An economy that works for workers - watch Episode 2 of the Stakeholder Capitalism video podcast series

- Stakeholder Capitalism is a series of videos and podcasts that looks at how economies can be transformed to serve people and the planet.

- In this second episode, we look at the evolution of trade unions over past decades - and how, despite the protections they afford to both workers and wages, they're on the wane.

- Featuring insights from Washington Post economics correspondent Heather Long, and the chief economist of the Danish metalworkers union, Thomas Soby.

For many an employee on the middle of the income ladder, capitalism must feel like a rigid and rigged system. They see wages driven down in the name of profit, colleagues failing to fulfil their potential. But the jobs market is changing fast.

Two years of COVID-19 disruption have brought workers and employers alike to a point of reflection on meaningful work and how (and where) we carry it out. And as the world undergoes huge technological transformation, it's workers who want to be at the heart of the decision-making.

In this episode we ask how can we make an economy that works for those vital stakeholders, the workers.

Workers and trade unions: full transcript

Natalie Pierce: Welcome to Stakeholder Capitalism, a show from the World Economic Forum exploring how economies can be made to work for progress, people and the planet. I'm Natalie Pierce and with me is the co-author of the book Stakeholder Capitalism, Peter Vanham.

In today's episode, we'll be exploring the social contract, that many people believe has been broken, between governments, business and workers. The theme of today's episode is 'an economy that works'. Traditionally, workers have had their voices heard and advocated for their rights through collective bargaining and unions. However, both the membership and power of unions seems to be on the decline around the world with some pretty serious consequences. Peter, can you present the problem to us in a nutshell?

