Is Europe investing enough in research?

The dangerous cocktail in many European countries of high debt and subdued growth calls for smart fiscal consolidation. Cost-cutting programmes should minimize the potentially-negative short-term effect on economic activity, while establishing a foundation for long-term growth, with growth-enhancing public expenditure safeguarded from cuts or even increased (Teulings 2012).

An area often highlighted as needing protection in the context of shrinking overall public budgets is research and innovation (R&I). To examine how public expenditure on R&I fared in Europe during the crisis (i.e. since 2007), in Veugelers (2014) we look at the GBAORD (government budget appropriations or outlays for research and development) data.

On average, there is no strong evidence that EU countries sacrificed their R&I budgets more than other government expenditure during the crisis. However, while R&I investments were part of the stimulus packages at the onset of the crisis, more recently R&I spending has started to trend downwards.

Figure 1. Trend in government expenditures on R&D in the EU 2007-2012 (GBOARD)

Source: Veugelers (2014) on the basis of Eurostat and Ameco.

The average EU trend masks, however, an increasing divide among EU countries. To further explore this country heterogeneity, we distinguish innovation leaders (Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden and the UK), innovation followers (Austria, France, Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) and the rest (innovation laggards). We also distinguish high fiscal consolidation countries (Bulgaria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and Spain) versus the rest (low fiscal consolidation).

Figure 1 shows that innovation leaders increased public expenditure on R&I during the crisis by more than their increase in other public expenditure. Innovation followers reduced their public R&I expenditure more than other categories of public expenditure. Innovation laggards – including Italy and Spain – substantially cut public R&I expenditure, even more so than other parts of their budgets, resulting in a considerable drop in the share of R&I in public expenditure, which was already below the EU average. Most innovation laggards, perhaps not by coincidence, are also under greater fiscal consolidation pressure. Countries under high fiscal consolidation pressure have significantly cut their public R&I expenditure.

The crisis seems therefore to have widened the gap in public R&I expenditure between EU countries.

Public budgetary support for business R&I includes direct support through grants but also indirect support –predominantly through tax incentives. This indirect support is not visible in the GBAORD data. Tax incentives have become the main channel of government support for business R&I in countries such as Belgium, France, Ireland and the Netherlands. In all of these countries, use of tax credits increased much faster than grants during the crisis.

The increasing shift towards tax credits during the crisis is unsurprising given that tax credits for R&I are an easier-to-use instrument in times of fiscal consolidation. However, there is no strong evidence that tax credits are a more effective instrument for boosting private R&I compared to grants (see Veugelers 2014 for more on this).

European Commission policy on public R&I in a time of fiscal consolidation

How has the EU treated public R&I during the crisis, both through its own EU budget (structural funds and research funds), and its monitoring of member state R&I budgets and policies through the European Semester?

EU own R&I budget spending

The major sources of EU R&I funding are the structural funds (from 2007-13, about a quarter of structural funds went to R&I) and the Framework Programme research funding/Horizon 2020. This funding complements member states’ own public investment in R&I. In some countries, structural funds for research and innovation are of the same magnitude as national R&I budgets.

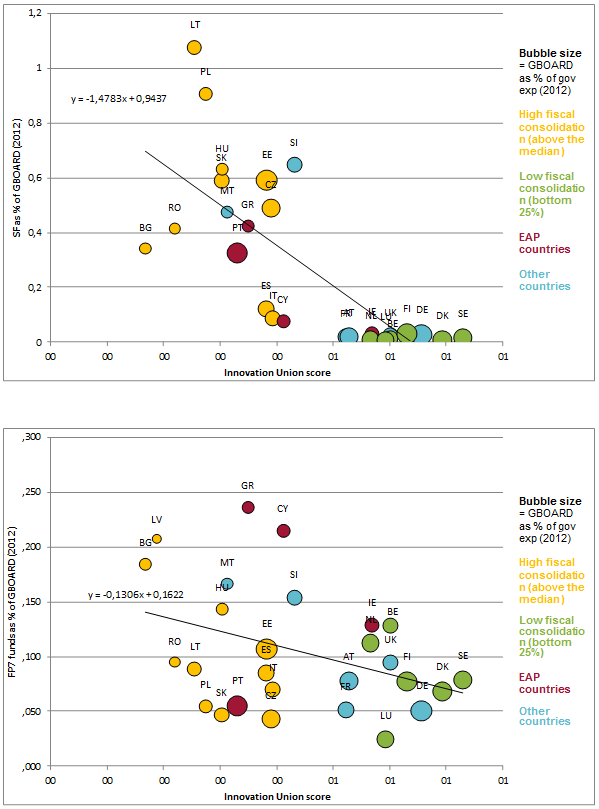

Figure 2. EU research and innovation funds and Innovation Union scoring

Note: EU funds are both the structural RTDI funds (left panel) as well as the FP7 funds (right panel). Latvia is excluded as an extreme outlier in the left panel

Source: Bruegel calculations on the basis of IUC 2007, Eurostat and AMECO.

