Plastic waste from Western countries is poisoning Indonesia

Plastic is burned on a large scale to ease Indonesia’s overflowing rubbish dumps. Image: REUTERS

- Indonesia has become a dumping ground for plastic from Australia, Europe and North America.

- The waste is burned as fuel by local communities, causing respiratory illness and other long-term health problems for people who inhale the polluted smoke.

- Research shows pollutants have contaminated Indonesia's food chain.

Every day, people in Western countries in Australia, Europe and North America diligently separate their household plastic waste to be collected and sent for recycling. But much of it isn’t recycled. Instead it is exported – sometimes illegally – to Indonesia and neighbouring countries, polluting the air and affecting the health of local people.

The waste arrives by container, sometimes as a legitimate import, sometimes concealed in other shipments. And it's compounding a domestic plastics problem that generates 9 million tonnes of waste annually.

Plastic is burned on a large scale to ease Indonesia’s overflowing rubbish dumps, while truckloads of waste are sold to local communities.

Local people cherry-pick the best bits to sell to local plastics factories. The leftover piles of poor-quality waste provide a cheap and plentiful fuel source for local businesses.

But there's a hidden cost: the incinerated plastic causes respiratory problems for people who inhale its toxic smoke.

Poisonous plastics

Indonesia has become a dumping ground for vast quantities of the world’s unwanted plastic since China banned imports of foreign plastic waste. In 2018, imports of plastic waste to the Southeast Asian nation doubled over the previous year, to 320,000 tonnes.

Researchers at the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN) found harmful chemicals contained in the plastic have contaminated the local food chain, exposing people to toxins linked to serious health problems, such as cancer, diabetes and immune system damage.

In the East Java village of Tropodo, a cluster of tofu factories generates plumes of black smoke from burning plastic fuel. An analysis of local egg samples showed they contained extremely high levels of harmful persistent organic pollutants (POPs). Levels of dioxins were similar to the highest ever recorded in Asia – 70 times higher than the European Food Safety Authority’s (EFSA) recommended safe daily intake.

A persistent problem

Indonesia is barely able to cope with its own waste. The World Bank estimates that one-fifth of the country’s plastic ends up in rivers and coastal waters.

The government has sent waste shipments back, but they are often redirected elsewhere. For example, environmental groups Nexus3 and BAN found that just 12 of 58 containers returned to the United States arrived, Reuters reports. Instead, 38 arrived in India and the remaining containers were tracked to South Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, Mexico, the Netherlands and Canada.

So, the problem persists.

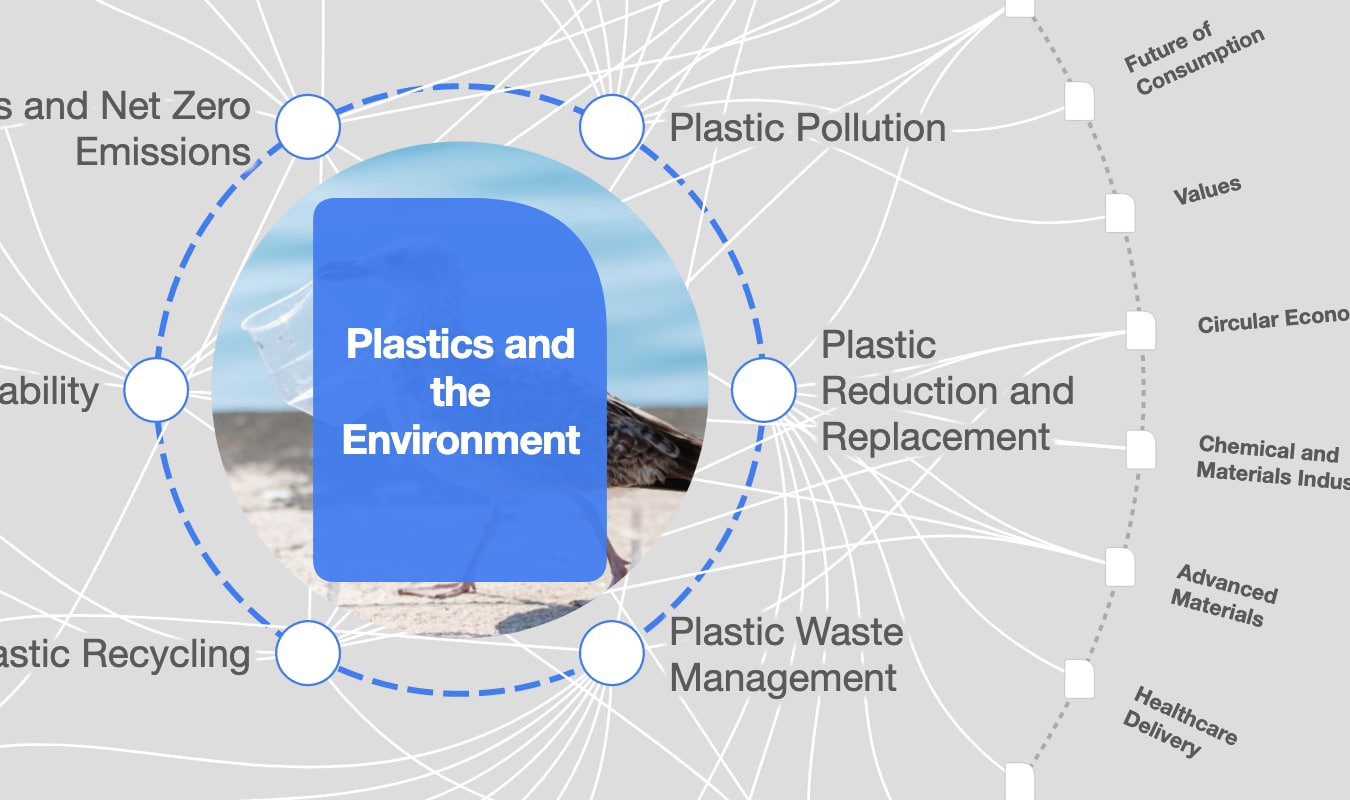

What is the World Economic Forum doing about plastic pollution?

Globally, only 9% of the 9 billion tonnes of plastic produced since 1950 has been recycled. Around 13 million tonnes of plastic waste leaks into our oceans a year, causing $13 billion of economic damage to the planet’s marine ecosystems.

If current plastic production trends continue, IPEN says, 26 billion tonnes will be produced by 2050 – four times more than the world has produced to date.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Plastic Pollution

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Nature and BiodiversitySee all

Federico Cartín Arteaga and Heather Thompson

December 20, 2024