How Big Food is responding to the alternative protein boom

Plant-based foods are leading growth for the food sector

Image: REUTERS/Andres Stapff

Stay up to date:

Agriculture, Food and Beverage

On average, humans slaughter over 70 billion animals for food every year. That’s 130,000 animals every minute.

This scale is only possible because we’ve transformed animal agriculture from a predominantly pastoral, family-owned farming system to an industrialized system of livestock production. It’s one that has created a $1.5 trillion industry, serving as the backbone for the rise of Big Food and inspiring iconic products, from the Big Mac to the Whopper. It has made animal proteins – whether from milk, meat or fish – so ubiquitous that the price of a Big Mac provides a standard to gauge currency misalignment between countries, and chicken bones may serve as an index fossil that defines the Anthropocene.

But increasingly, it’s a system that is under scrutiny for the scale of its impact on people and the planet. These concerns are driving consumers to seek substitutes for the meat and dairy they love and inspiring innovators to meet this market demand through disruption: replicating the taste, texture and flavour of animal proteins with better resource efficiency and without the actual animal.

These developments have challenged the long-held thesis that the only way for the sector to grow (and feed a world of 10 billion people by 2050) is through the expansion of our current intensive animal production system. For the first time since the advent of industrial animal agriculture nearly 60 years ago, alternative proteins – whether plant-based or cell-based – present a viable path forward to meet global demand for proteins sustainably.

Since 2016, FAIRR – a network of over 250 institutional investors – has coordinated the world’s only collaborative investor engagement with 25 global, listed food companies. Our engagement encourages food giants to adopt a strategic approach to diversifying protein sources away from an over-dependence on animal proteins – both to leverage market opportunity and to de-risk supply chains.

Here are six essential takeaways from FAIRR’s new report, Appetite for Disruption, on how Big Food is responding to the alternative protein boom:

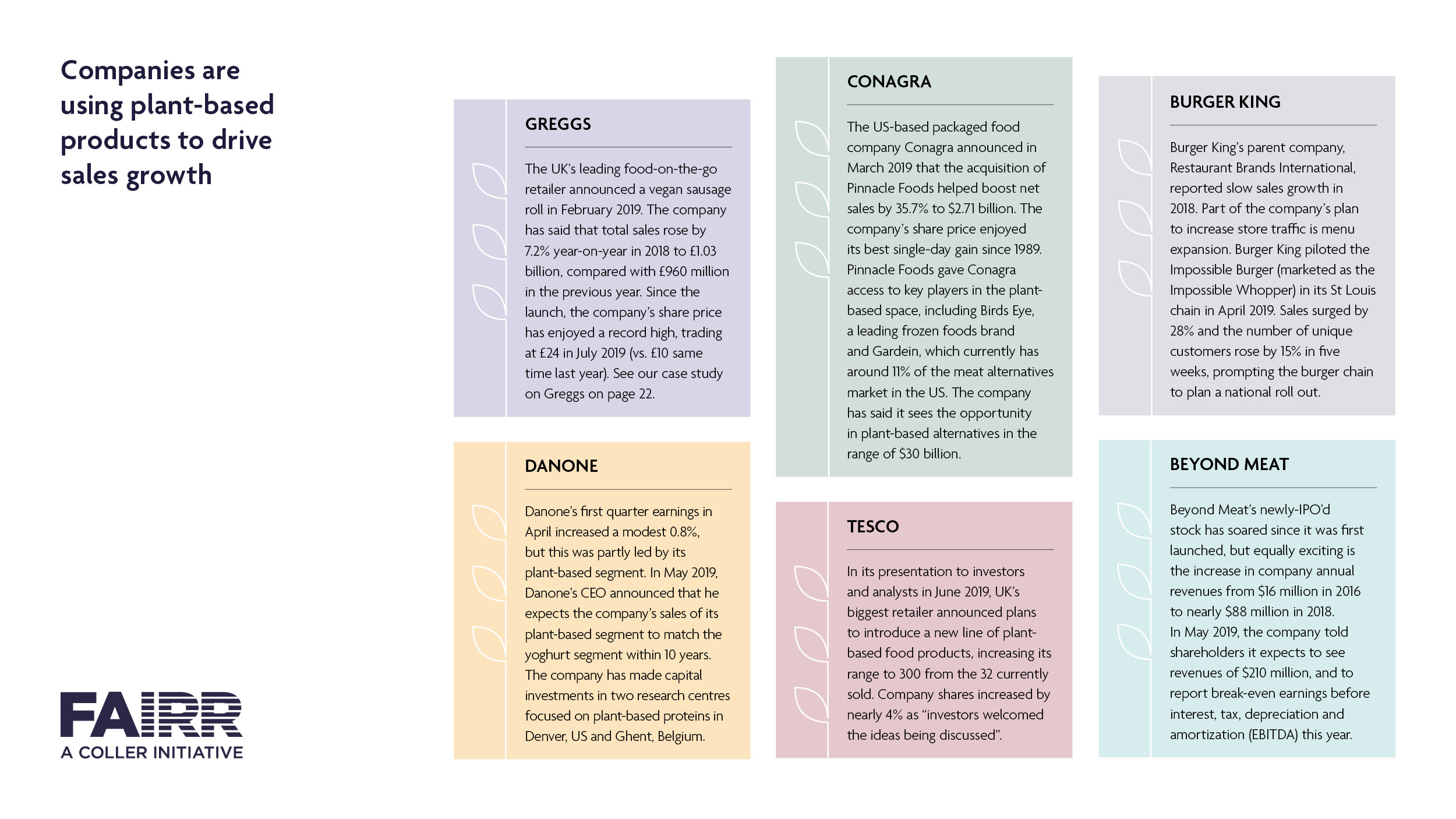

Plant-based foods are leading growth for the food sector: in the US, sales of plant-based foods have grown by 31% over the last two years vs 4% for retail food sales. It’s no wonder that terms like “plant-based” and “vegan” now regularly appear in company communications: in 2018-19, 64% of the companies in FAIRR’s engagement referred to these terms in their annual reporting and quarterly earnings calls to investors.

