Global Risks Report 2025

Global Risks 2025: A world of growing divisions

1.1 The world in 2025

The current geopolitical climate, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and with wars raging in

the Middle East and in Sudan, makes it nearly impossible not to think about such events when assessing the one global risk expected to present a material crisis in 2025: close to one-quarter

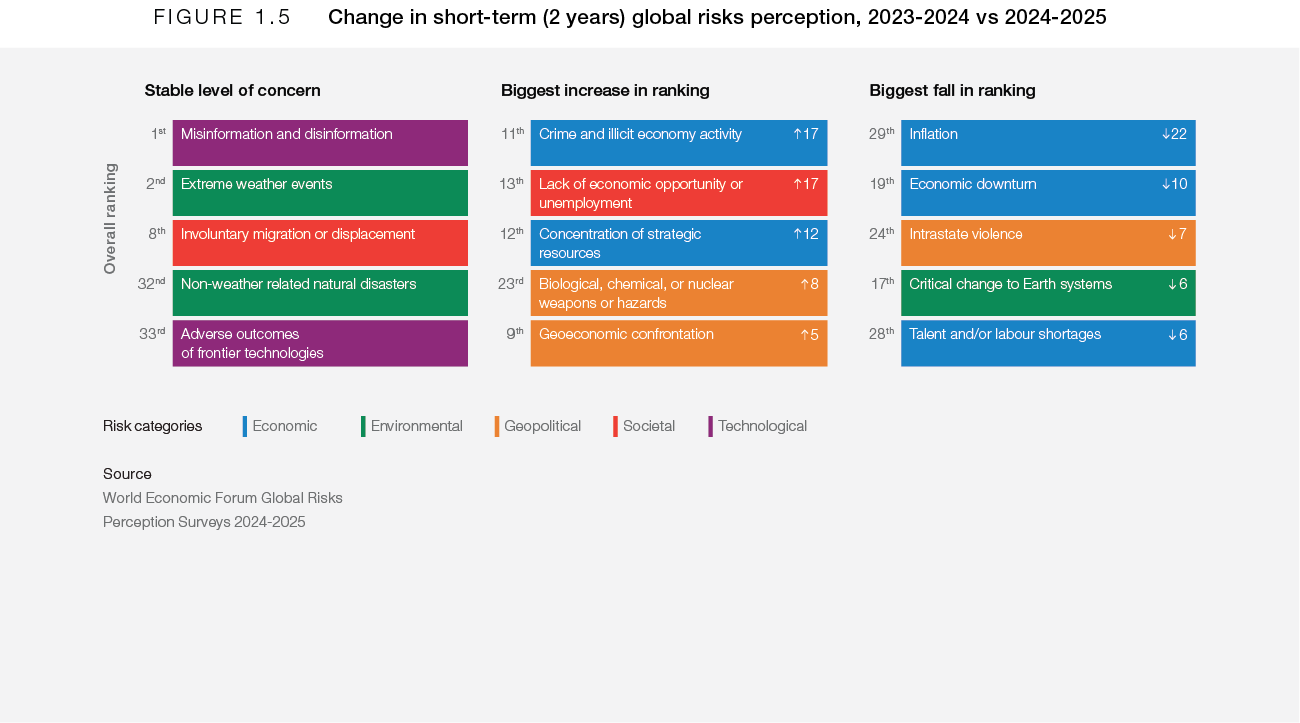

of survey respondents (23%) selected State- based armed conflict (proxy wars, civil wars, coups, terrorism, etc.) as the top risk for 2025 (Figure 1.1). Compared with last year, this risk has climbed from #8 to #1 in the rankings. Geopolitical tensions are also associated with the rising risk of Geoeconomic confrontation (sanctions, tariffs, investment screening), ranking #3, which is also driven by Inequality, Societal polarization and other factors.

The risks associated with Extreme weather events also is a key concern for the year ahead, with 14% of respondents selecting it. The burden of climate change is becoming more evident every year, as pollution from continued use of fossil fuels such as coal, oil and gas leads to more frequent and severe extreme weather events. Heatwaves across parts of Asia; flooding in Brazil, Indonesia and parts of Europe; wildfires in Canada; and hurricanes Helene and Milton in the United States are just some recent examples of such events.

Similar to last year, Misinformation and disinformation and Societal polarization remain key current risks, in positions #4 and #5 respectively. The high rankings of these two risks is not surprising considering the accelerating spread of false or misleading information, which amplifies the other leading risks we face, from State-based armed conflict to Extreme weather events.

A sense of increasingly fragmented societies is reflected by four of the top 10 risks expected to present a material crisis in 2025 being societal in nature: Societal polarization (6% of respondents), Lack of economic opportunity or unemployment (3%), Erosion of human rights and/or civic freedoms (2%) and Inequality (2%).

On the economic front, Inflation is perceived as less of a concern this year than in 2024. However, perceptions of the overall economic outlook for 2025 remain fairly pessimistic across all age groups surveyed. The risk of an Economic downturn (recession, stagnation) continues to be a common concern among respondents, coming in at #6 (5% of respondents), the same position as last year.