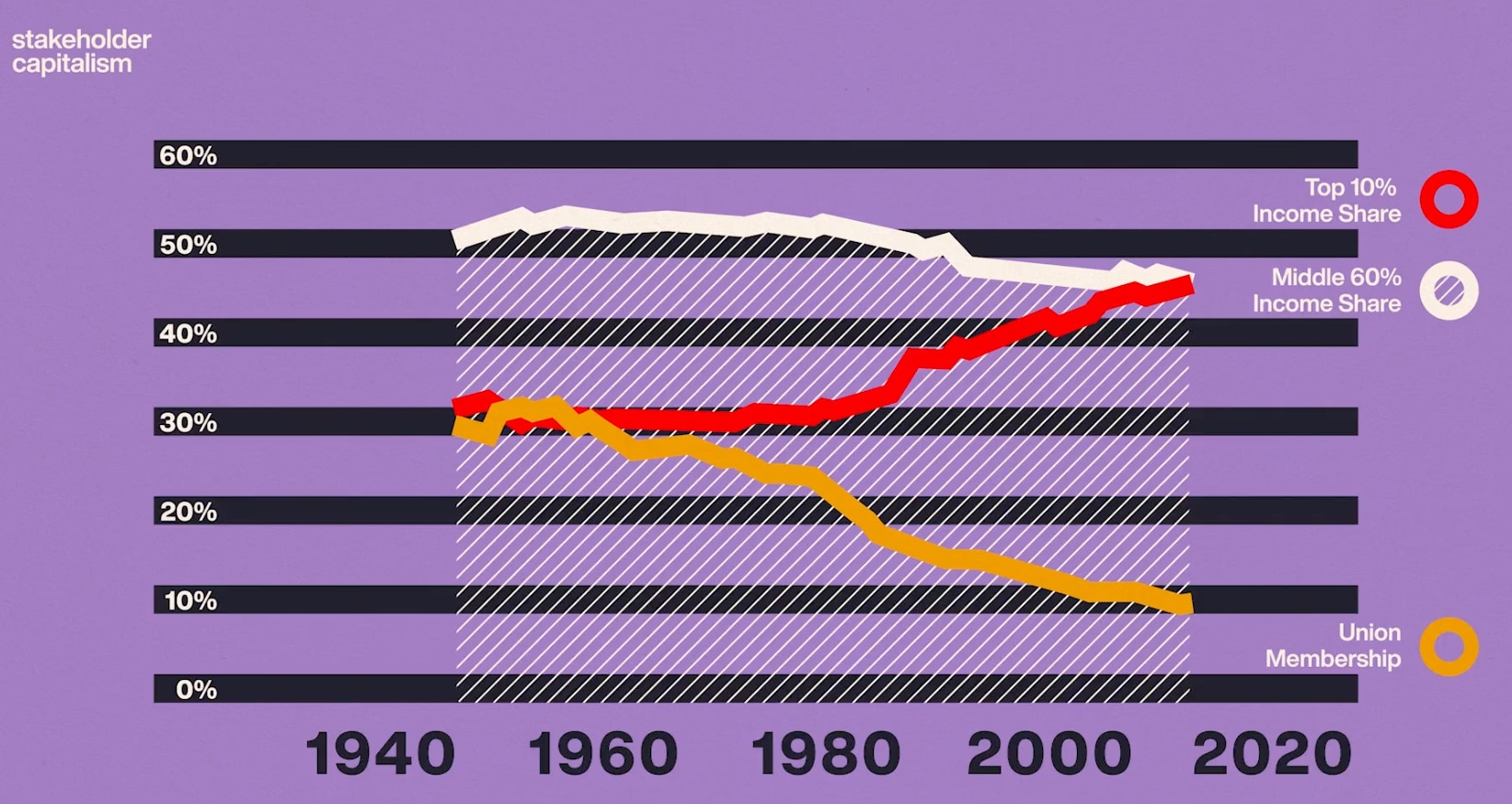

Peter Vanham: Let's have a look at what happened with union membership over time, and let's look at the United States in the last 60 or 70 years. There we see in the 1950s to 1970s, this was the 'golden era' of capitalism, well it coincided with the golden era, you could say, of unions: more than 30% of people were members of unions. But then it started to trail off, particularly in the 1980s, 90s and 2000s. This was when there was a strong political movement against unions. And down today only 10% of US workers are members of a union.

That coincided with a declining share of income going to the middle class, the middle 60% percent of income earners. At first, they earned well above 50% of US income. But then, when union membership started to fall off a cliff, the same thing happened, although less dramatically, with the middle income share. And of course, a mirror image of that is the top 10% income share - the richest income earners. They at first had an income share of about 30% and then as that golden era of capitalism was over union membership started to drop. You could see that rising share of income for the top 10%.

Natalie Pierce: So we see a decline in the income of the middle class, and we also see a decline in union participation. But correlation does not always mean causation of course. Around the world over the last four decades, we've seen a significant decline in middle income. Well, of course, we know that the top 1%, the top 10%, their incomes have skyrocketed.

Peter Vanham: That's right, you do see that global trend of the rising incomes of the top 10% of the top 1% and declining income of the middle class. But where it gets really interesting, Natalie, is that in some countries we do observe also a positive correlation between where union membership remains high and middle-class incomes remain much higher than elsewhere in the world. And one case in point is Denmark, in the Scandinavian countries.

Natalie Pierce: Before we look at that example from Denmark, let's go first to the United States and explore what this means for workers there. Our first expert guest is Heather Long. She is an economics correspondent at The Washington Post, and she reports regularly on economic policy and travels across the country to explore its impacts in factories and other workplaces.

Heather, we just heard from Peter indicating a decline in middle class incomes. Can you tell us in your visits on the ground, what does this look like in practise?

Heather Long: It's a huge issue across the United States when the unions go away, usually because an auto factory or some other manufacturing hub closes, people go from earning on average pretty middle-class income - around $30 dollars is average in a lot of the union areas. And what replaces those jobs is usually something like warehouse work, which pays OK, better than fast food or retail, but it generally means an income cut. Imagine losing 50% or more of your income. All of us would suffer. It's a huge lifestyle change. People go from being able to afford that car, to afford a housem and afford to send their children to college, to living a paycheque-to-paycheque lifestyle.

Peter Vanham: That's really worrying. And what do you think are some of the structural trends that explain what happened?

Heather Long: Unfortunately, in the United States, we've tended to see that companies will just get rid of their current workers or try to find ways to get rid of the current workforce and bring in different people by moving the factory, either overseas for lower cost, or even to other parts of the United States. There's been this big migration from, say, the Upper Midwest - the Wisconsin, Ohio, Michigan area - down to states like South Carolina, where it's easier to avoid unionisation. The wages can be lower and they get, in some cases, a younger workforce in that part of the country.

Peter Vanham: What you found I thought was interesting was that even when these people that are unemployed or lost her job were offered retraining that very often they didn't sign up for it or they sign up for the very basic courses. What explains that?

