5 lessons for community-focused planning during a pandemic

Pre-COVID face-to-face community planning in Khorog, Tajikistan.

Image: Kira Intrator.

Stay up to date:

Civic Participation

Listen to the article

- The pandemic provides an opportunity to rethink how best to engage communities in urban planning.

- Remote tools have become essential – but can't replace face-to-face interaction.

- Accurate data is the foundation of effective participatory planning.

While the COVID-19 outbreak has brought about mass lockdowns and social distancing, urban planners and designers have continued work to support vulnerable communities around the world. Apart from the vital need to ensure the health and security of communities, the pandemic has provided a moment to reassess the planning, development and organization of the cities we inhabit, and for designers to reconsider tools and techniques aimed at supporting communities in need.

So how have designers continued to engage with communities? How have they improved their participatory planning tools? And what potential discoveries have been made?

The Aga Khan Agency for Habitat (AKAH), an agency of the Aga Khan Development Network, has created a bespoke urban and rural planning framework and participatory planning methods (known as “Habitat Planning”) at the village level and peri-urban planning scale in Tajikistan and Afghanistan, and will be shortly launching similar projects across Pakistan, Syria and India.

We are exploring innovative ways to continue to engage the communities they serve to ensure a participatory planning process. Based on insights from leading urban planning practitioners who have remained active throughout the pandemic, here are five key themes on how to ensure successful local engagement:

1. Use established tools when going remote

Like most businesses continuing with work while ensuring safe, infection-free conditions, development practitioners went online to communicate and run workshops. Though “there is no substitute for face-to-face interaction”, said Rahul Srivastava, Co-founder of Urbz, discussing his work in Dharavi, India, there have been great successes running participatory workshops remotely.

After the first weeks of remote working proved that internal and external communications were still operating, each of the organizations we spoke to has been energized by the possibility of all the digital platforms available. They tested online survey forms, social media outlets, video conferencing programmes, smartphone to GIS mapping tools and more.

However, because there was some resistance from adoption by the communities, they discovered the most effective engagement tools were the ones they were already using. “We have found that existing platforms are the only way that people communicate because nobody wants to download a new app on their phone just to talk to us. If it doesn't already exist, it's not going to happen,” said Jacqueline Cuyler, Director of South Africa’s 1to1 Agency of Engagement.

While it was proven that social messaging app groups were the best way of communicating, organizing and maintaining critical engagement with residents, the following questions arose: Who has access to smartphones and data in these vulnerable communities? Are you reaching a broad audience?

Where non-profit organization Kounkuey Design Initiative (KDI) had, since 2017, been conducting one-on-one surveys with 1,000+ people in the informal settlement of Kibera, Nairobi, they moved to phone surveys in the first half of 2020 due to COVID. “We provided training and equipment (including smartphones) to our Kibera-based enumerators so they could transition from face-to-face to phone surveys. And, since we already had a relationship with the panel respondents we had been surveying, it was a smooth transition. By the end of 2020, we had successfully run three waves of surveys using our toolkit,” said KDI’s Research Director Vera Bukachi.

2. Low-tech, safe solutions

While much of the work has gone online, each of the organizations we spoke with has continued to run face-to-face community workshops while employing necessary adjustments to ensure the safety of their participants. 1to1 summarized their lessons learnt when implementing community workshops safely:

Follow the latest WHO guidelines and provide the necessary equipment (e.g. face masks, hand sanitizer, handwashing facilities etc.

Ensure social distancing by having no contact greetings, reducing numbers of participants, and gathering outside and in well-ventilated spaces only.

Remind participants of good practice COVID safety though posters and noticeboards.

Use wipeable surfaces and laminate everything (e.g. use clear tablecloths over drawings, or print drawings on vinyl for people to draw on, then sanitize).

3. Smaller can mean better

Reduced numbers have been a major challenge for each organization, whether this is splitting groups to less than 10 participants, or having representative delegates from community groups. Reduced numbers mean more workshops, more staff, more time running and collating the results – and therefore more funding. “We have been very open with our donors about the fact that this is going to take longer than we intended because longer time means more money,” said Vera Bukachi.

Explaining how this has impacted the quality of resident participation, Jacqueline Cuyler said that though the numbers are reduced, the ability of each participant to contribute constructively has increased: “The information and participation are much richer due to a lot more voices being clearly heard. Those loud voices in the room aren't drowning out the rest because we're in groups of only five or 10 instead of that one voice speaking over all 50. The other contributors now have the opportunity for air time and have their own space to present an approach, a design, or a proposal.”

4. Knowledge-sharing is essential to citizen safety

Rapid collection of accurate data is one of the key aims of participatory planning - and all the more important during a crisis where knowledge-sharing is vital to supporting the group response required.

When working with vulnerable communities, development practitioners are best placed to access this data and use it to raise awareness of activities or problems and challenge COVID responses.