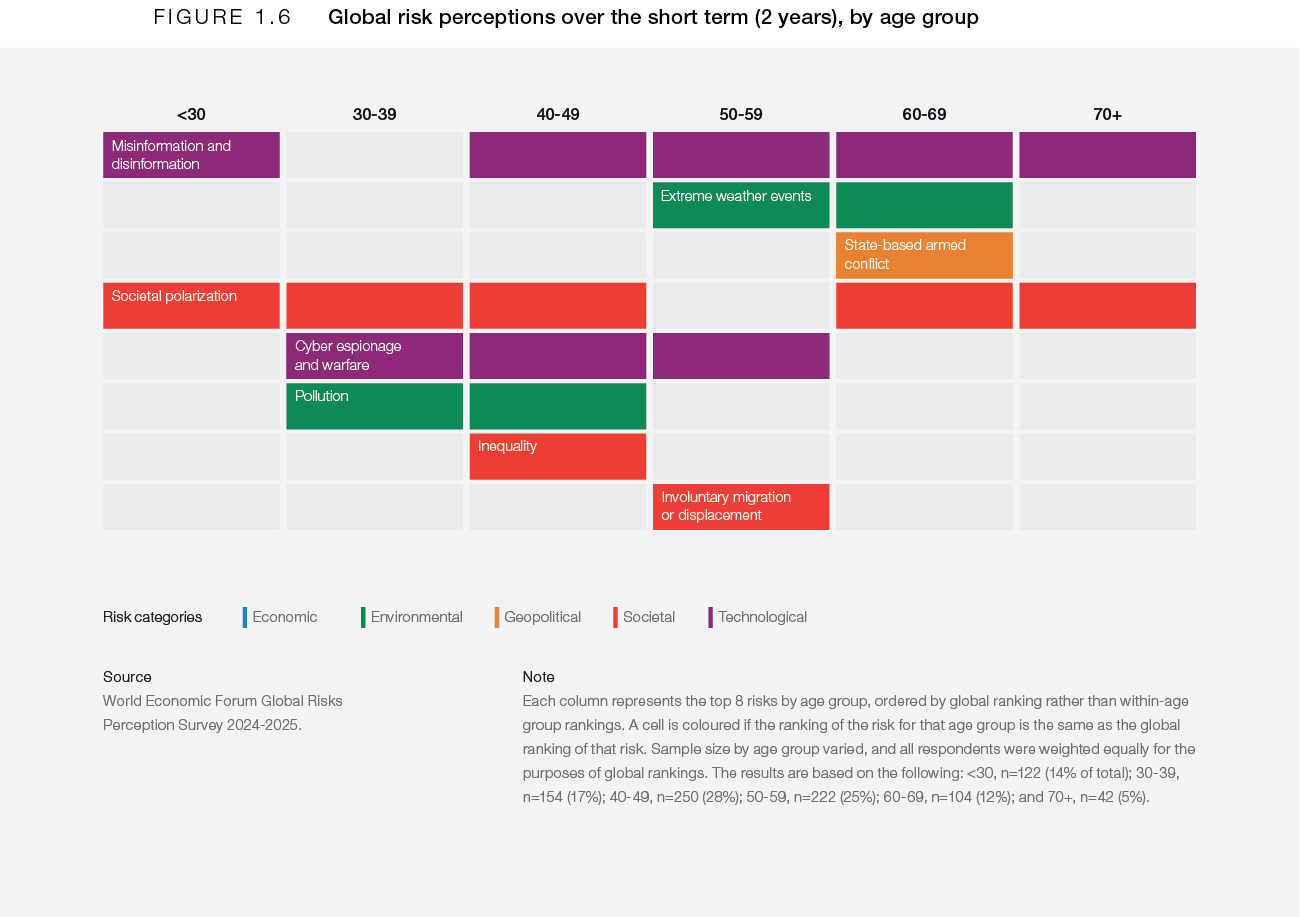

The perceived vulnerabilities associated with the Economic downturn risk are higher for younger age groups: it is ranked #3 for under 30s, #4 for the 30-39-year age group and #5 for the 40-49-year age group (Figure 1.2), but does not even feature in the top 10 for those aged 60 years or older.

1.2 The path to 2027

The global outlook for 2027 is one of increased cynicism among survey respondents, with a high proportion of respondents to the GRPS 2024-25 anticipating turbulence (31%), a four percentage- point increase since last year’s edition (Figure 1.3). There is also a two percentage-point year-on-year increase to 5% in the number of respondents who are anticipating a stormy outlook – the most alarming of the five categories respondents were asked to select from – over the next two years.

The top risk for 2027 according to survey respondents is Misinformation and disinformation – for the second year in a row, since it was introduced into the GRPS risk list in 2022-23. Respondent concern has remained high following a year of “super elections”, with this risk also a top concern across a majority of age categories and stakeholder groups (Figures 1.6 and 1.7). Moreover, it is becoming more difficult to differentiate between AI- and human- generated Misinformation and disinformation. AI tools are enabling a proliferation in such information in the form of video, images, voice or text. Leading creators of false or misleading content include state actors in some countries.

In a year that has seen the mass rollout of developments in AI and considerable experimentation with AI tools by companies and individuals, concerns about Adverse outcomes of AI technologies is low in the risk ranking. In fact, it has slightly declined in the two-year outlook, with the risk now ranking #31 compared with #29 in last year’s report. However, complacency around the risks of such technologies should be avoided given the fast-paced change in the field of AI and its increasing ubiquity. In this report we highlight how AI models are a factor in the relationship between technology and polarization. Section 1.5: Technology and polarization explores the risks for citizens resulting from the combination of greater connectivity, rapid growth in computing power, and more powerful AI models. In Section 2.4: Losing control of biotech? we highlight the role of AI in accelerating developments in this field, for both good and bad.

Respondents also express unease over Cyber espionage and warfare, which is #5 in the two-year ranking, echoing concerns outlined in the World Economic Forum's 2024 Chief Risk Officers Outlook, where 71% of Chief Risk Officers expressed concern about the impact of Cyber risk and criminal activity (money laundering, cybercrime etc.) severely impacting their organizations. The rising likelihood of threat actor activity and more sophisticated technological disruption were noted as particular concerns.

Elevated cyber risk perceptions are one aspect of a broader environment of heightened geopolitical and geoeconomic tensions, which is reflected in the two-year ranking of State-based armed conflict moving up from #5 in last year’s report to #3 now. The risk of further destabilizing consequences in Ukraine, the Middle East, and Sudan are likely to be amplifying respondents’ concerns. In a world that has been seeing an increasing number of armed conflicts for a decade, as detailed in Section 1.3: "Geopolitical recession", national security considerations are increasingly dominating government agendas. That section of the report dives deep into the dangers of unilateralism taking hold, including its implications for deepening humanitarian crises.

Overall, the GRPS risks with some of the sharpest rises in ranking compared to the previous year are geostrategic in nature. Biological, chemical, or nuclear weapons or hazards (#23) and Geoeconomic confrontation (#9) are up eight and five positions, respectively, since the GRPS 2023-24. Section 1.4: Supercharged economic tensions explores how global geoeconomic tensions could unfold over the next two years.

Private-sector concern with the two-year outlook for Geoeconomic confrontation has moved up from last year’s edition of the report, where it was not a top 10 risk; it now is #6. There is also concern among both governments and academia, who rank this risk #9 and #10, respectively (Figure 1.7).

Last year, two economic risks – Inflation and Economic downturn (recession, stagnation) – were new entrants in the top 10 ranking. Concerns around both have since subsided; in this year’s two-year risk ranking, there are no economic risks in the top 10. Inflation, which was #7 last year, has fallen to #29, with a similar decline for Economic downturn, which was #9 last year and is now #19. No stakeholder group selected either Inflation or Economic downturn as a top 10 risk, although there is ongoing concern about Debt among government stakeholders (at #7), and Crime and illicit economic activity among international organizations, private-sector and government respondents (#6, #7 and #8, respectively). Across stakeholders in the aggregate, however, there are some sharp upticks in economic risk perceptions, with Crime and illicit economic activity increasing 17 positions to #11, and Concentration of strategic resources at #12, up 12 positions from last year.

This overall mixed picture for economic risk perceptions is not mirrored in societal risk perceptions, which have risen and feature prominently in the two-year risk landscape. Inequality (wealth, income) is #7 and Societal polarization is even higher, at #4. Involuntary migration or displacement (#8), and Erosion of human rights and/or civic freedoms (#10) are also in the top 10. Lack of economic opportunity or unemployment has increased 17 positions from last year’s edition and is now #13. Inequality (wealth, income) is perceived as the most central, interconnected risk of all, with significant potential to both trigger and be influenced by other risks (Figure 1.8). The importance ascribed to this set of societal risks suggests that social stability will be fragile over the next two years, weakening trust and diminishing our collective sense of shared values. This is being felt not only within societies but also between societies and governments: the perceived risk of Censorship and surveillance (#16) is up five places compared to last year.

Fractures across societal lines are also relevant to environmental risks, which have become a more divisive issue in domestic politics in many countries in recent years. On aggregate across GRPS respondents, concerns about environmental risks are high over the two-year horizon. Respondents list Extreme weather events as the #2 most severe risk for 2027, with Pollution at #6, up four places

from last year’s report. While Extreme weather events remain a persistent concern year-on-year – the risk was also ranked #2 last year – the uptick in Pollution demonstrates that environmental

risks that are often perceived as long-term threats are starting to be perceived with more certainty by respondents as short-term realities, as their effects become more apparent. Climate change is also an underlying driver of several other risks that rank high. For example, Involuntary migration or displacement is a leading concern, at #8.

The following sections explore in-depth three risk themes and examine how these could play out over the next two years. State-based armed conflict (#3) and Geoeconomic confrontation (#9) are, respectively, at the core of Section 1.3: "Geopolitical recession" and Section 1.4: Supercharged economic tensions, while Section 1.5: Technology and polarization explores the links between Societal polarization (#4), Misinformation and disinformation (#1), algorithmic bias and Censorship and surveillance (#16).

