It's time to change the way we think about the value of media

The growth in media companies' investment in content has far outstripped their revenue growth

Image: REUTERS/Regis Duvignau

Stay up to date:

Media, Entertainment and Information

- The worldwide value of new media content each year plausibly runs to hundreds of billions of dollars.

- Growth in this spending has far outpaced growth in companies' revenues – a seemingly contradictory and unsustainable state of affairs.

- A new report from the World Economic Forum and Accenture presents a framework with which to understand the transformation of this sector.

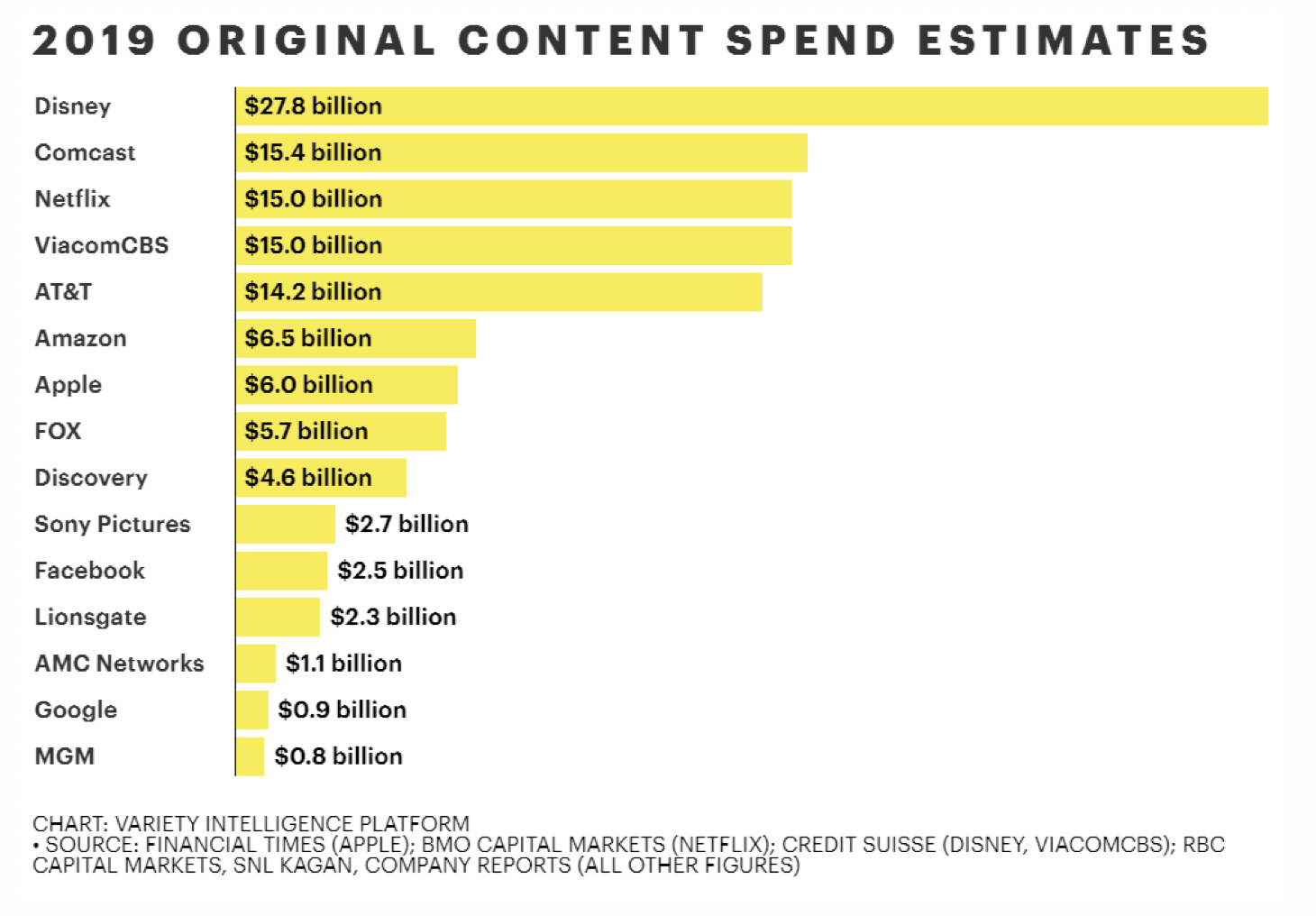

In 2019, media and entertainment companies spent more than $120 billion on original content. Astonishingly, this amount is not even fully representative of total global expenditure on content. Aside from focusing only on American companies, it also excludes other costs, such as licensing, which for the most popular shows can be worth upwards of $100 million per year, or the price of sports rights. Taking these into account, it’s quite plausible that the worldwide value of content easily stretches into the hundreds of billions of dollars every year.