The rapid rise of the plant-based market has producers, retailers and food brands playing catch-up. New entrants like Beyond Meat, Just and Impossible Foods have forced established players to innovate, invest and launch new products to avoid a disruption of their existing brands.

Just this year, analysts from JP Morgan, Barclays, AT Kearney and UBS have weighed in on how quickly alternative meat will capture market share from traditional meat. Milk alternatives have already grabbed market share and now account for 13% of US retail milk sales.

No company has yet successfully demonstrated measurable reduction on risks associated with animal protein supply chains. Many have not even begun the journey: only 28% of companies in FAIRR’s engagement have set targets to reduce supply chain emissions. Despite years of working to curb deforestation from soy (predominantly used for animal feed) and cattle-ranching, most food companies will not be able to meet their target to halt deforestation by 2020.

This drives home a clear message: a sole focus on supply chains to tackle risks will require increased capital investment with limited benefits as demand for meat, dairy and fish grows. These initiatives will have to be balanced against growing consumer demand for better welfare, lower antibiotics use, slower-growing breeds, no confinement and no routine mutilation, all of which will result in higher costs. This will ultimately put pressure on an industry where net margins are small to begin with, averaging around 2-3%.

On the other hand, reducing exposure to resource-intensive commodities can have immediate benefits – in 2019, General Mills decreased emissions from agriculture by 17% versus its 2010 baseline, primarily due to reduced purchases of dairy.

Our analysis identified that all 16 retailers have expanded their alternative protein product portfolios in the last year.

For retailers, private-label ranges present an important opportunity to expand their selection of affordable alternative protein options. In the US, for example, sales of private-label brands grew at 4.3%, vs. 1.2% for external brands. Within our engagement, over 87% of retailers, apart from Costco and Walmart, have ramped up their private label alternative protein products across categories to compete with external brands.

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

On the manufacturing side, companies are expanding their exposure to alternative proteins primarily through acquisitions, venture investments and new product launches. Making early-stage minority investments into start-ups is a popular approach. It gives corporates access to innovation across a broad range of technologies and to evolving consumer trends, as an alternative to making a larger commitment to strategic acquisition (the more traditional M&A route). Eight of the nine manufacturers in our engagement now demonstrate a combination of all three approaches.

Overall, regulatory activity is favourable to the sector: both the EU and the US have updated their regulatory processes to cover novel ingredients and cell-cultured products, reducing the barriers to market entry for alternative proteins. In the US, the pathway to regulate cell-cultured meat was especially contentious after an intense inter-agency dispute on who should regulate the industry. In 2018, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the FDA agreed to a joint regulatory framework. However, regulation is also being used as the new battleground by the traditional (and powerful) animal protein lobbies to push back on the alternative protein sector’s explosive growth. In the US, 24 states have passed legislation barring the use of words like “steak”, “burger” and “milk” for plant-based foods.

In response, the alternative proteins industry is organizing to protect and advocate for its interests. Organizations like Plant Based Foods Association and the Good Food Institute in the US and the European Plant-Based Foods Association in Europe are working to advance the policy interest of the sector. Big Food is now entering the space: both Kellogg’s and Campbell Soup are now part of the Plant-Based Foods Association. Many alternative protein start-ups are also working with longstanding food industry veterans to help them navigate regulatory complexities and build and scale their go-to-market strategies.

Our methodology measures how prepared Big Food is when it comes to leveraging alternative proteins for growth and risk mitigation. We assessed 25 companies on their recognition of risks linked to their animal protein supply chains (materiality); their work to tackle risks through commitments (strategy); how they are expanding alternative protein portfolios (product expansion & consumer engagement); and finally, whether companies are measuring their progress (tracking & reporting).

Our findings indicate that Unilever demonstrates the most proactive approach to protein diversification. The company recognizes the materiality of the issue for its business, is working to mitigate these risks through its supply chain interventions and science-based climate target, and has been expanding its access to alternative proteins through acquisitions, product development and clever consumer engagement.

On the other hand, we found Costco’s approach to be the most reactive. Despite being one of the largest sellers of chicken and beef in the US, Costco has limited discussion of impacts of these supply chains, and is increasing its exposure to these commodities. While the company has expanded its range of plant-based external brands, we found limited innovation in its signature private-label brand, Kirkland.

For companies and investors, an expanding alternative protein portfolio is a clear lever for growth. More importantly, it is a fundamental and necessary component to manage a company’s environmental and social risks while improving its ability to compete and innovate.

As FAIRR’s founder, Jeremy Coller, has said: “A fourth agricultural revolution is underway in the world of protein production.” The billion-dollar question is, will Big Food keep pace?

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Industries in DepthSee all

Francisco Betti

May 9, 2025

David Elliott and Johnny Wood

April 25, 2025

Katia Moskvitch

April 14, 2025

Cathy Li and Andrew Caruana Galizia

March 3, 2025

Francesco Venturini and Bart Valkhof

February 27, 2025