Heather Long: The United States does offer some fairly substantial worker retraining opportunities where someone can basically get up to two years of college paid to do a lot of retraining. I spent a lot of time in a town called Lordstown, Ohio, where a General Motors plant famously closed in 2019. And it was really striking to me that what I found is workers under 45 tended to do well. One woman was like, 'I'm almost glad I got laid off. I got my nursing degree paid for and now I have a new profession'. But anybody I spoke to who was 45 and over - I just remember a heartbreaking discussion with with a man who was very smart and I'm talking to him over his dinner table. And he said, 'I used to do engineering-type jobs at the plant, but I have spent a week in this community college class and I had to drop out because I didn't even know things like where the thumb drive was'. They just haven't been in the classroom for such a long time. It was too big of a leap. And also in the United States, people were hesitant to move. So I also noticed that General Motors would, for instance, ask people if they wanted to moved to a different state to perhaps work in a plant in Texas. And that's really hard. Again, it was a generational divide where people who were young, in their 20s, didn't have kids, they were generally willing to try something new, maybe even saw it as an adventure. But anybody who was sort of in that mid-30, and certainly by the time you got to 40s, it was just really hard, you know, to snap and changed your life.

Peter Vanham: What are we missing here, then? Because we saw sort of a correlation between declining middle class incomes and the declining membership of unions. But what you seem to suggest is that even when unions are present and even when the retraining is present, you still see that sort of negative spiral that people get into. Are we looking in the wrong place to look at the role of unions?

Heather Long: in my own industry, in journalism and media, we've actually seen a resurgence of unions in the past few years. So I think some people certainly still buy into unions and the importance of unions, but it has just diminished over time. And we're I think we're at that point where it's only one in 10 workers are unionised these days. And I think this new generation that's coming up of people in their twenties and thirties, while they would agree with you and your premise that we could use more unions in the United States, it's hard to start them. And we just saw that with the case in the Amazon warehouse that vote down in the South. A lot of people were stunned that the workers did not vote to unionise, and it was almost two to one voting against unionisation.

Natalie Pierce: Why do you think, Heather, that unions are so polarising in the United States right now?

Heather Long: Right or wrong, unions over time had become very associated with the Democratic Party, and they tended to tell their members to vote for Democratic candidates at both the state and local level, as well as for president of the United States. What was fascinating to a lot of people was in the 2016 election of Donald Trump, he did way better than most Republican candidates with unions here. He talked about unions. He visited several unionised warehouses on the campaign trail and really made a lot of inroads with the population we're talking about of people who felt that their livelihood was at stake, whether they were a union member or someone who had seen that company move out of their town.

Peter Vanham: One other thing that you touched on was this notion that we have also new jobs. We're seeing now a gig economy. It seems much harder for people to represent themselves if they're not physically in the same workplace as everyone else, as was the case in in factories. So how do you see the future there for the gig economy and its workers?

Heather Long: There was a huge case - a vote - in California. It's called Proposition 51, I believe, it was basically around rideshare - what benefits and rideshare drivers have for the Ubers and Lyfts and other types of these services. The companies really didn't want these workers to even be classified as they are workers. They want them to still be considered independent contractors who are just using the brand of an Uber or Lyft, but are basically running their own business out of their own car. And they made this small compromise where there was an opportunity if you drove a lot - say, over 30 hours a week - you could potentially get certain types of benefits, maybe an access to a health care plan or access to various other retirement type savings plans. But but it's pretty far from what you're describing, from looking like anything like a workforce or just a relationship with your company that many of us are used to.

Something that surprises me, at least in the United States we all think that the gig economy is growing so large. In actuality, certainly, the government data in the United States indicates that the gig economy actually has not grown as much as many of us perceive, and it's still a very small share - 10% or less share of the labour force right now. And so it's not just the factory jobs and those blue collar jobs that have declined substantially United States, it's also low to middle-skill office jobs. So when we talk about women, women who often worked as filing clerks, paralegals, administrative assistants, those also used to be those sort of middle class jobs in the US that would pay sort of $40,000-$60,000, come with good benefits. And those have dramatically gone away from the automation trend. And so basically, we've seen this hollowing out of jobs in the US that pay between $30,000-$60,000 - that middle class pay. And they're being replaced by a lot of jobs - of the top-10 fastest growing jobs, seven pay less than about $27,000 a year, certainly under $30,000. So when you lose one of these jobs, you're left: 'Do I have to go back and get a college degree and try to get in the white collar economy?', which is a big, scary leap for a lot of people. Or do I take - your best option is usually a warehouse job right now.

Natalie Pierce: What solutions are you seeing or policies recommendations that leave you optimistic?

Heather Long: I think a couple of things. Number one, that I hands-down think has been the best programme the United States. It's two years of free community college, People knowing that they can go back and do two years pretty much at any point in their life is a huge game changer. But this is one of those bipartisan policies. So blue states like Rhode Island, red states like Kentucky have tried this, and it's been hugely successful because people know it's there. You can literally just drive to your nearby community college or go online and talk to them. Same thing with high-skilled manufacturing, those courses are about a year long and can be a game changer. It's that barrier to entry you're just trying to lower and when people know it's open to everyone it does seem to increase enrolment and increase people finishing these projects.