The EU budget serves as mechanism to somewhat ease the growing public R&I divide in Europe. EU funds are relatively more significant for innovation-lagging countries with low national R&I budgets. Figure 2 illustrates clearly the negative relationship between EU funds as a share of national R&I spending and countries’ innovation scores. This is particularly evident for the structural funds. But it also holds, albeit to a lesser degree, for research funds allocated through FP7 excellence-based competitions.

EU funding in countries with declining R&I spends is likely to become even more important in future. With Horizon 2020, EU funding for R&I will amount to €80 billion, an increase of 30% compared to its predecessor (2007-13). In addition, a greater share of the structural funds is earmarked to be spent on Europe 2020 challenges during 2014-20 – from 50 to 80%.

Country-specific recommendations for R&I in the European Semester

The European Commission monitors the progress of member states towards their own R&I targets in pursuit of the Europe 2020 goals through the European Semester. An analysis of the Commission’s latest country-specific recommendations (Veugelers 2014) shows that recommendations related to R&I are patchy. The recommendations are not supported by the systematic use of evaluation tools to assess the impact on long-term growth.

The ‘investment clause’ use for public R&I budgets

A further means by which the Commission could promote R&I investment during crisis as part of smart fiscal consolidation is through the so-called ‘investment clause’. This allows member states that are in deep recession but that have budget deficits below the 3% of GDP threshold and that respect the public debt reduction rule, to temporarily deviate from the fiscal targets of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), to the extent of their national co-funding of EU-funded investments. The Commission proposed this in summer 2013 in response to the request of the European Council (2013). The investment clause, which extends beyond R&I, has however so far not been activated (Barbiero and Darvas 2014).

Are EU public R&I budgets being consolidated smartly?

The critical question that still needs to be addressed is whether the diverging trends on public R&I are good or bad news. Are the cuts in the weaker countries evidence of smart use of public R&I investment, i.e. were they effective in supporting recovery and growth and in eliminating inefficiently-spent public resources? Or have the public R&I cuts been too aggressive, jeopardising long-term growth? Is the Commission right to not allow members states in weak fiscal positions, which also happen to be weak innovators, to shelter their public R&D budgets from fiscal exigencies? Or should the Commission be more lenient and exercise the investment clause option?

Answering these questions requires an assessment of the long-term impact of public R&D on growth with the appropriate methodologies to evaluate causal effects. Although the number of studies evaluating public R&I programmes have grown substantially, they are still grappling with the causal link between public intervention and its impact on growth, and establishing proper counterfactuals to assess what the outcome would have been for the beneficiaries had they not received the support.

In addition, most evaluation studies only look at the immediate impact of public support on private research and development and innovation, checking whether it crowds out or generates additional private investment (the so- called ‘additionality’). There are few assessment exercises that pin down the longer-term social returns and growth impact of R&I, which is the impact that matters for smart fiscal consolidation.

Assessing social returns and the growth impact is a much more complex exercise requiring an integration of micro-additionality exercises into macro-growth-models. Such an integrated approach will allow an assessment of the complementary framework conditions needed to realise the growth dividend from public R&I and when needed, to identify which structural reforms (in product markets, labour markets, financial markets) are needed to generate innovation-based endogenous growth. An advantage of deploying integrated macro-models at the EU level compared to a country-by-country approach is that the EU scale allows assessment of the cross-country spillovers from national R&I policies.

Only when member states’ public R&I plans are properly assessed for their growth impact in an integrated framework, will we be able to conclude if the growing EU public R&I divide is a good or a bad trend.

Published in collaboration with VoxEU.

Author: Reinhilde Veugelers, Professor of Managerial Economics, Strategy and Innovation at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and CEPR Research Fellow

Image: A scientist prepares protein samples for analysis in a lab at the Institute of Cancer Research in Sutton. REUTERS/Stefan Wermuth

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Hyperconnectivity

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Financial and Monetary SystemsSee all

Jaime Magyera

November 13, 2025