Migration lessons for Europe from Australia

Stay up to date:

Humanitarian Action

One of the long-run consequences of the Arab Spring and the war in the Middle East is the mounting stream of migrants boarding boats in North Africa and making for Europe. In 2014, 170,000 were rescued and an estimated 3,419 died making this perilous crossing. This year the number is likely to be far greater. Not surprisingly, policymakers at the highest level have been urged to act.

In October 2013, the EU launched operation Mare Nostrum. Led by Italy, ships patrolled the Mediterranean to find and rescue migrants in rickety, overcrowded and sometimes sinking boats. In the face of criticism that this was simply encouraging more and more potential migrants to embark on the hazardous passage, the initiative was drastically scaled back a year later. But the momentum of migration continued to build, resulting in the current crisis.

In April 2015, EU ministers agreed on a ten-point plan and on 13 May, the Commission issued A European Agenda on Migration. This included measures to reinforce joint operations in the Mediterranean and (inspired by the success operation Atalanta against pirates off the coast of Somalia) to destroy migrant smuggler vessels. It included a range of other initiatives for cooperation within the EU on joint processing of asylum claims, and cooperation with source and transit countries on returning irregular migrants.

Dealing with migration: The case of Australia

What can research tell us about the dynamics of migration? One finding is that once migration streams get started, they cumulate through demonstration effects and through the professionalization of smuggling networks. Tougher policies can stem the flow, but only those that restrict access to the desired destination or deny the right to remain (Mueller 2014). Most migrants are willing to suffer all manner of hardships if they can ultimately gain permanent settlement at the destination. So, making life miserable for them, for example, by placing them in detention or denying access to social services, has little effect on the number that make the attempt (Hatton and Moloney 2015).

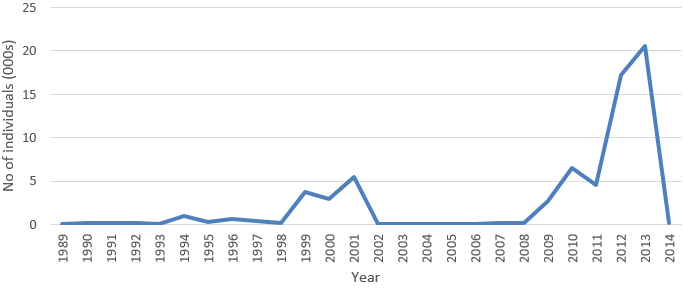

Australia provides an interesting case study. In the face of mounting boat arrivals, in 2001 the government introduced a range of measures such as excising outlying islands, and adopting a harsh offshore processing regime—the so-called pacific solution. The number of boats dwindled until a new government eased the policy in 2008. The number of boat arrivals then grew even more steeply than it had in the previous episode, to reach unprecedented levels by 2013 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Irregular boat arrivals to Australia, 1989-2013

Source: Phillips J. (2014)

In response, the earlier polices were reintroduced but with an even tougher edge. Offshore processing centres were reopened and those that had transited through Indonesia were denied the prospect of ever settling in Australia. Most controversially, Australian patrol ships were instructed to push back the boats. Where a boat was at risk of sinking, by default or design, the passengers were provided with a lifeboat and enough fuel to reach the Indonesian coast. These policies were stridently criticised as excessive and inhumane, even by those close to government. But the boats stopped.

How to deal with the Mediterranean situation

Could Australian-style policies be applied in the Mediterranean? The situation there is much more complicated; the numbers are much greater and North Africa is very close to Europe. Turning back boats would make a difference but it would be unlikely to stop the flow. And if lifeboats were provided to ferry migrants back to North Africa that would add to the already elastic supply of boats. Likewise, destroying boats in harbour and disrupting or disabling migrant smuggling networks would make a difference. But military strikes, as currently proposed, are likely to risk lives, and not just those of the smugglers.

Nevertheless, a combination of tough measures would go some way to stem the flow. And preventing people from drowning at sea is surely a good thing. But we should not lose sight of the fact that many of the migrants are genuine refugees seeking safety from persecution. Europe has been a safe haven for substantial numbers of refugees in the last two decades, and that humanitarian effort is widely supported. The gravity of the current crisis is such that asylum applications to EU countries in 2014 exceeded the previous peak of the early 2000s.