Peter Vanham: Do you think that that the missing link then is not just that the policies are there and that the educational opportunities are there, but also that there's this culture in which workers feel confident to go and pursue those opportunities? And is that then perhaps the new role of unions or whatever the equivalent of that is in the new economy?

Heather Long: It has to be more than the educational opportunity. That's always the easy solution. And I will say, whether it's done through a union or we're starting to see this proposal in the United States from the Biden administration for a big expansion of the role of government. And what they're talking about is more of the European style role of the government, where they're not just helping you educationally, but they're also helping provide child care, helping provide universal care for three and four year olds. The other thing they bring up is transportation, and it's been interesting to see that cities where there's a real discussion about where the bus routes should be, whether to subsidise and how that could change where people can go and what their job options are.

So I think this holistic thinking about work and what work looks like and what workers need to get back into the workforce is key. And the last point I'd throw out for the US is mobility, not just mobility of job or mobility and income, but Americans don't move a lot. We used to be this country known for immigration, for people being willing to uproot their lives and comes the United States. But in the past 50 years, people are really hesitant to move more than about 30 miles. And with the whole rise of cities, with the changing types of jobs you can do, there's been a big debate in the US. Do you try to save some of these cities that are not near that eco-system. Or do you try to move the people to where you see the future and where you see these newer job opportunities? And that's a really hard debate.

Natalie Pierce: Thank you so much for being with us, Heather.

Up next, we're going to welcome our second expert witness who comes from Denmark, Peter, before we get to it, why is Denmark such an interesting example for today's conversation?

Peter Vanham: Well, it's a country where the union membership has remained very high and, at the same time, incomes of the middle class have remained very high. And finally, also it's remained a very competitive and open economy.

Natalie Pierce: To tell us more, we have Thomas Søby, who is the chief economist of the Danish metalworkers union.

I have a first question: there was a quote in the Stakeholder Capitalism book that I really enjoyed, it said: you should not be afraid of new technology. Instead, you should be afraid of old technology. And it was said by the president of the Danish metalworkers union. What do you think of this quote and do you agree with that?

Thomas Søby: I absolutely agree. Not just because it was our president who said it, but also because I think it's true. Denmark is a small, open economy. We are very exposed to global competition. So without new technology, we would lack the ability to compete on the global markets. So productivity and competitiveness is one part of it. And the other part of it is, of course, that it improves working conditions. New technology can help us to get rid of heavy lifting and stuff like that. So it's it's pretty much a win-win. It's good for the companies and it's very good for our members that we have new technology that improves productivity and working conditions.

Peter Vanham: You're speaking as if you could also be the chief executive of a company. You talk about win-win - a win for workers and a win for companies. Could you tell us a little bit more about the social pact that exists in Denmark between companies, workers and governments?

Thomas Søby: I don't know if I could go as far as calling it a 'pact'. But I think there's a mutual understanding that we are dependent on each other. It is very easy for companies to hire and fire people. So that's the flexibility part of the system. But there's a great means of social security as well. That's the security part of it. And it makes it better for the workers when they are laid off to get education, retraining and also a sum of money in order to keep up with living standards. And then we have the third leg, and that is the public-financed educational system creating an educated workforce pretty much able to step right into a specific company and do the jobs they are asked to do. And that makes it the 'flexicurity' system, also known as the Danish or the Scandinavian model.

Peter Vanham: And that makes you embrace technological progress because you know that if something goes wrong, if you might lose your job temporarily, you will be receiving help and you will be receiving training. When we talked to Heather Long in the US, she saidthere were places where training was offered, where education was offered, but workers didn't even sign up for it, she said, because they had been out of the classroom for way too long. What makes a Danish model different? Why are workers so much more encouraged and enthusiastic to participate in the education?

Thomas Søby: Well, we do have some kind of problems as well with with workers more reluctance to participate in education. But I think the general rule is that they are pretty eager because they know that new technology makes them need new skills. And if you are to keep your job, you just need to improve your knowledge and improve your skills.

Peter Vanham: You really see that that's a difference in Denmark - people get retrained continuously, maybe every year, every couple of years. Whereas in the US there's often a much bigger lag in terms of that education taking place. But also wages are much lower, we heard from Heather, in the US. What do you think went wrong in the US that they don't have that model anymore?