1.3 "Geopolitical recession"

- Over the next two years, uncertainty around the course of current conflicts and their aftermath is likely to remain high, and tensions elsewhere could escalate.

- A loss of support for and faith in the role of international organizations in conflict prevention and resolution has opened the door to more unilateralist moves.

- Humanitarian crises are multiplying and worsening, given funding constraints and major powers’ lack of sustained focus on them.

State-based armed conflict (proxy wars, civil wars, coups, terrorism, etc.) was highlighted as by far the greatest risk for 2025 among the 33 risks ranked in the GRPS, with 23% of respondents anticipating a material global crisis. GRPS respondents cite Geoeconomic confrontation as well as the technology-related concerns Cyber espionage and warfare and Misinformation and disinformation among the risks most closely linked to State-based armed conflict (Figure 1.10).

Concern about this risk among respondents remains alarming on a two-year horizon, with State- based armed conflict ranked #3, increasing two positions from last year’s risk ranking.

In the EOS, Armed conflict – encompassing interstate, intrastate, proxy wars and coups – is identified as one of the top 10 global risks over the next two years. According to the EOS, this geopolitical risk ranks as the primary concern for executives in 12 countries, including Armenia, Israel, Kazakhstan and Poland, and features among the top five risks in an additional 11 economies, such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia (Figure 1.11). Executives who prioritize this risk according to the EOS frequently cite a high perception of related risks, including Biological, chemical, or nuclear weapons or hazards and Geoeconomic confrontation.

The top ranking of State-based armed conflict may also demonstrate concern among respondents that we are in what has been termed a “geopolitical recession”7 – an era characterized by a high number of conflicts, in which multilateralism is facing strong headwinds. It can also be argued that such a geopolitical recession started almost a decade ago (see Figure 1.12). Since 2014, the number of armed conflicts has been elevated compared to the period from the 1990s to the early 2010s. Interstate conflicts, while they tend to present the greatest threats to global stability, only constitute a small proportion of the total number of armed conflicts, which also include one-sided, non- state and intrastate armed conflicts.

Escalation pathways

The GRPS results are also likely to reflect the depth of respondents’ fears surrounding the two major current cross-border conflicts, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the conflict in the Middle East, and perhaps also concern around the risks of conflict over Taiwan, China.

Regarding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the position taken by the new US administration will be critical to its evolution. Will the United States take a firmer stance towards Russia, counting on such a move acting as a deterrent to further Russian escalation, and/or will it increase pressure on Ukraine, including reducing financial support? In the latter case, European governments might increase their own support for Ukraine. The spectrum of possible outcomes over the next two years is wide, ranging from further escalation, perhaps also involving neighbouring countries, to uneasy agreement to freeze the conflict.

In the Middle East, any shift towards a full-scale Iran-Israel war over the next two years would draw in the United States further. Such a war would, in

turn, generate more long-term instability in the entire region, including the Gulf economies, where US military bases could become targets. Meanwhile, recent political developments in Syria raise both opportunities and risks. Hopes are high that there could be a revitalization of the economy and a more inclusive political environment. However, building stability across Syria will be challenging, given the many competing interests that are involved. These include both domestic groups and foreign states; if other countries decide to intervene more heavily while the transition unfolds, this could lead to renewed confrontations.

In addition, conflict over Taiwan, China cannot be ruled out. Limited armed confrontation could be triggered more easily if global tensions are high around geoeconomic confrontation and if rhetoric is aggressive. Both the United States and China may go further in the coming years in undertaking military manoeuvres close to Taiwan, China designed to show strength and act as deterrent. A major risk is that just one such manoeuvre could be misinterpreted by the other side and/or lead to accidental loss of life or destruction of hardware, leading to tit-for-tat military escalation.

Waning appetite for multilateralism

With the world facing this wide spectrum of ongoing armed conflicts, and escalation risks in the two major cross-border conflicts, the current weakness of the multilateral security framework with the UN Security Council (UNSC) at its core is alarming. The UNSC has not managed to stop conflicts from escalating, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the wars in the Middle East and in Sudan.

Despite discussions over the last year about reinvigorating UN peacekeeping operations, these are in decline on aggregate, with their size having been reduced from over 100,000 peacekeepers in 20168 to around 68,000 in 2024.

The UNSC faces ongoing structural challenges,10 and over the next two years risks having even less impact, given the new US administration’s likely less favourable stance towards the UN generally and its preference for seeking solutions to conflicts unilaterally. There is a danger that more governments lose faith not only in the UNSC, but in multilateralism as a forum for resolving conflicts, and that the world instead becomes more adversarial, with conflicts ending only via battlefield, winner-takes-all victories and not through negotiated, multistakeholder peace agreements. While there continue to be discussions that aim towards reform of the UNSC, they are unlikely to make meaningful progress over the next two years given the complexity of aligning national interests and the current lack of political will to do so. Furthermore, there is no viable alternative global governance set-up in sight.

The growing vacuum in ensuring global stability at a multilateral level will lead governments around the world increasingly to take national security matters into their own hands, coordinating security and defense efforts only with select allied countries, or making unilateral military decisions. More countries will attempt to gain a greater degree of autonomy and self-sufficiency. Defense budgets could be prioritized over other long-term investments, placing at risk spending in areas such as healthcare, education and infrastructure. This accelerating military spending would represent a continuation of recent trends: World military expenditure increased for the ninth consecutive year in 2023, reaching a total of $2.4 trillion,11 with 2023 seeing a steep rise over 2022 (see Figure 1.13). The top five countries accounted for 61% of the total. As governments with strengthening militaries perceive that multilateral constraints on unilateral military action are weaker, there could be more instances of cross-border military interventions in the coming years.

Unilateralism and the dominance of national security considerations in political agendas may also have increasingly far-reaching repercussions for state-society relations worldwide. Increased state surveillance of citizens and restrictions on individual freedoms may become more commonplace in the name of national security. Perceived or actual threats from other countries also provide an opening for governments to seize control of narratives and suppress information, perhaps blurring the lines between genuine security considerations and political expedience. Governments may take measures that diminish the transparency of public expenditure, for example when it comes to funding parties to a conflict abroad. These are all conditions that will help authoritarian regimes consolidate their power and may lead to democratic regimes taking on more authoritarian characteristics.

Worsening humanitarian crises

Even beyond global security considerations, multilateralism appears set to endure its most difficult period since the founding of the UN in 1945. Over the next two years, more questions are likely to be asked by national governments about the roles and priorities of key multilateral institutions, and there could be constraints placed on their funding. The outlook for this broader weakening of multilateralism is associated with declining global budgets for humanitarian aid (see Figure 1.14).

Declining funding translates into an acute risk of humanitarian crises deepening. Global humanitarian efforts are highly dependent on the financial and human resources and institutional know-how provided by the UN. This know-how, in areas such as logistics or relationships with local governments and NGOs, has been built up over decades and is irreplaceable over a short- or even medium- term time horizon. Over 90 million people in need receive humanitarian aid or development assistance from UN institutions on an annual basis. A rising number of these individuals, as well as others who also need support but are unable to access it, will be at increasing risk of insecurity, disease, malnutrition and starvation over the next two years if UN institutions and the humanitarian sector overall are weakened further.

Furthermore, higher levels of desperation will in some settings create more opportunities for armed groups to recruit. Countries in which serious humanitarian crises risk deepening further over the next two years and in turn fueling more violence include Sudan, Mali and Haiti. In Sudan, the domestic and regional impacts of reduced agricultural production and exports are already far-reaching. Like Ukraine, Sudan is a large exporter of agricultural products. It plays a critical role for neighbouring countries Ethiopia, South Sudan, Chad and Egypt.

