Water pollution is killing millions of Indians. Here's how technology and reliable data can change that

It's estimated that around 70% of surface water in India is unfit for consumption

Image: REUTERS/Babu

Stay up to date:

SDG 06: Clean Water and Sanitation

Humans have wrestled with water quality for thousands of years, as far back as the 4th and 5th centuries BC when Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine, linked impure water to disease and invented one of the earliest water filters. Today, the challenge is sizeable, creating existential threats to biodiversity and multiple human communities, as well as threatening economic progress and sustainability of human lives.

As India grows and urbanizes, its water bodies are getting toxic. It's estimated that around 70% of surface water in India is unfit for consumption. Every day, almost 40 million litres of wastewater enters rivers and other water bodies with only a tiny fraction adequately treated. A recent World Bank report suggests that such a release of pollution upstream lowers economic growth in downstream areas, reducing GDP growth in these regions by up to a third. To make it worse, in middle-income countries like India where water pollution is a bigger problem, the impact increases to a loss of almost half of GDP growth. Another study estimates that being downstream of polluted stretches in India is associated with a 9% reduction in agricultural revenues and a 16% drop in downstream agricultural yields.

The cost of environmental degradation in India is estimated to be INR 3.75 trillion ($80 billion) a year. The health costs relating to water pollution are alone estimated at about INR 470-610 billion ($6.7-8.7 billion per year) – most associated with diarrheal mortality and morbidity of children under five and other population morbidities. Apart from the economic cost, lack of water, sanitation and hygiene results in the loss of 400,000 lives per year in India. Globally, 1.5 million children under five die and 200 million days of work are lost each year as a result of water-related diseases.

To set up effective interventions to clean rivers, decision-makers must be provided with reliable, representative and comprehensive data collected at high frequency in a disaggregated manner. The traditional approach to water quality monitoring is slow, tedious, expensive and prone to human error; it only allows for the testing of a limited number of samples owing to a lack of infrastructure and resources. Data is often only available in tabular formats with little or no metadata to support it. As such, data quality and integrity are low.

Using automated, geotagged, time-stamped, real-time sensors to gather data in a non-stationary manner, researchers in our team at the Tata Centre for Development at UChicago have been able to pinpoint pollution hotspots in rivers and identify the spread of pollution locally. Such high-resolution mapping of river water quality over space and time is gaining traction as a tool to support regulatory compliance decision-making, as an early warning indicator for ecological degradation, and as a reliable system to assess the efficacy of sanitation interventions. Creating data visualizations to ease understanding and making data available through an open-access digital platform has built trust among all stakeholders.

Beyond collecting and representing data in easy formats, there is a possibility to use machine learning models on such high-resolution data to predict water quality. There are no real-time sensors available for certain crucial parameters estimating the organic content in the water, such as biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), and it can take up to five days to get results for these in a laboratory. These parameters can potentially be predicted in real-time from others whose values are available instantaneously. Once fully developed and validated, such machine learning models could predict values for intermediary values in time and space.

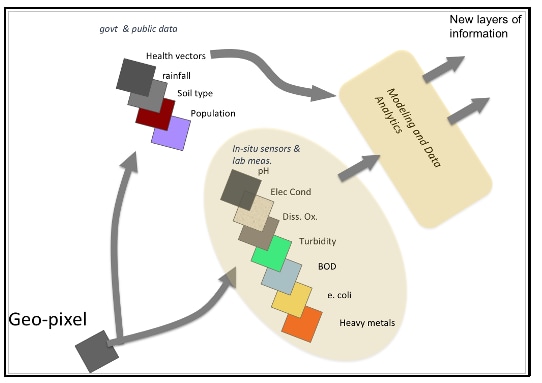

Furthermore, adding other layers of data, such as the rainfall pattern, local temperatures, industries situated nearby and agricultural land details, could enrich the statistical analysis of the dataset. The new, imaginary geopixel, as Professor Supratik Guha from the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering calls it, has vertical layers of information for each GPS (global positioning system) location. Together they can provide a holistic picture of water quality in that location and changing trends.

In broad terms, machine learning can help policy-makers with estimation and prediction problems. Traditionally, water pollution measurement has always been about estimation – through sample collection and lab tests. With our technology, we are increasing the scope and frequency of such estimation enormously – but we are also going further. With our machine learning models, we are trying to build predictive models that would completely change the scenario of water pollution data. Moreover, our expanded estimation and prediction machine learning tools will not just deliver new data and methods but may allow us to focus on new questions and policy problems. At a macro level, we aim to go beyond this project and hope to bring a culture of machine learning into Indian Public Policy.

What is the World Economic Forum's India Economic Summit 2019?

Access to information has been an important part of the environmental debate since the beginning of the climate change movement. The notion that “information increases the effectiveness of participation” has been widely accepted in economics and other social science literature. While the availability of reliable data is the most important step towards efficient regulation, making the process transparent and disclosing data to the public brings many additional advantages. Such disclosure creates competition among industries on environmental performance. It can also lead to public pressure from civil society groups, as well as the general public, investors and peer industrial plants, and nudge polluters towards better behaviour.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Geographies in DepthSee all

Aimée Dushime

April 18, 2025

Samir Saran and Anirban Sarma

April 17, 2025

Nada AlSaeed

April 16, 2025

Zhang Xun and Vee Li

April 8, 2025

Abdulwahed AlJanahi

March 3, 2025

Naoko Tochibayashi and Mizuho Ota

February 28, 2025