What the world could look like in 2500 if we don't stop global warming

The Amazon could be left unrecognisable. Image: REUTERS/Lucas Landau

- There are many reports based on scientific research that talk about the long-term impacts of climate change.

- A new study used climate change models to work out what the planet might look like by the year 2500.

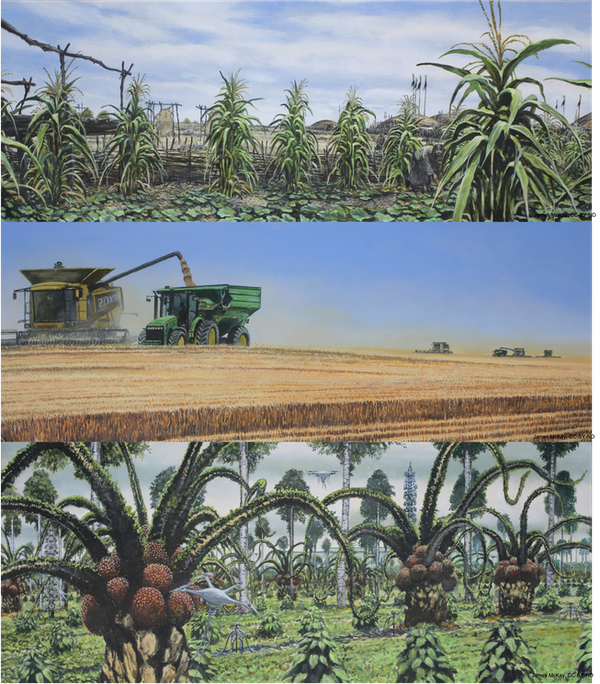

- The images show the Amazon, the Midwest United States and the Indian subcontinent at 1500, 2020, and 2500 CE.

There are many reports based on scientific research that talk about the long-term impacts of climate change — such as rising levels of greenhouse gases, temperatures and sea levels — by the year 2100. The Paris Agreement, for example, requires us to limit warming to under 2.0 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century.

Every few years since 1990, we have evaluated our progress through the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) scientific assessment reports and related special reports. IPCC reports assess existing research to show us where we are and what we need to do before 2100 to meet our goals, and what could happen if we don’t.

The recently published United Nations assessment of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) warns that current promises from governments set us up for a very dangerous 2.7 degrees Celsius warming by 2100: this means unprecedented fires, storms, droughts, floods and heat, and profound land and aquatic ecosystem change.

While some climate projections do look past 2100, these longer-term projections aren’t being factored into mainstream climate adaptation and environmental decision-making today. This is surprising because people born now will only be in their 70s by 2100. What will the world look like for their children and grandchildren?

To grasp, plan for and communicate the full spatial and temporal scope of climate impacts under any scenario, even those meeting the Paris Agreement, researchers and policymakers must look well beyond the 2100 horizon.

After 2100

In 2100, will the climate stop warming? If not, what does this mean for humans now and in the future? In our recent open-access article in Global Change Biology, we begin to answer these questions.

We ran global climate model projections based on Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP), which are “time-dependent projections of atmospheric greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations.” Our projections modelled low (RCP6.0), medium (RCP4.5) and high mitigation scenarios (RCP2.6, which corresponds to the “well-below 2 degrees Celsius” Paris Agreement goal) up to the year 2500.

We also modelled vegetation distribution, heat stress and growing conditions for our current major crop plants, to get a sense of the kind of environmental challenges today’s children and their descendants might have to adapt to from the 22nd century onward.

In our model, we found that global average temperatures keep increasing beyond 2100 under RCP4.5 and 6.0. Under those scenarios, vegetation and the best crop-growing areas move towards the poles, and the area suitable for some crops is reduced. Places with long histories of cultural and ecosystem richness, like the Amazon Basin, may become barren.

Further, we found heat stress may reach fatal levels for humans in tropical regions which are currently highly populated. Such areas might become uninhabitable. Even under high-mitigation scenarios, we found that sea level keeps rising due to expanding and mixing water in warming oceans.

Although our findings are based on one climate model, they fall within the range of projections from others, and help to reveal the potential magnitude of climate upheaval on longer time scales.

To really portray what a low-mitigation/high-heat world could look like compared to what we’ve experienced until now, we used our projections and diverse research expertise to inform a series of nine paintings covering a thousand years (1500, 2020, and 2500 CE) in three major regional landscapes (the Amazon, the Midwest United States and the Indian subcontinent). The images for the year 2500 centre on the RCP6.0 projections, and include slightly advanced but recognizable versions of today’s technologies.

What’s the World Economic Forum doing about climate change?

The Amazon

The Indian subcontinent

An alien future?

Between 1500 and today, we have witnessed colonization and the Industrial Revolution, the birth of modern states, identities and institutions, the mass combustion of fossil fuels and the associated rise in global temperatures. If we fail to halt climate warming, the next 500 years and beyond will change the Earth in ways that challenge our ability to maintain many essentials for survival — particularly in the historically and geographically rooted cultures that give us meaning and identity.

The Earth of our high-end projections is alien to humans. The choice we face is to urgently reduce emissions, while continuing to adapt to the warming we cannot escape as a result of emissions up to now, or begin to consider life on an Earth very different to this one.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Climate Crisis

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Climate ActionSee all

Johan Rockström and Tania Strauss

November 19, 2024