Forced displacement is also set to rise as international humanitarian aid efforts struggle to keep up. It is already at an all-time high, with over 122 million forcibly displaced people globally,14 and 56% are displaced within their own countries. Among the 44% who are cross-border refugees, three quarters are hosted in low-income countries that have limited resources to support them.

Sometimes refugees are confronted with nationalist sentiment or identity-related violence because of their ethnicity or religion, further fueling the potential for conflict in border areas. Increased competition for jobs between refugees and locals can also be a source of tensions.

Rising unilateralism will have softer implications, too. Societies are developing more disinterested mindsets when it comes to conflicts and humanitarian crises

in which their own citizens are not involved. As local media deprioritize reporting on “far-away” conflicts, a self-fulfilling cycle emerges, with greater tolerance by governments and societies of civilian casualties in warfare. This is a risk that has already started unfolding with respect to current conflicts, for example when it comes to Sudan: This war

has rarely been at the top of global policy agendas despite its huge humanitarian toll. Such disinterest makes internationally coordinated humanitarian responses more difficult, especially when combined with the prevailing geopolitical and funding conditions.

Actions for today

Support multilateral institutions

The GRPS finds that the approach that respondents believe has the most long-term potential for driving action on risk reduction and preparedness regarding State-based armed conflict is Global treaties and agreements (Figure 1.15. See also Figure 1.16), followed by Multistakeholder engagement.

These findings strongly suggest that it is critical for public, private and civil society stakeholders across all countries to work together to reinforce existing multilateral institutions wherever feasible. This includes the UN Security Council; despite the challenges and complexity of reforming it, governments should continue dialogues with that ultimate objective in mind.

In highlighting the benefits of multilateralism in conflict resolution, leaders should draw on case studies of resolution of seemingly intractable conflicts. An example was the Colombian government’s peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in November 2016. Broad international cooperation has also helped to tackle armed threats, for example in combating piracy off the Somali coast over the course of many yearfrom 2008. Global leaders can draw optimism from such examples and showcase lessons learned and actionable strategies for ending current conflicts.

B. Expand the role of regional organizations in managing tensions

Amid the current challenges facing global multilateralism, there is space for regional organizations to expand their roles in managing geopolitical tensions in their regions. The African Union is a good example: It already has a track record in this regard, having carried out several peacekeeping operations across Africa and on other occasions has played a mediator role. Nonetheless, there is a need for it to play a greater role in future in both peacekeeping and mediation.

C. Diversify supply chains

For organizations, one of the big lessons taken from the ongoing conflicts is the need for supply chain resilience and diversification. With geopolitical volatility likely to remain high over the next two years, organizational investment in geopolitical risk foresight and risk management is a must. When the level of uncertainty around conflicts or potential conflicts is high, scenario planning exercises can be a valuable tool to help organizations prepare for a range of different outcomes. Organizations need to consider not only whether their suppliers and supply routes are vulnerable to conflicts, but also what the reputational risks are of partnering or doing business with counterparts that are in any way party to a conflict.

- A worldwide escalation of broad tariff-based protectionism could lead to global trade declining.

- Deeper decoupling of trade between West and East would have worldwide repercussions, even beyond trade relationships.

- With economic growth in China and Europe already weak, an escalating trade war will introduce additional uncertainties into the global economic outlook.

Global trade relations are tense and there is a risk of unpredictable and potentially sharp changes in trade policies worldwide. Geoeconomic confrontation (sanctions, tariffs, investment screening) ranks #3 for current (2025) risks according to the GRPS and #9 over a two-year horizon. This comes after trade tensions have already been rising steeply since 2017. According to Global Trade Alert, the number of harmful new policy interventions per year rose globally from 600 in 2017 to over 3,000 in each of 2022, 2023 and 2024.

The incoming US administration has suggested that it will implement higher tariffs on imports from all trading partners, often singling out China, as well as Mexico and Canada. While these statements may have been the opening gambits ahead of future negotiations covering trade and other issues, they undoubtedly are a signal to the rest of the world that deepening protectionism is on the agenda.

US trading partners are considering retaliatory measures, as well as the timing for potentially implementing them. Over the next two years, there is a significant risk of escalating tariffs and other trade-related protectionism globally, which could accelerate broader decoupling between the United States and China, and their respective allies. While Cold War-style rhetoric between the United States and China could ramp up and fuel trade tensions between the two blocs, even the many countries that are not aligned with either West or East would find themselves affected by these tensions.

In such an unfolding trade war scenario, initiatives currently underway could easily stall or come apart. For example, the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is more likely to face retaliation from trading partners; and efforts to cooperate in the area of digital regulation will come up against hardening negotiating positions. These and other initiatives need ongoing collaboration to keep moving forward.

Across-the-board tariffs

In a worst-case scenario for tariff escalation over the next two years, governments would decide to impose tariffs not only on those countries/blocs imposing tariffs on them, but instead on all their trading partners. This widespread imposition of across-the-board tariffs globally would lead to a substantial contraction in global trade.

This scenario could originate from an escalation of the tariff conflict between the United States and China. The latter’s dominance of global export markets is at the core of the new US administration’s concerns. Not only in the United States, but manufacturing sectors worldwide have struggled to compete with Chinese products in a range of sectors, such as solar panels or electric vehicles. While Chinese exports slowed from 2022- 2023, their growth has remained strong over a five-year timeframe.

If Chinese access to the US market is constrained by new tariffs, Chinese exports will be likely to flow to EU and other markets. But the EU has already started pushing back in selected areas of trade with China, for example imposing tariffs on electric vehicles imports from China for a period of five years in October 2024. If faced with a potential influx of Chinese imports redirected from the United States, the EU might impose new tariffs on Chinese imports.

Other regions such as Latin America could take similar approaches in the face of diverted imports as they aim to defend local industries. Over the next two years, this could lead to a pattern of rolling, progressive protectionism spreading worldwide, at different speeds in different sectors, going well- beyond bilateral tit-for-tat tariffs. Some governments would move more aggressively than others, and once the first countries impose across-the-board tariffs on their trading partners, more countries could quickly follow.

Escalation beyond tariffs

Research published in November 2024 assessed the vulnerability of 173 countries to restrictive US trade measures. The research considers key concerns of US policy-makers, including those countries’ bilateral trade surpluses with the United States, restrictions on market access for US exports, and existing tariffs, among other criteria.20 Weighing the countries according to these criteria, South Korea is found to be the most at risk for being targeted with restrictive US trade measures, followed by China, Japan, Canada and India, at the next level of risk. However, other countries and blocs are found to be at risk, too: Brazil, the EU, Indonesia, Ireland, Italy, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico and Thailand are the next group of economies.This assessment chimes with the results of the EOS, which show that geoeconomic confrontation (sanctions, tariffs, investment screening, etc.) is a prominent concern in Eastern Asia, in particular (Figure 1.18). In Taiwan, China and Hong Kong SAR, China, this risk is the third- most significant concern in their two-year outlooks. Moreover, 12 other economies, including Japan and South Korea, rank geoeconomic confrontation among their top 10 risks. While Eastern Asia may be one region most immediately impacted by new trade restrictions, broadening global geoeconomic fragmentation would affect all economies, with those likely to suffer the most ultimately being emerging markets and low-income countries.