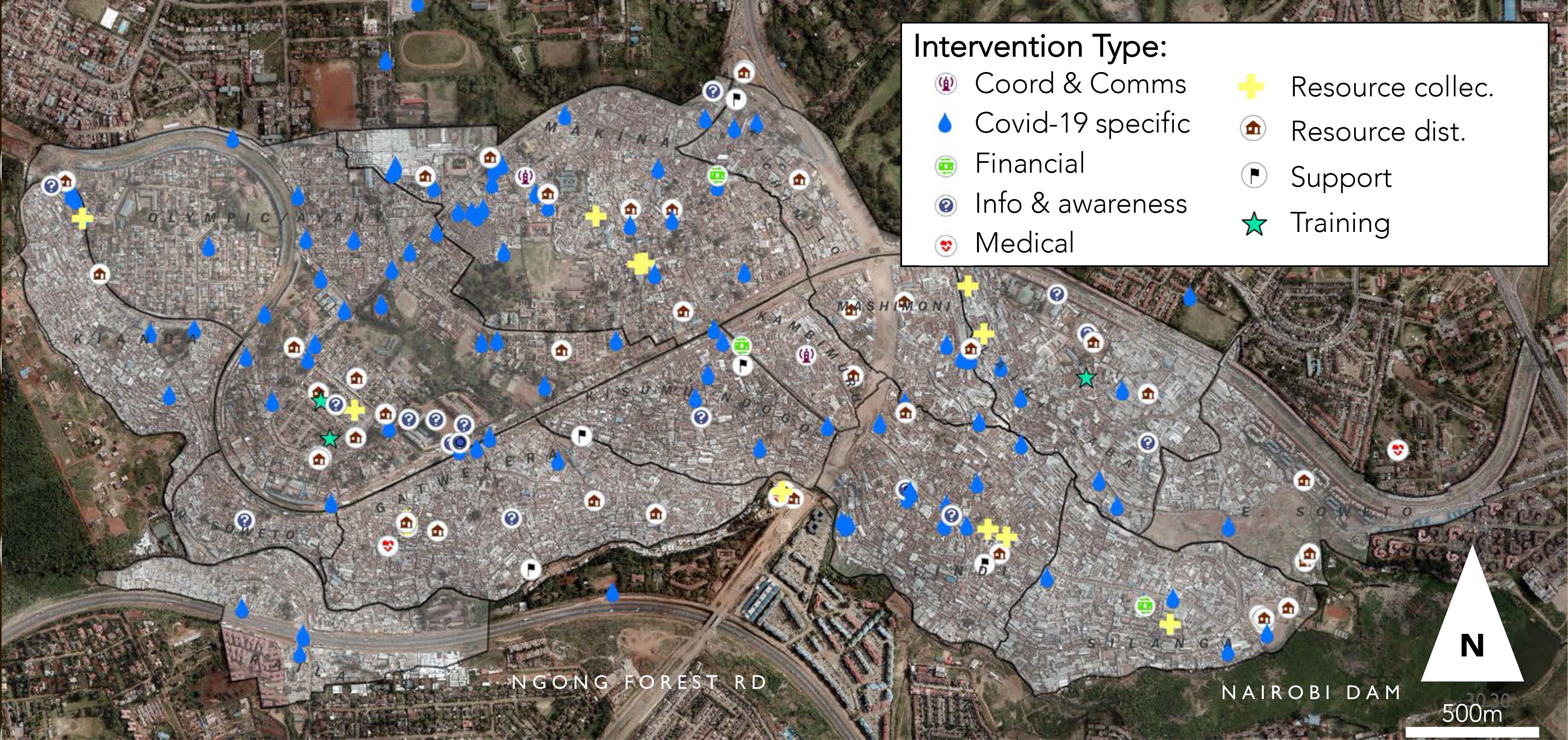

KDI worked with King’s College London to map activities in Kibera during the pandemic. “It's everything from providing water to educational materials, because schools were closed, and from providing clothing to sanitary materials for women who can't afford them, all projects established just as a result of COVID,” said Vera Bukachi.

Among KDI’s many discoveries was that it was a nine-minute round trip to/from dedicated handwashing stations for 80% of residents, longer for the other 20%. To combat this and the other problems discussed above, over 270 interventions were recorded, with 105 of these locally led. Accurate data promoted a shift away from seeing informal settlements as “hotspots” of disease and more as leading the fight for solutions.

Similarly, 1to1 has been mapping handwashing and toilet facilities in informal settlements in Johannesburg in order to advocate for more support and question whether lockdown rules apply to the same degree here. “How can you expect anyone to stay at home when their toilet is not even in their house?” said Jacqueline Cuyler.

5. Trust is key

For these organizations to have achieved the work they have amid the pandemic, an existing presence in the community and established trust have been essential. However, they have also experienced a slowing of engagement, with residents not responding to continued digital messaging without face-to-face interactions. “We have burnt years of social capital trying to maintain relationships over social media,” said Jacqueline Cuyler

There are still clear gaps in remote working and engaging with communities while social distancing and wearing a mask is required. A large part of communication is body language, which is less easily expressed over video calls, and conflict resolution is much easier face to face. Therefore there is still a balance between online and face-to-face interactions that needs to be found. “We have realised that if we are not able to do a 100% face-to-face, we can still be effective and efficient. Going forward, provided that COVID-19 is in decline, we will go back to more physical meetings, but there will be less than we used to have because they aren’t as necessary,” said KDI’s Regina Opondo.

How is the World Economic Forum supporting the development of cities and communities globally?

These practitioners’ experiences reinforces the need for flexibility and persistence in the face of uncertain conditions. Looking at these approaches, it is clear that the pandemic has created an important opportunity to reimagine how we best engage communities and promote their agency.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Urban TransformationSee all

Sam Markey, Basmah AlBuhairan, Muhammad Al-Humayed and Anu Devi

July 8, 2025

Jeff Merritt, Charlotte Boutboul and Marc Biosca

July 2, 2025

Pepe Puchol-Salort and Nicole Cowell

June 30, 2025