Since then, the EU has made strides in developing its Common European Asylum System (CEAS). This has included harmonisation of procedures to determine refugee status and cooperation on enhanced border controls. But, if anything, this process (which includes the Dublin regulation – that claims must be lodged in the state of first entry) has increased the existing mal-distribution across EU countries (Figure 2). A more even distribution would ease the pressure on ‘frontline’ states and there are arguments to suggest that it would increase total capacity (Hatton 2015).

Figure 2. Five-year total applications 2010-14, per 1000 population

Source: UNHCR, Asylum Trends (2014), Levels and Trends in Industrialized Countries.

A more even sharing of the ‘burden’ was envisaged in the Temporary Protection Directive of 2001, enacted in the wake of the Kosovo crisis. It was aimed at dealing with a sudden influx to one or more EU countries. But it lacked the teeth to impose a distribution, relying instead on voluntary pledges by other member states. Several proposals have been floated that offer formulae to distribute refugees between member states. But despite the establishment in 2010 of a central agency, the European Asylum Support Office (EASO), with a mandate to “facilitate, coordinate and strengthen practical cooperation among member states”, little progress has been made. Now the European Commission has proposed a distribution key but this has already come under fire from Britain and France.

An important question is where asylum claims should be processed. If the flow across the Mediterranean is successfully contained then some alternative mechanism must be provided through which asylum claims can be lodged. Providing such facilities in North Africa would provide a route for genuine refugees, which might relieve some of the pressure to board boats. It would also sift out economic migrants.

The current plan directs the European Asylum Support Office to deploy teams to Italy and Greece for joint processing of asylum claims. While the instigation of joint processing may be overdue, establishing enhanced facilities in Italy and Greece simply reinforces the incentive for potential asylum applicants to find boats, playing into the hands of the people smugglers that the strategy seeks to eradicate. Added to that, if unsuccessful applicants are not forcibly returned (as most are not) then the incentive for economic migrants remains.

Offshore processing has been mooted on previous occasions but it does not have a good reputation. The Australian centres on Nauru and Manus Island have only worsened it. Yet, there is a wealth of expertise to draw upon and well-managed, well-funded centres could do better. But there is a delicate balance to be struck between providing safe, clean facilities and avoiding creating a magnet such that the whole process would be quickly overwhelmed.

An even more difficult problem is how and where such centres could be established. The current plan is to set up a pilot multi-purpose centre in distant Niger. Self-contained centres with easy access to the Mediterranean coast might be less difficult to operate and involve less local engagement than trying to achieve ongoing cooperation with the authorities to destroy boats or chase down migrant smugglers. But that seems a far cry in the midst of marauding militias engaged in fluctuating power struggles in failed states such as Libya. Perhaps the best option would be to locate in more peaceful countries such as Tunisia. Alternatively, the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in Morocco might be good places to start.

None of this is easy. But people’s lives are at stake and thus difficult decisions need to be made. Decisive action needs to be taken, and soon. The EU and its member states have made some progress but they need to bite the bullet much harder than they have done so far.

References

Hatton. T J (2015) “Asylum Policy in the EU: The Case for Deeper Integration”, CESifo Economic Studies.

Hatton, T J and J Moloney (2015), “Determinants of Applications for Asylum: Modelling Asylum Claims by Origin and Destination”, ANU Research School of Economics Discussion Paper no. 625.

Mueller H F (2014), “Foreign intervention and the economic costs of conflict: A micro perspective”, VoxEU.org, 16 February.

Phillips J (2014) “Boat arrivals in Australia: A Quick Guide to the Statistics”, Australian Parliamentary Library.

This article is published in collaboration with VoxEU. Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Author: Tim Hatton is Professor of Economics at the University of Essex and at the Australian National University.

Image: A police officer checks a passport. REUTERS/Stefano Rellandini.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

Forum Stories newsletter

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

More on Economic GrowthSee all

Aengus Collins

May 14, 2025

Rya G. Kuewor

May 13, 2025

Tea Trumbic and Dhivya O’Connor

May 13, 2025

Navi Radjou

May 8, 2025

Dave Neiswander

April 28, 2025

Alem Tedeneke

April 25, 2025