Beyond tariffs, industrial policy is at the core of other trade-related protectionist measures. The world is already in an era of industrial policy, with a high number of non-tariff barriers impacting trade relations. Two-thirds of all harmful trade restriction measures implemented in the last five years have been subsidies, excluding export subsidies.

Legislation such as the Inflation Reduction Act24 or initiatives such as Make in India25 are a rising characteristic of countries’ inward focus and this trend could accelerate in a fragmenting trade environment. Although industrial policy can have benefits, for example addressing market failures, its risks include corruption and misallocation of resources.26 A related area likely to see escalation is more blocking of trade and investment on national security grounds, with the number of sectors classified by governments as “strategically sensitive” expanding.

As the space for a multilateral, rules-based and open global trade environment diminishes, government interventions in the private sector could be used more frequently as a form of retaliation against companies’ home governments. Employees of foreign companies could increasingly be prosecuted or have more restrictions placed on their in-country stays, and the number and size of fines imposed on companies for alleged regulatory non-compliance could be ratcheted up. Governments may make more use of sanctions targeting individuals, financial transactions and companies.

Some governments may foment more aggressive Misinformation and disinformation campaigns about goods and services from targeted countries. Results from the EOS indicate widespread concerns about the Misinformation and disinformation risk in a diverse set of countries, including India (#2), Germany (#4), Brazil (#6), and the United States (#6). Hardening public perceptions could lead to more frequent consumer boycotts of products.

Costs for companies doing business internationally will rise in this scenario. Global firms will need to navigate divergent sets of regulations in different, fragmenting parts of the world. Regulatory technology (RegTech) will be used more by governments to surveil foreign companies and ensure compliance,27 reducing the time between new regulations being imposed and the need for companies to become fully compliant. IT infrastructure as well as data security and storage protocols will continue to be adapted to national security interests at the expense of cross-border commercial considerations. Finally, international data flows and financial transactions will become more cumbersome and costly, setting back some of the rapid progress made in recent years through the implementation of new technologies.

Government-led efforts at commercial cyber espionage could become more frequent as part of efforts to tilt the playing field towards their national champions. The EOS reveals that respondents in high- income countries tend to highlight cybersecurity risk. In some of these – for example Denmark, Luxembourg and the Netherlands – Cyber insecurity is one of the top three risks. Governments may also put pressure on domestically headquartered cloud services companies to restrict access in other countries.

Such a global fragmentation scenario will weaken the kind of multilateral collaboration required in many fields. For example, coordinating regulatory efforts and mobilizing the vast financial resources needed for the green transition will become much more difficult. Technological innovations that might make a difference towards greening economies will face more impediments to being shared across borders and scaled globally. Other areas where deeper global collaboration is badly needed, such as global health, energy or infrastructure, will also be likely to see slowdowns or reversals in progress. This will leave the world less well prepared for the next global pandemic, for example, while urgent public health and broader humanitarian issues will slip even further down the global agenda. Contagion from trade disruptions could spill over into food insecurity, too. Some large cities in Sub- Saharan Africa that are reliant on global commodity markets for their food supply are particularly at risk.

Greater economic uncertainty

The World Economic Forum’s September 2024 Chief Economists Outlook found that most of the chief economists surveyed (54%) expect the condition of the global economy to remain unchanged over the next year, but four times as many expect conditions to weaken (37%) rather than to strengthen (9%). This outlook aligns closely with the latest IMF forecast, which has economic growth stable at 3.2% annually in 2024 and 2025. Even without accounting for the potential impacts of downside risks, this growth rate is tepid compared to the long-term average growth rate of 3.8% from 2000-2019.

The IMF notes rising risks to the economy posed by conflict escalation, tariffs and trade policy uncertainty, lower migration, and the tightening of global financial conditions. The latter could pose a challenge to financial stability given that valuations are elevated in several asset classes and the amount of leverage used by financial institutions is significant. The rapid growth in the private credit market is one area to monitor. More generally, both government and private-sector debt levels continue to rise globally. There have been early signs that fiscal concerns could re-emerge over the next two years as markets will face a high volume of sovereign debt supply.

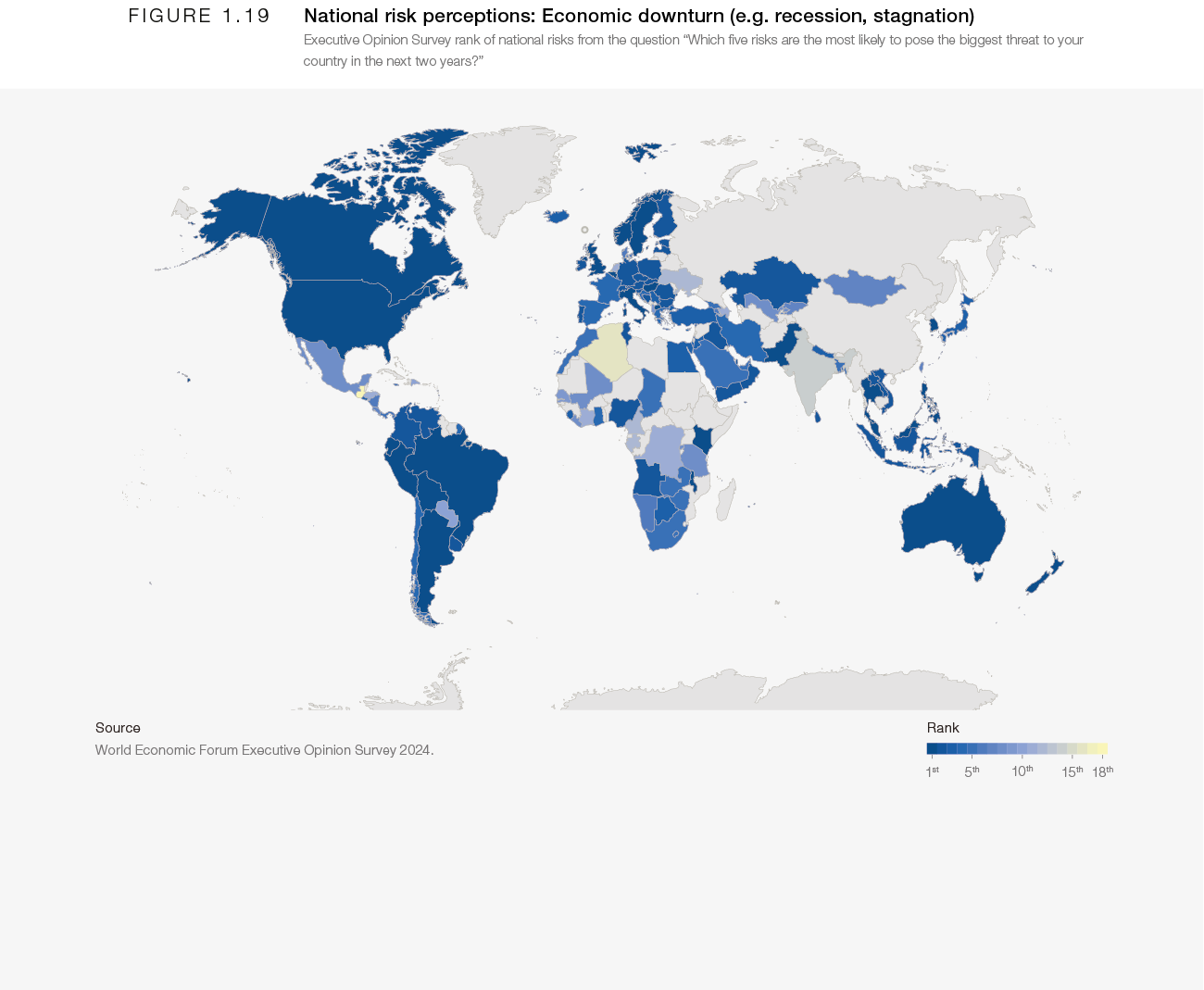

Globally, Economic downturn tops the EOS global risk ranking in the next two years. This risk ranks first in five regions: Latin America and the Caribbean, Northern America, Oceania, South-Eastern Asia and Southern Asia. It also ranks first in three out of the four country income groups, with the only exception being lower-middle income countries. Respondents in 25 countries see Economic downturn as the leading risk, including developed economies such as the United States and United Kingdom, and emerging markets such as Brazil, Kenya and Malaysia (Figure 1.19).

