3 surprising facts about global warming in the polar regions

Global warming: The North and South Poles experienced unprecedented heatwaves in 2022.

Image: Unsplash/mlenny

Stay up to date:

Arctic

Listen to the article

- The North and South Poles experienced unprecedented heatwaves in 2022 - temperatures were up to 40 degrees Celsius above the regional,l seasonal average.

- Huge tracts of boreal forests have been destroyed by wildfires in the Arctic Circle. On the other hand, Permafrost is melting, reversing the role of frozen Arctic soil as a major carbon sink.

- People living in the Arctic are leading the way in how we must all adapt to climate change.

Penguins, polar bears and perishing cold are what most of us associate with the Earth’s polar regions.

But global warming is changing those long-frozen areas at the top and bottom of the planet. We can now add subterranean wildfires, heatwaves and melting permafrost to our knowledge of the effects of climate on these desolate and fragile environments.

In many ways, the polar regions are the canary in the coal mine when it comes to climate change. The North and South Poles have become our early warning system, foretelling how humans in the rest of the world may have to adapt as the planet warms up.

Here are 3 startling facts about climate change in the polar regions - and how indigenous people are leading the way on climate adaptation.

Heatwaves in the Arctic and Antarctica

2022 saw record-high temperatures in both the Arctic and Antarctica. On 18 March, scientists at the Concordia station in Antarctica recorded a temperature of -11.8C. On the face of it, that doesn’t sound particularly warm, but it’s startling when you realize that it’s 40 degrees higher than the seasonal norm.

The 2022 Antarctic heatwave followed a similar event in 2021, leading scientists to suggest there was an increase in the intensity of extreme weather episodes in the region.

At the same time, weather stations close to the North Pole were recording temperatures 30 degrees above normal for the time of year, according to reports in The Guardian.

Zombie Fires

With temperatures rising in the polar regions, the risk of wildfires in the Arctic Circle is growing. Reuters reports that in 2021, wildfires that broke out in Siberia burned 168,000 square kilometres of boreal forest.

Arctic wildfires unleashed an estimated 16 million tonnes of carbon in 2021, according to a report by the Copernicus Climate Change Service.

While most wildfires burn out in the open, another form of Arctic fire is more difficult to detect. So-called zombie fires can smoulder in peat beneath the Arctic’s icy surface, throughout the winter months. When spring comes, the fires reignite surface vegetation, emitting carbon dioxide from both the vegetation and the peat, which is a natural carbon dioxide store. A report by climate scientists concluded that the increase in the number of these overwintering wildfires is directly linked to climate change.

What’s the World Economic Forum doing about climate change?

Depleted carbon sinks

The polar regions are warming much faster than the global average. In the Arctic, 2022 was the 6th warmest year in records that date back to 1900. This rate of warming continues an upward trend that has been going on for decades.

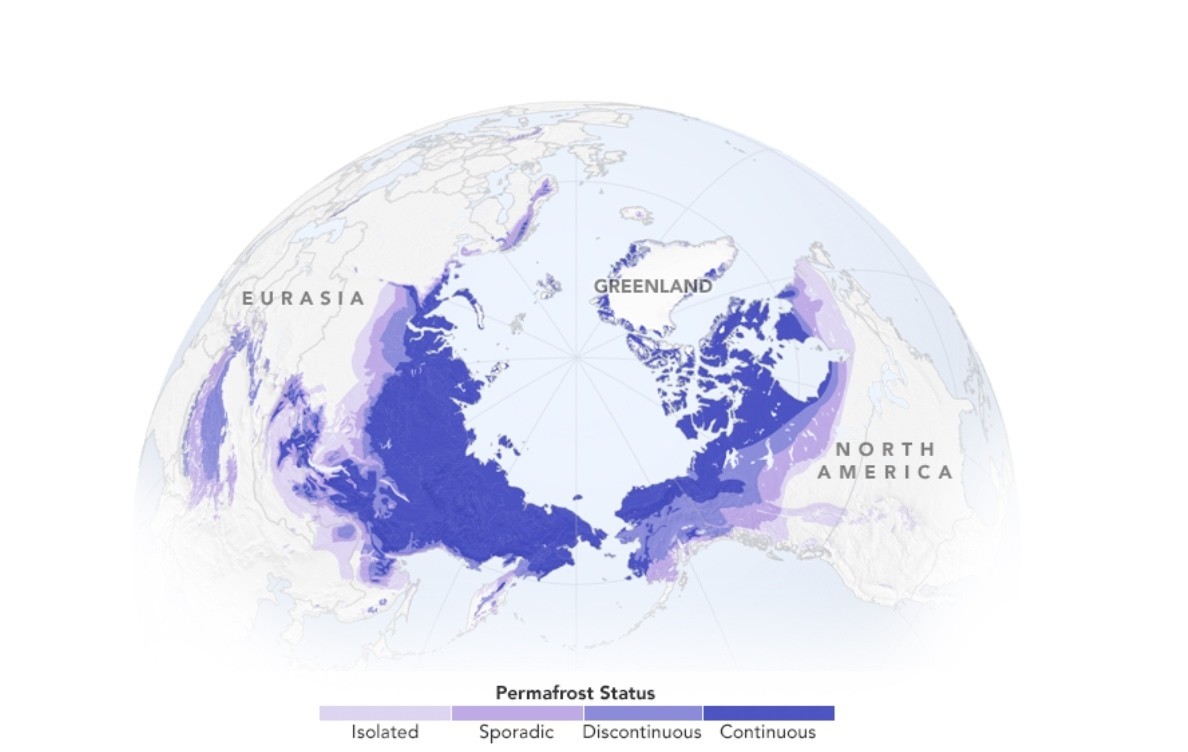

One of the consequences of Arctic warming is that permafrost - soil that has been frozen solid for millennia - is beginning to thaw. The melting of the permafrost is a double negative for the climate. Firstly, permafrost is one of the biggest carbon sinks on the planet. Scientists estimate that it stores five times more carbon than has ever been released by humans burning fossil fuels.

Secondly, scientists at NASA’s Earth Observatory partnered in a study that found the Arctic permafrost is transitioning from an important carbon sink to a major emitter of CO2. They describe the transition as; “a stark reversal for a region that has captured and stored carbon for tens of thousands of years”.

The research team concluded that: “1.7 billion metric tons of carbon were lost from Arctic permafrost regions during each winter from 2003 to 2017. Over the same span, an average of 1 billion metric tons of carbon were taken up by vegetation during summer growing seasons. This changes the region from being a net ‘sink’ of carbon dioxide - where it is captured from the atmosphere and stored - into being a net source of emissions.”

Adapting to polar climate change

The Antarctic is one of the most isolated and inhospitable places on the planet. It’s perhaps no surprise, then, that there are no permanent human settlements on the continent. At the other end of the world, the Arctic is home to four million people, many from indigenous communities.

The Arctic Council says the people of the Arctic are already feeling the effects of climate change and believes the wider world will have much to learn from the Arctic people as they adapt to climate change. The Council says: “Understanding how climate change will affect the Arctic climate system and ecosystems is key to adapting livelihoods and to inform decision-making on regional, national and international levels.”

Accept our marketing cookies to access this content.

These cookies are currently disabled in your browser.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Climate ActionSee all

Dipali Khandelwal and Hemlata Chauhan

May 19, 2025

Shyam Bishen and Lorna Friedman

May 19, 2025

Lee Poh Seng and Heng Wang

May 12, 2025