Why the oil price drop matters

Michael A. Levi

Director, Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies, Council on Foreign RelationsAfter three years of unusual stability around $100 a barrel, oil prices fell steeply in the second half of 2014, dropping from $115 a barrel in June to around $60 by December. With oil critical to national economies, international security and climate change, what does the apparent new world of oil mean?

Less is known about where oil prices are heading than confident forecasters have suggested. Oil prices plunged in 2014 despite only a small excess of world supply over demand. This is a reminder that Saudi Arabia no longer plays the same stabilizing role in oil markets that it once did. (Contrary to many headlines, this is not new: it has been the case for at least the last decade.)

(This chart originally appeared on Vox)

But this feature of oil markets works just as well in the other direction: a gain in demand relative to supply could push prices back up to their previous level – or, if the boost is big enough, even above it. The return of volatility, not the fall in prices, is the trend that can most confidently be expected to persist. That said, with oil supply growth stronger than it was expected to be only a few years ago, and demand growth weaker, the world should anticipate lower oil prices than it would otherwise have seen.

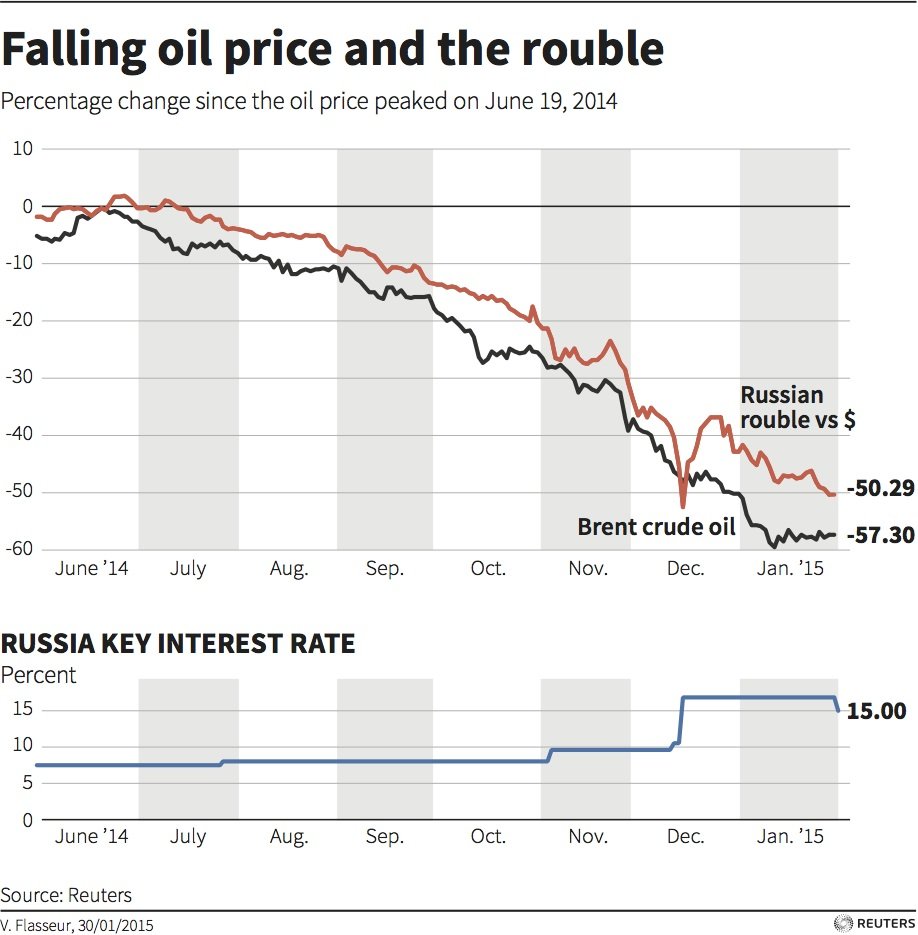

Oil price volatility is universally bad economic news. It stunts consumption and investment while often confounding economic policy-makers. When prices are falling, as they did in 2014, the biggest benefits accrue to major oil importers: even though US tight oil gets major credit for pushing prices down, the Chinese and European economies will reap bigger dividends. Among the G20 member states, only Russia and Saudi Arabia are clear losers (the Russian rouble, for instance, lost about 50% of its value vis-à-vis the major currencies in the second half of 2014), with Mexico and Brazil possibly ending up in that category too.

But the ultimate winners and losers will depend on how nimbly governments respond to changing oil prices. India, for example, has magnified its gains by using the opportunity created by falling prices to cut costly diesel subsidies – a move that has long been economically and strategically attractive but politically impossible. Brazil might yet reap a similar dividend if it uses the fall in prices to reform restrictive policies that have threatened to choke investment in its own oil resources. Russia finally has a chance to start to diversify its economy from the over-reliance on oil and gas. Decisions by consumers and producers will shape future oil production, consumption and trade, with economic and strategic consequences.

Beyond energy markets, lower prices – or at least periods of lower prices – impose pressure on Russia and Iran, two countries that have been at the centre of geopolitical storms. Both countries’ vulnerabilities can easily be overstated: with substantial cash reserves and some budgetary and exchange rate flexibility, neither is at significant risk of insolvency despite oil prices well below what the International Monetary Fund has estimated are necessary for their budgets to balance. And, for both, the geopolitical stakes involved in their ongoing conflicts are high, often outweighing economic concerns. But, all else being equal, falling oil prices might increase both countries’ incentives to eliminate other sources of economic pain – and, for both, that means using various tactics to ease geopolitical conflicts, but hardly throwing in the towel.

Amid all this, it is essential to remember that oil prices are not actually low. Even at $70 a barrel, oil prices are higher (in real terms) than in four out of five of the past 50 years and higher than they were 10 years ago. Much of the world’s oil-using infrastructure – automobiles, buildings, industrial facilities – was built when oil was much cheaper than 2014 lows. Compelling economic, strategic and environmental reasons remain to respond by reducing global oil use, even as prices decline.

The report, Geo-economics: Seven Challenges to Globalization, is available here.

Author: Michael A. Levi, David M. Rubenstein Senior Fellow, Energy, Environment and Director, Maurice R. Greenberg Center, Geoeconomic Studies, Council on Foreign Relations. Member of the World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council on Geo-economics.

Image: Valves and pipelines are seen at a gas compressor station on the Slovakia-Ukraine border in Velke Kapusany September 2, 2014. REUTERS/David W Cerny

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Oil and Gas

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Energy TransitionSee all

Roberto Bocca

November 17, 2025