In the short term, higher import tariffs cause an increase in the price of imported goods. The impact on global GDP depends on factors including the substitutability between imported and domestic goods; the response of exporting firms facing tariffs; and monetary policy reactions. When it comes to the latter, monetary policy-makers are in the fortunate position of having just brought inflation back under control. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects headline global inflation to fall to 3.5% by the end of 2025, which is lower than the average in the two decades prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, one risk is that an escalating trade war will lead to another upturn in inflation, forcing central banks to halt or even reverse course from cutting interest rates. If this is associated with a strengthening US dollar, there could be knock-on risks for countries and companies with US dollar debt refinancing needs.

Indirect impacts of tariffs include a fall in productivity, due to a change in the allocation of productive resources from more to less productive, more protected sectors and firms; a rise in the cost of capital caused by financial stress; and a drop in investment due to an increase in uncertainty about future business conditions, which causes firms to adopt a “wait-and-see” approach. The latest World Investment Report, released in June 2024, cites fragmenting trade and regulatory environments as among the key drivers of a 10% slump in global foreign direct investment last year.

Analysis by the World Trade Organization (WTO) of the phase of the US-China trade conflict from 2018-2020 indicates that the direct impacts on the global economy of tariff increases during this period were far outweighed by the impacts of broader uncertainty around trade policy. With these broader impacts, the loss to global GDP was estimated at 0.34-0.50% during this period. A true global trade war would have correspondingly more severe impacts, with estimates of global GDP losses highly uncertain but potentially much higher.

The US-China trade conflict since 2018 also had clear business impacts: exits of foreign companies from China increased by 34% compared to pre- 2018 levels. Importantly, the impacts were much broader than only in the specific sectors targeted by US tariffs on Chinese products and affected non- US companies as well as US companies. These findings suggest that even the “scalpel” approach – levying tariffs on specific sectors – does not have a well-targeted outcome in terms of either sector or geography. To reiterate, a broader global trade war would magnify these impacts on businesses.

Actions for today

A. Foster multilateralism

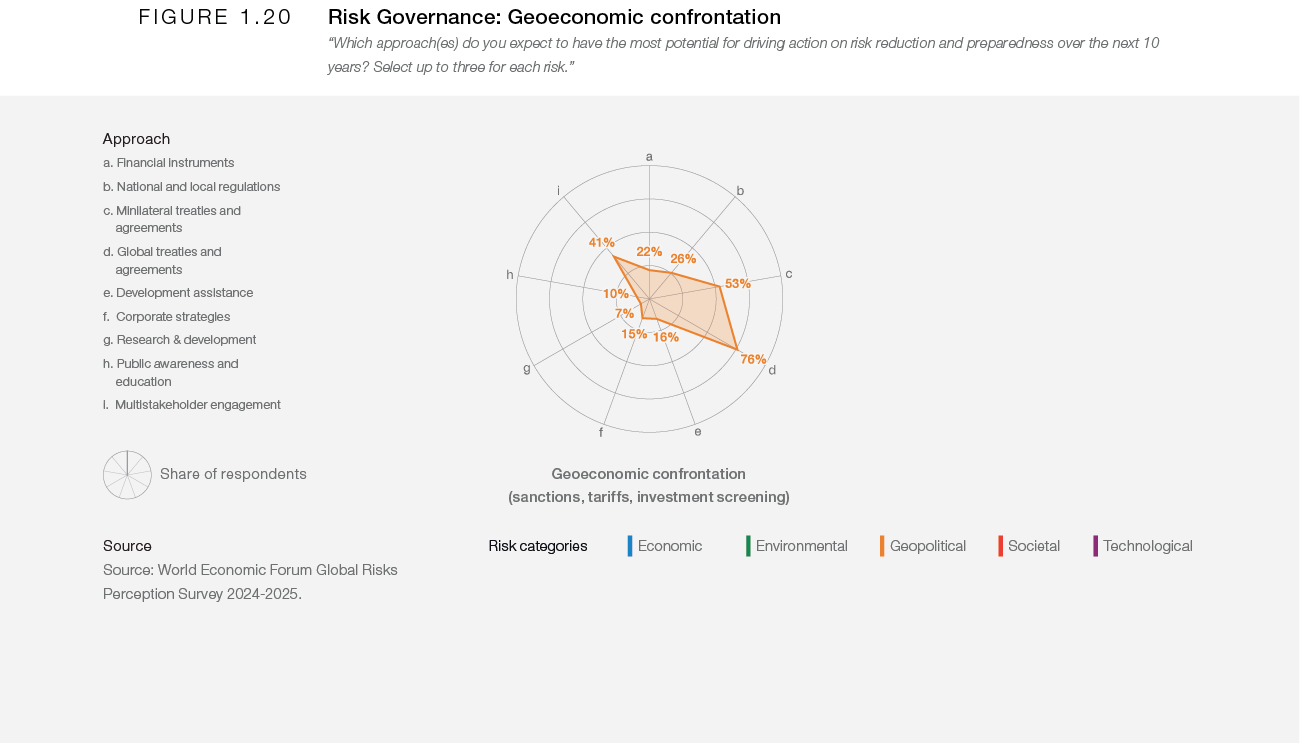

The GRPS finds that the approach that has the most long-term potential for driving action on risk reduction and preparedness regarding Geoeconomic confrontation is Global treaties and agreements (Figure 1.20). A specific area to prioritize would be a revival of reforms at the WTO to address dispute resolution, tariff-setting rules and digital trade issues. With US-China Geoeconomic confrontation at the core of a fragmenting world, more opportunities will open up for rising powers, such as India or the Gulf countries, to fill the void and propose multilateral alternatives to the current global political economic order. These countries can also benefit by acting as a bridge between West and East, even though they too will suffer many of the negative impacts of the fragmenting environment. Smaller countries will face increasing pressure to align with the West or the East in their trade relationships.

B. Develop strategic relationships

Governments could consider further prioritizing efforts to develop strategic regional or bilateral ties with countries that offer complementarity in terms of sectoral strengths, natural resource endowments and skills. “Deep” regional trade agreements – outside the WTO but consistent with WTO requirements – and WTO-based plurilateral or “minilateral” agreements can be considered (Figure 1.21).45 Even at these levels, multistakeholder dialogue needs to be deepened to reinforce the message that well- designed deepening of trade can lead to mutually beneficial economic and social outcomes.

Strengthen domestic economic resilience

In an environment where trade becomes more costly and cumbersome, emphasis needs to be placed on policies that strengthen the domestic economy, such as financial sector development or investment in education, health and infrastructure. On the supply side, developing greater self-sufficiency in key strategic sectors such as Energy, Agriculture, and Defense will increasingly become an important aspect of resilience at the national level.

1.5 Technology and polarization

- Rising use of digital platforms and a growing volume of AI-generated content are making divisive misinformation and disinformation more ubiquitous.