Indeed, it is by now commonplace to see charts – like the one below – highlighting the seemingly bottomless budgets at the world’s biggest media and technology companies. Such data is presented as evidence of the intensity of competition in the so-called streaming wars, a supposedly winner-takes-all battle between different providers over content and attention.

While investment in content has grown substantially, it has far outpaced growth in revenue from TV advertising, movie ticket sales and over-the-top video subscriptions. If direct monetization is so difficult, why do many media companies keep investing in new content? To understand this seeming contradiction, a new framework for understanding the value of media is needed.

This is because, although the absolute values are relevant, concentrating on them exclusively ends up masking the complete reality of how the industry is changing. If the premise is that investment is the primary driver of success, one could simply argue that spending more is the logical next step for any media company seeking to gain market share.

By this metric, certain companies would have more room to grow than others. At Netflix, for example, which regularly appears on lists of who spends the most on content, almost three quarters (74%) of the company’s revenue is allocated to original content. This is likely pushing close to the limit of what is possible financially. Lionsgate, which invests almost two-thirds of its revenue on content, is in a similar position.

Amazon and Apple, on the other hand, might appear to have smaller content budgets ($6-$7 billion each), even though they still place in the global top-10 buyers of content. And while both are frequently cited as new and aggressive entrants in the entertainment market, these amounts represent only around 2% of revenue at either company.

There is certainly headroom for greater investment; if their objective was to ‘win’ the streaming war, they could comfortably top other providers and still keep spend below 7% of revenue. Doing so would bring them in line with AT&T, which, as owner of WarnerMedia, spends around 8% of its income on original content.

Yet unfortunately, none of this can tell us whether spending more leads to content that is objectively better, nor whether it makes consumers more likely to pay for it. Rather, a more nuanced look is required: one that explains how and why the monetization model for media is changing, and how content is increasingly used as a vehicle for companies to find new and better ways to connect with consumers.

As early as 2015, for example, Amazon highlighted the value of Prime Video to its overall Prime offering. According to Jeff Bezos’ letter to shareholders that year, people who watch Prime Video are more likely to both convert from a free to a paid membership, as well as renew their Prime subscription. A standalone Prime Video subscription costs about 30% more than an annual Prime membership; for this reason, Amazon effectively gives away Prime Video to direct consumers towards Prime instead, which then drives sales to other Amazon properties.

For AT&T, the expected subscription revenue from HBOMax is not likely to add much to its $181 billion annual revenues. But according to one analyst, including the service in its mobile package helps acquire and retain customers, where a decrease of just 0.1% in wireless churn is equivalent to $350m in cash profit.

Ultimately, it’s clear that the value of media to many of the biggest businesses is in its ability to underpin, reinforce and grow other parts of their companies. This is one reason behind the shrinking life span of TV series on streaming services: these providers just need to do enough to attract and retain subscribers; locking them in to their ecosystems is the bigger strategic goal.

With this in mind, there needs to be a more sophisticated way of examining the complex web of relationships in the media industry today, one that goes beyond headline figures on spend or subscriber count. One attempt to do so is demonstrated in this new report from the World Economic Forum and Accenture. Here, we have developed a ‘value map’ that provides an alternative framework for considering how the future of the industry will develop.

In doing so, the report highlights the following six implications for the media and entertainment industry (see below). These include consolidation around direct-to-consumer platforms, the growing tension between profitability and distribution, and the power of first-party data in placing media companies at an advantage.

To create a viable future for media, stakeholders in the industry will need to adjust their strategies in light of these trends and let go of old constructs which no longer serve consumers and society at large.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Industries in DepthSee all

Katia Moskvitch

April 14, 2025

Cathy Li and Andrew Caruana Galizia

March 3, 2025

Francesco Venturini and Bart Valkhof

February 27, 2025

Joe Myers and Madeleine North

February 19, 2025

Minos Bantourakis and Francesco Venturini

January 21, 2025