Fighting malnutrition from the grassroots of India

A worker pulls a container carrying a free mid-day meal, distributed by a government-run primary school, for school children in New Delhi. Image: REUTERS/Ahmad Masood

- In 2012, Save the Children reported that 1.83 million Indian children die every year before they turn five and malnutrition is the key reason for the deaths.

- If India's health policies continue in the same way, the country will see no end to malnutrition.

Jharkhand has India’s sixth worst infant mortality rate. Analysis of Jharkhand’s National Family Health Survey 2015-16 shows that the health and nutritional status of children is critically low compared to the national standard: some 9 out of 10 children between the ages of 6 and 23 months do not receive an adequate diet.

The nutrition factor

In villages in Chaibasa, West Singhbhum in Jharkhand, some children are fed a local drink called hariya so that they remain intoxicated and do not have the energy to ask for food.

In Jharkhand, about 48% of children under five are underweight and 29% wasted, the highest rates in the country.

For children with acute malnourishment, few have undergone treatment in Malnourishment Treatment Centres in the last few years though Anganwadi workers send them there. According to one woman, it takes a minimum of two weeks for the mother to get admitted alongside their children into these centres. Most women cannot afford to do this anyway as they have family at home they must take care of. It is therefore important to understand whether government policies are practical or not.

The food problem

In November 2017, a ‘Gift Milk’ government initiative ended up providing milk to only 12,000 students in government schools in Latehar under a CSR scheme.

Anganwadis under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) schemes are supposed to provide hot meals for children under 3- 6 years of age in the communities. But children get very little food, with little soybean or potatoes at times. And parents do not complain about the quality of the food because the conditions at home are worse. Paani bhaat (rice and water) and a pickle made out of tomato is usually a daily diet for the majority of people in Chaibasa. Daal (pulses) and vegetables makes it to plates once a week. A lot of parents in the community whose children were underweight, wasted or stunted during the time they were in school have never even heard the word kuposhan (malnourishment) in their local language.

Half-finished supplements

Every month, children receive four packets of Take Home Ration (THR), ready-to-eat supplements which they are supposed to consume once a day. Parents fail to understand how these packets help their children’s health and most Anganwadi workers do not know what are in these supplements.

For some Anganwadi workers, these packets are just another task for them as they have to distribute them. If asked about the ingredients they will tell you, “I will give you the packet and read it yourself – we don’t know.” They have received no official training. There have been no talks about the benefits of these packets. The result is that parents have mostly stopped feeding their children these packets. They think these supplements make them more sick.

More about the Anganwadis

Since 2016, Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana, a scheme of the Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas, has been providing Liquefied Petroleum Gas to houses below the poverty line (BPL) in rural India. However, the irony is that the Anganwadis tend to cook food in traditional hearths to this day. At any given morning, burning hearths over which khichdi (a mixture of pulses and rice) is cooked emit so much smoke they make children sick.

Namita Devi (name changed), is an Anganwadi worker who received a new Anganwadi building with white walls and blue gates after 10 years of running a centre out of someone’s house. Namita admitted that she puts the names of the children as present in the register even if they do not turn up at the centre as she fears losing allotted funds, and would have to close down the centre.

Namita told us that she buys food and fuel for the centre from the local market and is asked to claim the reimbursements and apply for funds at a highly subsidised government rate. This ensures that Anganwadi workers remain in a cycle of debt all the time.

It is important to understand that while the government promotes various schemes in rural India, stakeholders struggle to implement them.

In 2012, Save the Children reported that 1.83 million Indian children die every year before they turn five and malnutrition is the key reason for the deaths. Having said that, several districts in Jharkhand continue to be denied ration as families have not been able to show their Adhaar card.

The stories mentioned in this article compel us to reflect on the accountability of government schemes at the grassroots level. It also compels us to ask that stakeholders be heard in the global decision-making process – this is a priority.