- Algorithmic bias could become more common due to political and societal polarization and associated misinformation and disinformation.

- Deeper digitalization can make surveillance easier for governments, companies and threat actors, and this becomes more of a risk as societies polarize further.

An estimated two-thirds of the world’s population – 5.5 billion people46 – is online and over five billion people use social media.47 The increasing ubiquity of sensors, CCTV cameras and biometric scanning, among other tools, is further adding to the digital footprint of the average citizen. In parallel, the world’s computing power is increasing rapidly.48 This is enabling fast-improving AI and GenAI models to analyse unstructured data more quickly and is reducing the cost to produce content. With Societal polarization ranking #4 in the GRPS two-year ranking, the vulnerabilities associated with citizens’ online activities look set to continue deepening hand in hand with societal and political divisions. Taken as a whole, these developments threaten to fundamentally undermine individuals’ trust in information and institutions.

Like last year, Misinformation and disinformation tops this year’s GRPS two-year ranking. The amount of false or misleading content to which societies are exposed continues to rise, as does the difficulty that citizens, companies and governments face in distinguishing it from true information. The interplay of rising Misinformation and disinformation with political and Societal polarization creates greater scope for algorithmic bias. If human, institutional and societal biases are not addressed, and/or best practices in modelling are neglected, the conditions will be ripe for algorithmic bias to become more prevalent. Such bias, whether inherent in data, models or their creators, can lead to unjust outcomes.

Despite the dangers related to false or misleading content, and the associated risks of algorithmic bias, citizens need to strike a balance between privacy on one hand and increased online personalization and convenience on the other hand. While data governance and regulation vary worldwide, it is becoming easier for citizens to be monitored, enabling governments, technology companies and threat actors to reach deeper into people’s lives. Those with access to rising computing power and the ability to leverage sophisticated AI/GenAI models could, if they choose to, exploit further the vulnerabilities provided by citizens’ online footprints. Rising political and Societal polarization could become more of a driving force for such increased surveillance.

Misinformation and disinformation in a polarized world

The advent of new technologies and the increase in user-generated content platforms is leading to a corresponding rise in the volume of content online. Flows of Misinformation and disinformation from those creating it are becoming more challenging to detect and remove in an increasingly fragmented media landscape.

Differentiating between AI- and human-generated false or misleading content – in the form of video, images, voice or text – can be difficult. GenAI lowers the barriers for content production and distribution, and some of that content is inaccurate. Threat actors, state agencies in some countries,49 activist groups, and individuals who may or may not have criminal intentions can automate and expand disinformation campaigns, greatly increasing their reach and impact.50 Misinformation and disinformation can also be the result of AI-hallucinated content or human error, and these too are likely to rise amid the growing volume of content.

The upshot is that it is becoming increasingly hard to know where to turn for true information. Both political and Societal polarization skew narratives and distort facts, contributing to low and declining trust in media.51 Across a sample of 47 countries, only 40% of respondents said that they trusted most news.52

According to the EOS, respondents in high-income countries are generally more likely to express concern about the risk of Misinformation and disinformation over the next two years than respondents in lower-income countries, with some exceptions. This risk ranks among the top five in 13 countries, including India, Germany and Canada, and features in the top 10 in 30 additional countries (Figure 1.23). Respondents identifying this risk often also highlight Societal polarization as one of the most severe risks in the same timeframe. Poor quality content and lack of trust in information sources continue to present a threat to societies.

Algorithms, especially complex machine learning models, can also be an entry point for cyberattacks that use disinformation. An example of this would be a structured query language injection attack, in which inputs are manipulated to generate incorrect outcomes or to compromise training data sets.54 As many models lack transparency, either by intention, by accident, or because of intrinsic opacity, it

is difficult to identify vulnerabilities and mitigate potential threats. In addition, given the reliance of algorithms on third-party data sources, software libraries and network infrastructures, threat actors can compromise the supply chain to manipulate algorithms and cause widespread damage. Further, as algorithms come to govern or influence more aspects of society, the potential for coordinated cyberattacks using automated systems grows.

Algorithmic bias

Algorithmic bias can both be influenced by Misinformation and disinformation and can be a cause of it. The risks of algorithmic bias are heightened when the data used for training an AI model is itself a biased sample. Sometimes, the bias can be obvious. For example, in a hiring process, a set of bios used as examples of good candidates might be drawn from a pool of previous candidates, all of whom might have the same gender, race or nationality. Other times, a bias can be less obvious: for example, a model could be trained on citizens’ previous spending on education, without accounting for certain minority groups typically spending less on education. Synthetic data may be used, aiming to remove bias, but that can itself introduce new biases.

Examples of biases against citizens include waiting times for a government appointment being assigned on the basis of a questionable set of input data and criteria, or automated responses failing to respond adequately to citizens’ needs. When algorithms are applied to sensitive decisions, biases in training data or assumptions made during model design can perpetuate or exacerbate inequities, further disenfranchising marginalized groups.

Predictive policing is one area where algorithmic bias based on race can be a concern. Such risks are heightened further when there is no human participation in decision-making.

Unless there are clear accountability frameworks in place, the use of automated algorithms makes it challenging to assign responsibility when harmful or erroneous decisions are made, especially when AI is involved. Automated algorithms often operate as “black boxes”, making it difficult for individuals to understand how decisions are made. This lack of transparency and accountability can foster mistrust and skepticism about the fairness and accuracy of decisions taken.

In many cases, algorithmic bias can be the result of lack of knowledge, testing or sufficient oversight. How a model is developed, applied and governed is key to mitigating these risks. Independently of the input dataset used, the personal biases of individuals designing the assumptions of the model can also play a role in leading to unjust outcomes. These personal biases may be accidental (for example, the result of those inputting the data having insufficient technical expertise) or intentional, for example, to pursue political aims.

One risk that could come into focus more over the next two years is algorithmic bias against people’s political identity.58 Algorithmic political bias might be used intentionally to, for example, affect recruitment into public-sector jobs or access to certain public services or financial services. What makes this risk especially dangerous is that individuals’ political biases are widely known, and those biases can easily find their way into algorithms or data sets.

Furthermore, individuals’ political views can increasingly be determined, even against their will, from their online activities.

Similarly to individual biases, societal biases can also play a role.60 These are likely to become more prevalent as societal divisions deepen. In the GRPS, Societal polarization is ranked #4 over a two-year time horizon. Regionally, Latin America and the Caribbean, Eastern Asia and Europe manifest the most pressing concerns over Societal polarization in the next two years, according to the EOS.

Citizen surveillance risks

Government technology (GovTech) is entering a new era, as AI, data analytics and digital platforms become the backbone of public administration. Technology companies have long worked closely with governments, for example, in the sensitive Defense and Intelligence sectors. More recently, a broader range of government services, including other sensitive domains such as taxation, environmental protection, and voter verification and registration, have also become increasingly technology-dependent. Governments now have unprecedented access to data on citizens – and technology companies often have even better access than the governments themselves do. As the computing power available to governments and technology companies continues to rise, it becomes easier for both entities to monitor citizens’ activities.

When managed responsibly, analysis and processing of citizen data enables governments and the technology companies with whom they work to enhance public services. This can remain beneficial for citizens if effective legal guardrails are in place and both governments and technology providers act in ways that earn trust. However, without these conditions, the risks of misuse of surveillance capabilities rise.

There is divergence worldwide around how governments can use the data that they can access, reflecting ideology and culture, as well as the technological capacity and resources available to each government. Regulations, such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) also play a role, aiming to enhance personal data protection by placing stricter limits on data usage by governments and businesses.

