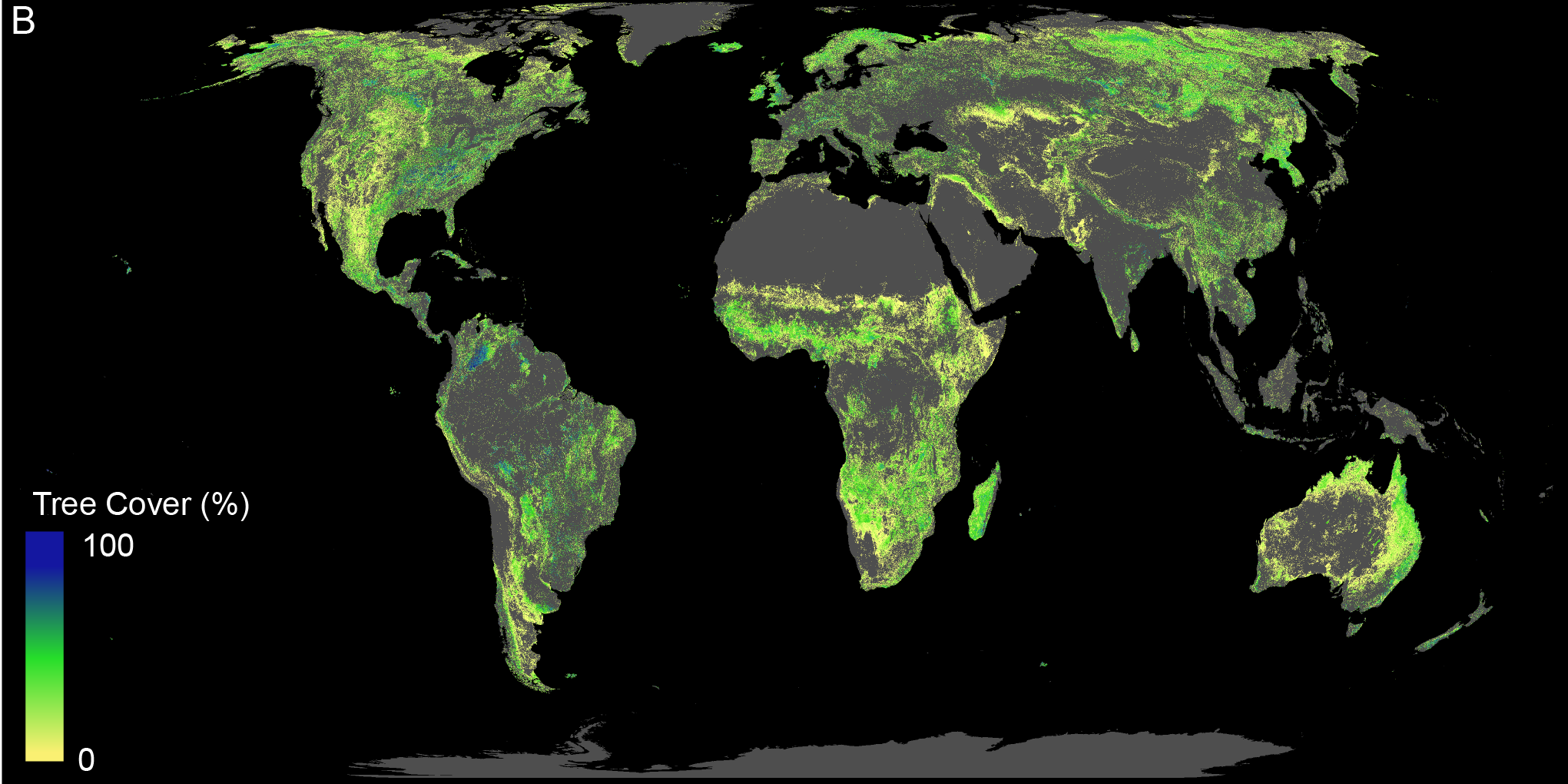

By creating a global network of ecologists with ground-sourced data from 1.2 million locations across the world and pairing this with satellite data, the Crowther Lab has used machine learning to create the first spatially explicit map of the entire global forest system.

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

Our map shows 3.04 billion trees on Earth – seven times more than previously estimated based purely on satellite imagery. More importantly, we now know that under current climate conditions the Earth could support 4.4 billion hectares of continuous tree cover – 1.6 billion more than the currently existing 2.8 billion hectares. Of the current tree cover, 0.9 billion hectares are located outside of areas currently used for human development, such as urban and agriculture land. This means that there is currently an area of the size of the US available for tree restoration.

What does this mean? Once mature, these new forests could store 205 billion tonnes of carbon: about two thirds of the 300 billion tonnes of carbon that has been released into the atmosphere as a result of human activity since the Industrial Revolution. Given this immense impact on climate change, the Crowther Lab’s data, recently published in the journal Science, not only confirms the efficacy of the age-old concept of tree restoration, but places it as the number one solution available.

We are at the start of a massive and ever-growing movement of people trying to do something about climate change. More than 1.5 million people have marched for the climate crisis in recent months. If we could harness all of this positive energy and get behind this unifying goal, restoring Earth’s ecosystems would have the immense power to restore our climate.

With our maps, we have the tools to do so, showing exactly where in the world restoration activities should be focused in order to be the most effective. Our maps allow each and every citizen to zoom in and learn more about an area, whether it can carry trees and which type of tree.

This is the power of restoration. Many governments around the globe have already pledged to restore forest systems – Australia and New Zealand, for example, each plan to plant 1 billion trees. But as a nature-based solution, citizens must not purely rely on the engagement of governments to achieve effective restoration. If we inspired and guided millions of global citizens to get together and engage in this, the impact would be tremendous.

What’s the World Economic Forum doing about deforestation?

We suggest three different, but equally simple and straightforward ways for getting involved as a citizen:

1. Restore: start planting trees – in your garden or in your local community, it’s easy to do and fun. Try to contact local authorities, scientists or NGOs which can give you extra information about local species that could be suitable for restoration. The maps on the Crowther Lab website support you in finding the best locations for restoring trees.

2. Support: many organizations and NGOs around the world are actively working on the restoration of vegetation and soils.

3. Be a smart consumer: as consumers we can make conscious decisions that can favour the protection of the planet. By supporting companies and activities that aim for a sustainable planet, buyer power can go a long way in the fight against climate change.

For consistency, in this article we have converted all CO2 figures to carbon. 44 grams of CO2 has approximately 12 grams of carbon.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Nature and BiodiversitySee all

Tom Crowfoot

July 8, 2025

Michael Donatti and Laura Fisher

July 3, 2025

Tim Lenton and Steve Smith

June 30, 2025

Susan Hu and Zhang Yuan

June 27, 2025

Allison Voss

June 25, 2025