Thomas Søby: I'm not a specialist in the American economy, but what I think there's a couple of things that went wrong in the US. I'm afraid that the degree of the workforce who are members of a union is just about 10% today. I think it's at least 70% in Denmark. So the unions don't have the force to make it available for the workforce to get more education. Instead, they have used their abilities to try to compete in low-wage systems where we in Denmark are trying to compete with high quality, high productivity. And Denmark is a high salary country. It is expensive to have a business in Denmark. And of course, we have disagreements with the employees on that topic. But on the other hand, we also have a very, very, very skilled and very, very educated workforce with a very, very high level of productivity that makes it possible to compete even when when the wages are pretty high. And I think the combination of education, high taxes and of course, high productivity and new technology, makes us a more competitive economy than at least the manufacturing industry in the U.S.

Natalie Pierce: What do you say to critics who think that unions are an inhibitor to a free and open market?

Thomas Søby: I heard that point of view, and I sometimes also understand where it comes from. I think that what we have agreed upon in Denmark is that we have a rule-based labour market. So the employees, the employers, both sides know that it to mutual benefit that we have created a system with negotiations. Of course, we have the right to strike and sometimes there are strikes. But very huge general strikes are very, very rare because usually we get things solved in the local company or on a local level, or if it's necessary on an organisational level when the union meets with the employers.

Natalie Pierce: It sounds like creating space for open dialogue between stakeholders - government, business, workers, unions - is absolutely critical in your case.

Thomas Søby: Absolutely. And we have tripartite negotiations as well, and especially during the COVID 19 pandemic, we have had a lot - I think 15 or 16 three-party agreements about how to mitigate the very serious implications of COVID-19. And I think when when we look at the results so far, we've done pretty good. Very low rise in unemployment. And when it comes to manufacturing, increased exports now, increased employment again, and also a very, very low level of unemployment in the Danish economy.

Peter Vanham: Thomas, it seems that in Denmark, there's a very high sense of ownership amongst employees over the purpose of the company and the direction of the company. They want to contribute to that. In other places we've seen that feeling of ownership is much less, it's absent. What do you think are some best practises for employees to feel more connected to the company?

Thomas Søby: I think you're right. There's a huge amount of loyalty from the workforce to the specific company they work in. And I think dialogues between the company and the shop stewards and the workers are very, very key in this issue. Show interest in the workforce, help them educate themselves, talk to them about new investments, talk to them about how the company is going to to evolve. I think you get a lot in return in terms of loyalty, flexibility and a willingness to educate, willingness to do better. Invite the workers inside the decision of the company. Of course, the leadership of the company will ultimately be the deciders. But the dialogue, the discussions, the conversation about the themes of importance to the company is extremely important to have with the workforce.

Natalie Pierce: Thank you so much, Thomas, for being with us today. We are now going to move to the last part of our episode, the 'post-match analysis'. Peter, you presented the problem to us around the world. We see that workers are losing their seat at the table. What did you hear from today's conversation that makes you optimistic?

Peter Vanham: Well, I think in the first case, we heard from Heather, who said, well, even if you have no longer unions per se, you can still have, for example, government step in and play the role that unions used to play. She talked, for example, about the need for this continuous education and for education or reskilling not to be held out until somebody gets fired. So I think that whether unions, government or company, the important point is that the interests of the workers are taken into account.

Natalie Pierce: I heard that so clearly from Thomas, who said we need new alliances, we need new coalitions between government, business and workers. And this is the only way that will ensure that we don't see an unstoppable race to the bottom when it comes to labour workers rights.

Peter Vanham: Yeah, that's right. And the nice thing about the Danish example is that it shows that you can have that third seat at the table for unions, for workers, that they can be responsible. As Thomas said, there can be a civilised conversation and dialogue between workers and companies and, if needed, the government. You can actually have people all work towards that common goal and that benefits everyone in the end.

Natalie Pierce: Absolutely. We don't let anyone off the hook. Policy makers ensure that workers have capacity to organise and business leaders prioritise workers - their most important asset.

Peter Vanham: That's something that remains valid throughout time and throughout, let's say, technological revolutions. We heard also from Heather that you have this rise of the new econom, of the gig economy to a certain extent, but also things such as warehouse jobs and other types of new jobs emerging. And where you can then not organise labour in a traditional way, you have to look for new ways of getting together and organising your interests.

Natalie Pierce: Thank you, Peter. To learn more, visit weforum.org. We'll see you next time.

For the full series, visit the Stakeholder Capitalism homepage.

Find all our podcasts here. Subscribe: Radio Davos; Meet the Leader; Book Club; Agenda Dialogues. Join the World Economic Forum Podcast Club on Facebook.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Stakeholder Capitalism

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Rishika Daryanani, Daniel Waring and Tarini Fernando

November 14, 2025