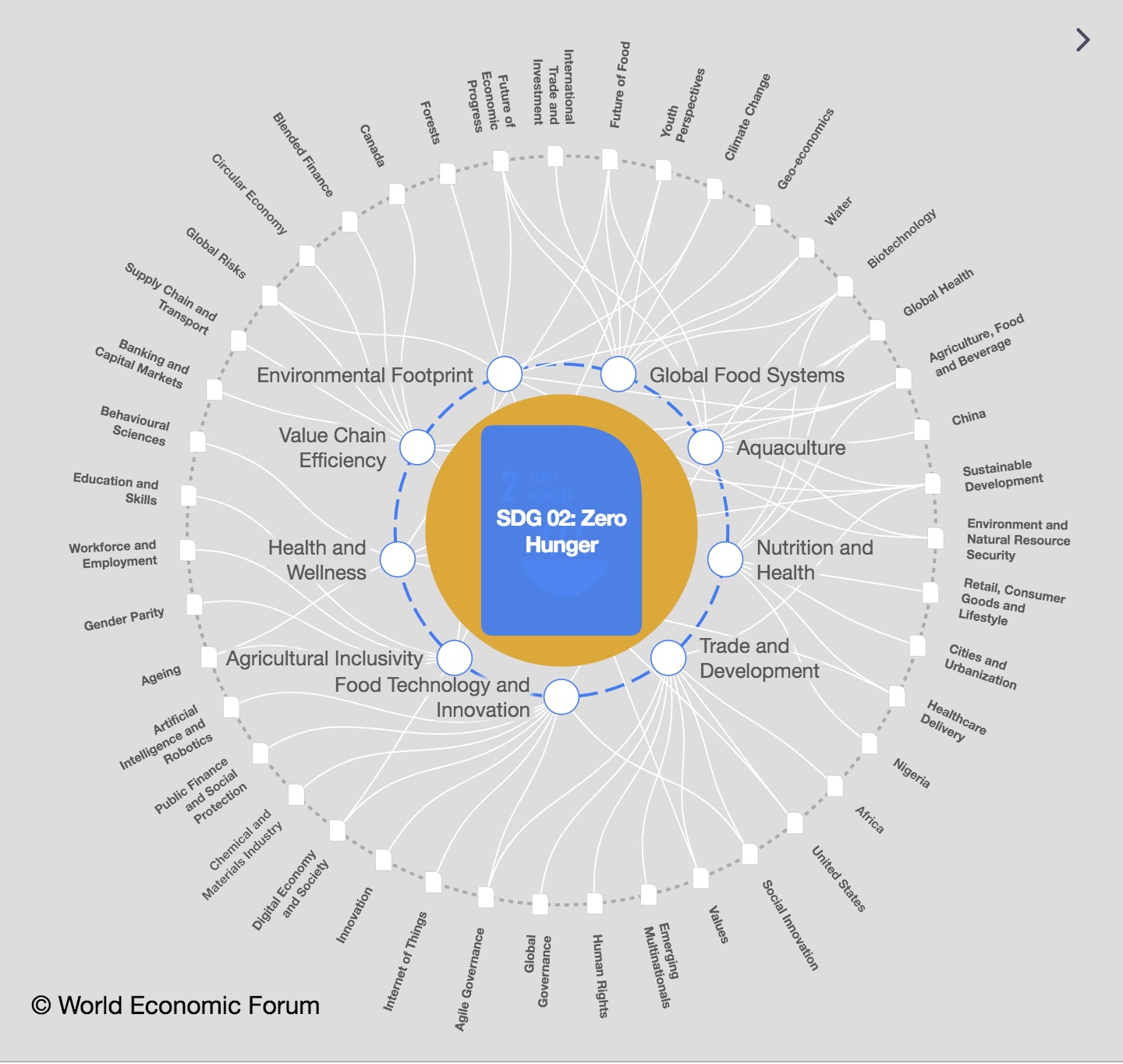

Without that, dilapidated policies and struggling communities of health and nutrition professionals are such that India will miss the second of the UN’s sustainable development goals: ending malnutrition by 2030.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

SDG 02: Zero Hunger

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Forum InstitutionalSee all

Beatrice Di Caro

December 17, 2024