Meanwhile, citizens often remain unaware of how their personal data is collected, used and shared, limiting their ability to make informed decisions. Figure 1.24 shows the close connectivity between Censorship and surveillance, Societal polarization, Misinformation and disinformation and Online harms, highlighting the confluence of these risks in the digital ecosystem.

Censorship and surveillance ranks #16 in the GRPS risk ranking on a two-year outlook, increasing five positions since last year, showing that concern respondents have around this issue is real and growing. In a world of deepening societal and political divisions, amplified by eroding trust in the digital environment, concerns with Censorship and surveillance are most pronounced in Eastern Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Central Asia, according to the EOS (Figure 1.25). Notably, Nicaragua ranks this risk as the fourth- most severe threat over the next two years, while eight other economies identify it among their top 15 risks.

Actions for today

Expand upskilling for people building and using automated algorithms Organizations should use AI models that minimize bias and mitigate unintended consequences in content creation and distribution. While technical solutions for significantly debiasing automated algorithms already exist, their consistent application remains a challenge. If implemented correctly, these solutions could greatly reduce the risks associated with model bias. Common debiasing strategies include data pre-processing before training a model, in-processing techniques during training, and post-processing steps after training. These methods help ensure that AI models are fairer and more equitable.

However, due to the rapid pace of change in AI development and the increasing complexity of its applications, keeping up with the latest advancements in algorithmic debiasing is difficult for many involved in building and using automated algorithms. To address this, there is a pressing need for continuous upskilling of developers, data scientists and policy-makers. Governments, civil society and academia should collaborate to create comprehensive training programmes that are frequent, regular, and reflect the latest advancements in AI and algorithmic fairness. These programmes should focus not only on technical skills but also emphasize the importance of ethical decision- making, responsible data-handling, and the societal impact of AI systems.

B. Boost funding for digital literacy

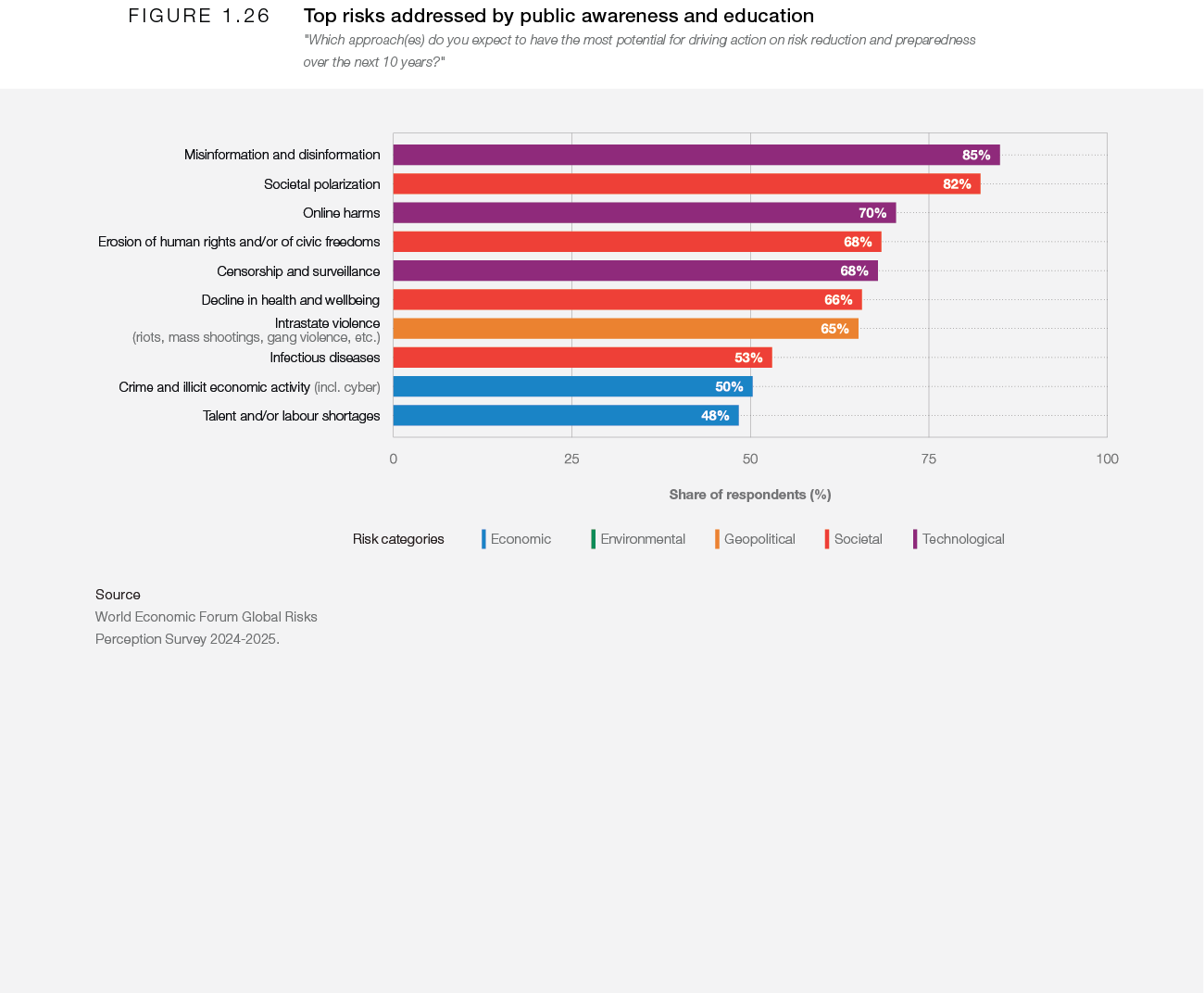

The GRPS finds that Misinformation and disinformation and Societal polarization are the two risks for which Public awareness and education has the most long-term potential for driving action on risk reduction and preparedness (Figure 1.26). Censorship and surveillance is also within the top five risks that could be addressed in this way. There is an urgent need for comprehensive public awareness campaigns to educate citizens about the risks associated with digital spaces, as well as the tools and practices they can use to protect themselves and boost trust in their use of platforms. For example, citizens should be educated on privacy and security settings for their devices, including two-factor authentication, and app permissions. Awareness programmes should also cover recognizing phishing attempts, protecting personal data, and securely navigating social media. Additionally, digital literacy initiatives should help individuals understand the role of algorithms and data in shaping their online experiences, fostering critical thinking to identify and challenge biased or harmful content. Governments, civil society and private-sector organizations all have a role in promoting these campaigns, ensuring they are accessible to diverse populations.

C. Improve accountability and transparency frameworks

The World Economic Forum’s Digital Trust Framework68 spells out key governance themes for ensuring AI’s sustainable and responsible adoption. They include accountability and transparency.

The former could involve establishing supervisory boards and AI councils, as well as human oversight processes. These committees should consider diverse perspectives from technologists, ethicists, legal experts, creators and others to effectively assess GenAI products and features. They should be responsible for reviewing AI practices, identifying potential risks and ensuring compliance with both internal policies and external regulations.

Regarding transparency, nurturing consumers’ trust requires organizations to inform about AI- generated content and its use through appropriate labelling and disclosures. Information on related data practices, safety policies and potential risks (such as bias and privacy) of the AI model used

in GenAI products should be made available via accessible documentation. Standards and technical solutions to ensure content authenticity – such as digital watermarking, content origin and history, and blockchain-based rights management – are currently under development to support a trustworthy information ecosystem. However, successful adoption at scale requires policy frameworks that are aligned with common principles, rules and technological standards.