The ocean is teeming with microplastic – a million times more than we thought, suggests new research

There might be 8.3 million pieces of microplastics per cubic metre of water in our oceans. Image: REUTERS/Thierry Gouegnon

- New research suggests the scale of plastic pollution in our oceans could be a million times worse than previously recorded.

- The researchers analysed the intestines of tiny filter-feeding invertebrates called salps, finding previously undetected mini-microplastics.

- Although ocean plastics break down over time, microscopic remnants remain in the water and could enter the food chain.

There could be a million times more microplastics floating around our oceans than previously thought, according to new research suggesting existing studies could have seriously underestimated the problem.

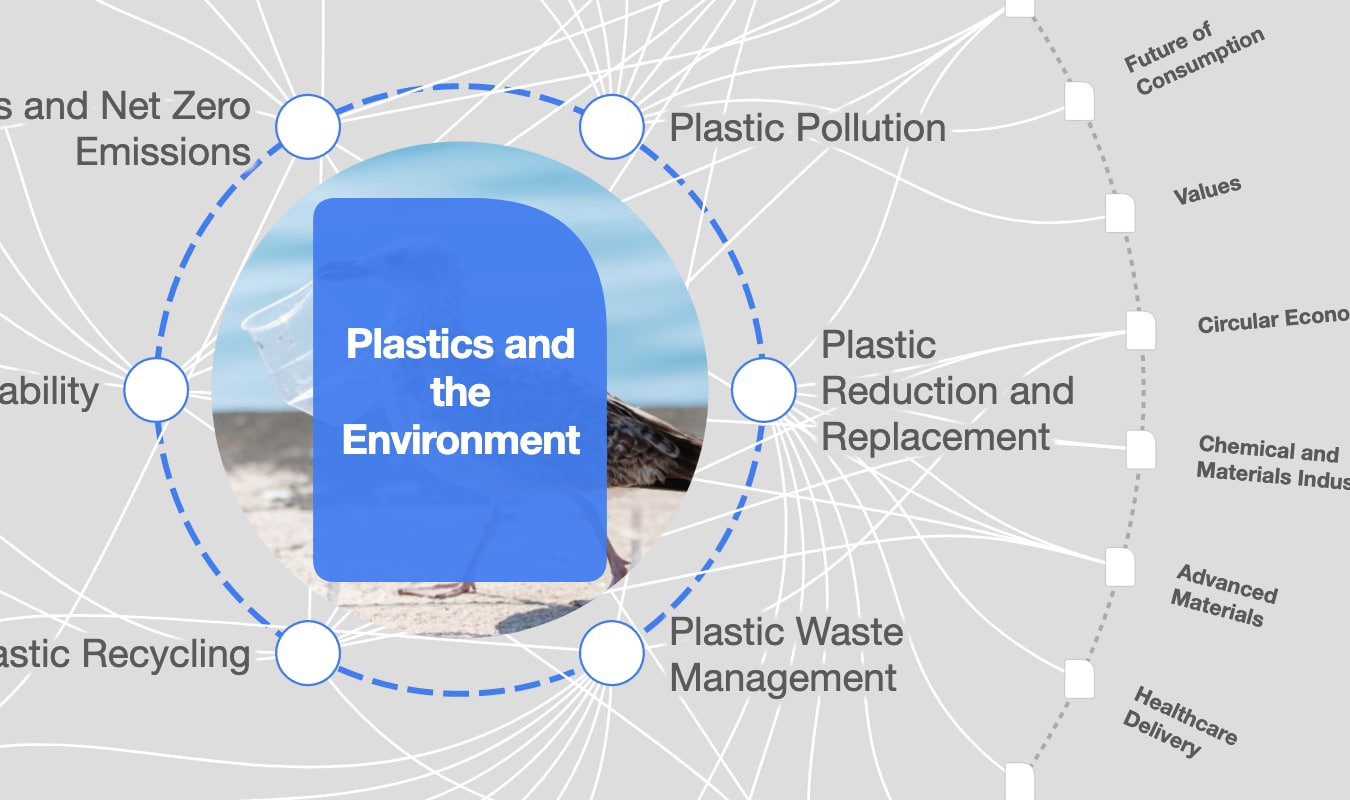

How UpLink is helping to find innovations to solve challenges like this

Some microplastics – defined as fragments measuring less than 5 mm – are too small to be caught in the nets traditionally used to collect samples, making them go unnoticed. But researchers say a new technique has enabled more accurate measurements, capturing pieces smaller than the width of a human hair.

The study, led by biological oceanographer Jennifer Brandon of Scripps Institution of Oceanography, published in the science journal Limnology and Oceanography Letters, found the concentration of tiny plastic pieces could be five to seven orders of magnitude greater than previously thought.

These fragments make their way into the world’s waterways and end up in our oceans.

More than one-third of microplastics in the ocean come from synthetic fabrics, such as polyester or nylon. Car tyres are the second-leading source, releasing plastic particles as they erode.

Record plastics

To more accurately record the level of microplastic pollution in ocean waters, the researchers analysed seawater salps, which are tiny, barrel-shaped filter feeders. These invertebrates inhabit ocean waters to depths of around 2 kilometres.

Salps pump salt water through their bodies as they perform a pulsing movement both to feed and to move through the ocean. Filter-feeding in the ocean depths makes them a likely place to find microplastics, the researchers say.

All of the salp samples taken from three different ocean zones had mini-microplastic particles in their stomachs. Since food passes through the creature’s digestive system in two to seven hours, it was an alarming find.

“The thing that truly surprised me the most was that every salp, regardless of year collected, species, life stage, or part of the ocean collected, had plastic in its stomach,” Brandon explained to Earther. “A species having 100% ingestion rates is quite extraordinary, and devastating for the food web that eats salps.”

What's the World Economic Forum doing about the ocean?

Food for thought

The findings overtake previous estimates of 10 microplastic fragments per cubic metre of ocean water. When the abundance of mini-microplastics is included, the recalibrated figure is closer to 8.3 million pieces per cubic metre.

Although ocean plastics break down over time, microscopic remnants remain in the water.

Larger fish and other marine species feed on creatures like salps, potentially allowing microplastics to enter the food chain, the researchers say, working their way up to contaminate humans' food.

According to the UN Environment Programme, 13 million tonnes of plastic leak into our oceans every year, causing an estimated $13 billion of economic damage to global marine ecosystems.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Plastic Pollution

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.